By Dr. William Lawrence and Ms. Nicole Beres

The National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations visited the world renowned IDMAJ Foundation for Development in Casablanca, Morocco, in January, 2025. Then in June, we interviewed its founding director Boubker Mazoz. Founded nineteen years ago in the wake of the 2003 Casablanca bombings, IDMAJ is a growing set of youth and women community centers and training facilities along Morocco’s Atlantic coastline, located in disfavored urban areas. These inspirational centers are uplifting and transforming Morocco neighborhood by neighborhood.

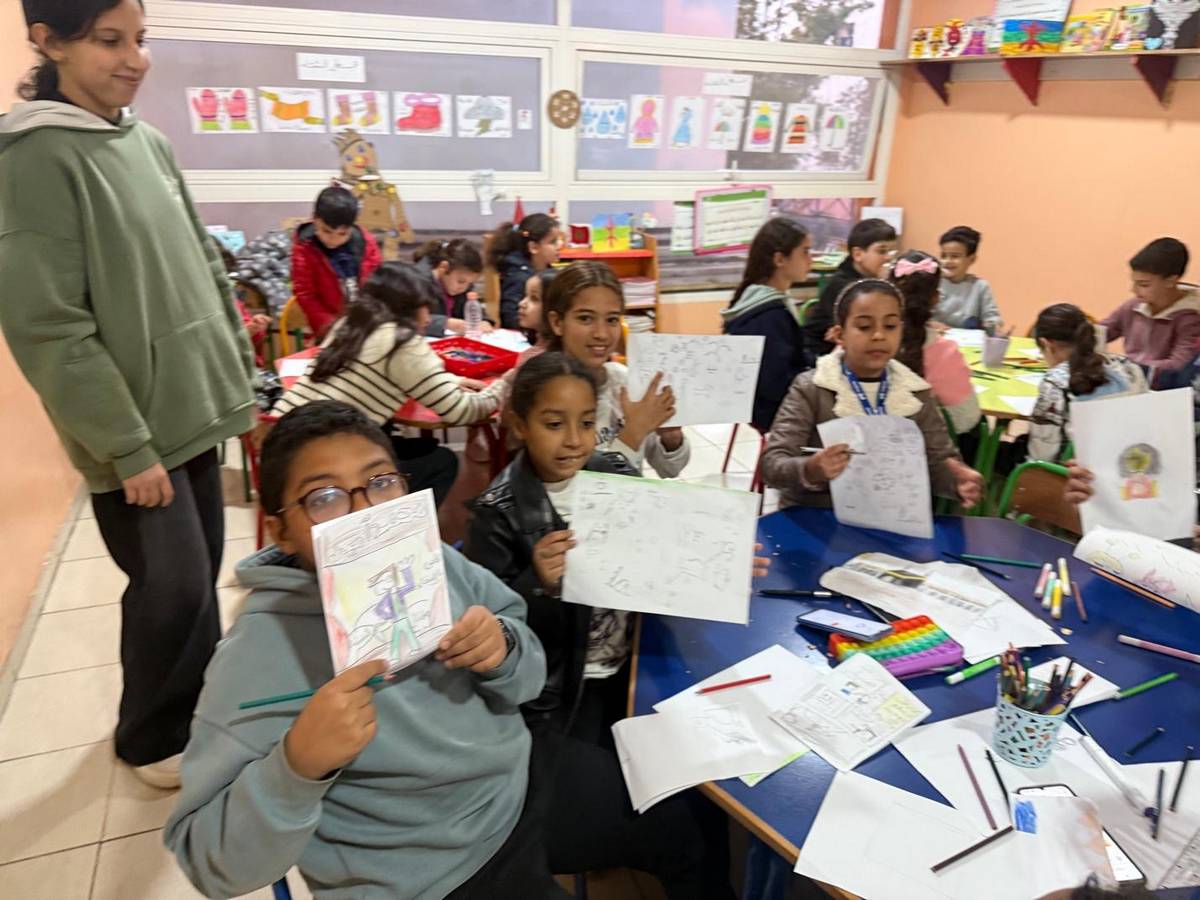

Upon arrival at one of the centers in January in Casablanca, the Council was welcomed by a powerful drum and dance performance by staff and participants in IDMAJ programs, followed by a comprehensive tour of two of the centers led by Mr. Mazoz. The Council delegation led by Board Chair John E. Pratt and Council President H. Delano Roosevelt also participated in a graduation ceremony, distributing diplomas to community members who had just completed a course of study in communications.

The IDMAJ foundation has transformed thousands of lives since its establishment in 2006 in the impoverished Casablanca neighborhood of Sidi Moumen. The first center was established in the aftermath of the 2003 terrorist attack, in which twelve suicide bombers attacked five locations, primarily Jewish sites, killing thirty-three people and injuring over a hundred. All twelve of the bombers were from Sidi Moumen, an area in Casablanca that, at that time, was home to over 350,000 residents living with limited running water and sewer systems. In 2006, the neighborhood of Sidi Moumen could be distinguished by heaps of rubble and corrugated metal roofs. Its residents were amongst the nearly five million Moroccans who were living in informal or low-quality housing at the time, almost a quarter of the country’s population, due in part to accelerated rural to urban migration to seek better jobs and services.

In response to the attacks, the first center was founded to protect the neighborhood’s youth from the social dangers that create a breeding ground for delinquency, violence, substance use, and extremism and to give a voice to the community of Sidi Moumen that felt disenfranchised and undermined by the neighborhood’s direct connection to the bombing. Three-quarters of Sidi Moumen was under twenty-five years old, and IDMAJ’s focus on youth would help heal and lift up the community it served.

