On December 10, 2010, at St