Each center was co-founded and run by local youth and women dedicated to building community and fostering success. Almost two decades on, Sidi Moumen has produced a generation of leaders whose outcomes bear almost no resemblance to the urban poverty into which they were born. These dramatic transformations were paved in part by the IDMAJ Foundation for Development, which now boasts five centers with plans for more. IDMAJ, meaning “integration” in Arabic, helped pioneer social development through youth empowerment, women’s leadership, and changing marginalized neighborhoods from the inside out. These efforts run on the idea that an active and transformational community center in every less favored neighborhood in the world could effectively counter domestic and global turmoil.

In its 19 years, IDMAJ and its founder Boubker Mazoz have garnered recognition, accolades and numerous awards from many governments and international organizations, including major awards from the local and national authorities in Morocco and from the State Department and Sister Cities International, along with grants from the U.S. government, the National Basketball Association (NBA), the European Union, the IMF, and private donors like Volvo. His and his partners’ triumphs have been covered by many of the United States’ and the world’s major news agencies including NBC, ABC, the New York Times, and much of the Moroccan and regional press.

In describing the journey of establishing the Sidi Moumen Cultural Center, Mr. Mazoz illustrated how IDMAJ’s grassroots approach has been critical in achieving its objectives by first gaining the trust and engagement of the people the organization seeks to serve: “When we created [the community center], we were looking for the people of the slums.” Mr. Mazoz recalled entering poor neighborhoods, gathering together young people, and asking: “‘Did you see that building over there?’ ‘Yes, we saw it.’ ‘Well, why didn’t you come? That’s a Cultural Center and Community Center for you.’ ‘Oh, no, we don’t think it’s for us. It must be very expensive. It looks fancy.’”

Mr. Mazoz explained how the idea of volunteerism and community service was a foreign concept in a place that had been so long neglected. Traditionally, people in difficult circumstances in Morocco tend to rely on mosques for baseline levels of charity, and on extended family for other levels of support, if they have that option. There is a lot of horizontal wealth transfers in Morocco through families, more than in the United States, but it is not enough to transform neglected neighborhoods resulting from mass urban migration.

Marginalization in these neighborhoods, he says, ingrained a mentality in the people of the slums that “anything that is good, it’s not for them.” Thus, the IDMAJ initiative did not come without its doubters. However, on the same day that Mr. Mazoz and the students first entered the slums, they were able to bring forty families into the center. The community trust in IDMAJ has increased exponentially since then, winning over initial skeptics.

After the initial few years of focusing on young people, IDMAJ’s programs grew to benefit all members of society, particularly women. Mr. Mazoz recognized the need to develop programming for women when he noticed mothers sitting outside of the center while their children were inside learning, studying, and playing, and decided to “give them something to do” as well rather than wait idly. The Sidi Moumen Center started offering these mothers literacy courses and workshops on workforce participation, including sewing classes.

Mr. Mazoz emphasized the importance of creating a space for women, comparing the Sidi Moumen center to the Moroccan cafe, which is traditionally an environment exclusively for men. “In Morocco, women, especially traditional ones and conservative ones, don’t go to cafes or restaurants,” he explained. “So that was their cafe—where they come, where they learn, where they study, where they are being coached, and also where they can exchange their worries, their frustrations, their experiences, and we help them out to solve some of their family problems.”

Increasingly, women have been direct beneficiaries of IDMAJ training programs. The organization began sheltering women facing domestic violence and homelessness and providing counseling and therapy for victims of gender-based abuse. These “transitional spaces” help women heal from their hardships in a safe and supportive environment. Beyond initiatives serving battered women, IDMAJ also works to lift up women who are divorced, unemployed, or uneducated. The program “Ana Huna,” meaning “I’m here” in Arabic, works to empower women and help them achieve economic independence. This is one of IDMAJ’s many women-focused projects that teach financial literacy, organize cooperatives, and guide women in the creation of their own enterprises and the marketing of their products. IDMAJ is currently renovating their first center to transform it into the Center for Socioeconomic Integration of Women in Precarious Situations in Sidi Moumen.

IDMAJ has expanded geographically and is now working to keep youth off the streets and lift up communities in Ain Sebaa, Casablanca (2017), at a second Sidi Moumen center (2020), in Ibno Hanbal, Casablanca (2023), and in Tabriquet, Salé (2024, which opened while the Council was previously visiting IDMAJ in October 2024). The foundation is also endeavoring to build an additional center in Mediouna, Casablanca. The National Council also dined with the foundation’s local representative in rural Ifrane during its visit to the Middle Atlas Mountains later in February, who hopes to establish services in that area. IDMAJ is sending emissaries like him around Morocco to create plans for further expansion.

Reflecting on the successes of these centers, Mr. Mazoz points to both a positive impact on the communities and brighter futures for the individuals who participate in IDMAJ programming. The neighborhoods where cultural and community centers have been built have seen reductions in crime, “because those kids now have a place, they have a safe haven where they can go instead of being on the streets,” he explains. By promoting education and self-confidence, IDMAJ has helped these children achieve outcomes to which they otherwise would not have had access. Mr. Mazoz names specific examples of former students who have gone on to attend graduate schools abroad with international scholarships, become executive director of a gender equity organization in Canada, work for major companies in the United States, serve in the Moroccan police force and gendarmerie, and direct a language school. Perhaps the strongest testament to IDMAJ’s impact is that all of its employees are former beneficiaries, including youth who have returned after university, and mothers whose children used to attend the centers. This reinforces that idea that the inspiration that IDMAJ has instilled in communities motivates graduates to want to give back.

IDMAJ is continuing to expand its initiatives to lead youth towards entering the workforce and achieving a better life. “Especially now with the coming of the World Cup in Morocco, we are working on a big project to prepare people for hotel management, restaurants, and [language] interpretation,” Mr. Mazoz says. Programs like these are critical for Morocco’s development, as the country struggles with a relatively high youth unemployment rate of 22%.

Furthermore, IDMAJ’s efforts seek to encompass not just neighborhoods rife with urban poverty but rural areas as well, which suffer from significantly higher poverty rates and lower access to healthcare and education. The countryside projects began in response to the September 8th, 2023, earthquake, which directly affected over 600,000 people, killing 2,946 people and injuring or displacing tens of thousands more. “We had a very good experience in Al Haouz after the earthquake where we distributed over 120 goats to over fifty families, and we are still continuing that program,” says Mr. Mazoz. The organization assisted in distributing aid, created three cooperatives for women, and helped train fifty youth from the region’s villages in livestock care through a partnership with l’Institut de Formation aux Métiers de l’Elevage à Bellota (the Livestock Management Job Training Institute in Bellota). In Al Haouz, Mr. Mazoz sees rural challenges that IDMAJ could address, saying that “the kids have practically nothing, the school is too far, and the girls stop going to school after elementary school.”

To achieve these ambitions and all of IDMAJ’s goals, the foundation utilizes local and global partnerships and grants. “The challenge was always finances,” Mr. Mazoz says. “Looking for subsidies and for funds is always a big headache.” However, recent advancements will substantially boost IDMAJ’s resources and capacity. “For the first time we signed an agreement with two big institutions, CDG and the National Lottery, and we are going to sign, next week, a new partnership with Volvo,” Mr. Mazoz announced. Other key partners and sponsors—including the U.S.–Middle East Partnership Initiative and the consulates and embassies of the United States, France, the United Kingdom, and Australia—play a vital role in supporting IDMAJ’s work. In addition, volunteers from around the world, including the United States, come to Morocco in ever-increasing numbers and work alongside locals in supporting the various cultural and community centers.

These expansions are signs for optimism that IDMAJ’s concrete impact will continue to be as contagious as its founder’s aspirations and hope for Morocco’s future. “It’s always been my dream to have a community center in every [disadvantaged] neighborhood [in Morocco] and I think it is doable,” says Mr. Mazoz. IDMAJ’s story offers not just a compelling vision, but a tangible model of how locally driven initiatives can spark progress that reverberates far beyond the centers.

Works Consulted and Hyperlinked

- ABC News, ABC News Network, abcnews.go.com/Travel/chicago-students-learn-community-organizing-slums-casablanca/story?id=8809128. Accessed 13 June 2025.

“IV. Human Rights After the Casablanca Bombings.” Morocco: Human Rights at a Crossroads: IV. Human Rights After the Casablanca Bombings, www.hrw.org/reports/2004/morocco1004/4.htm. Accessed 12 June 2025. - “Gap between Urban and Rural Areas.” Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, www.bmz.de/en/countries/morocco/social-situation-169844. Accessed 12 June 2025.

- Kestler-D’Amours, Jillian. “Morocco’s Sidi Moumen Cultural Centre: Changing Futures and Perceptions.” The New Arab, www.newarab.com/features/moroccos-sidi-moumen-cultural-centre-changing-futures-and-perceptions. Accessed 12 June 2025.

- Mazoz, Boubker. Personal interview. 9 June 2025.

- “Morocco Earthquake 2023: Red Cross Response and Ongoing Aid.” British Red Cross, www.redcross.org.uk/stories/disasters-and-emergencies/world/morocco-earthquake-2023-latest-news-and-updates#:~:text=It’s%20estimated%20that%20600%2C000,overcrowding%2C%20and%20lack%20of%20sanitation. Accessed 12 June 2025.

- OECD. Revue de la politique urbaine nationale du Maroc. OECD Publishing, Sept. 2024, www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/09/revue-de-la-politique-urbaine-nationale-du-maroc_a9f1c7de/af7ee02f-en.pdf. Accessed 12 June 2025.

- O’Neill, Aaron. “Morocco – Youth Unemployment Rate 2005-2024.” Statista, 4 June 2025, www.statista.com/statistics/812261/youth-unemployment-rate-in-morocco/. Accessed 12 June 2025.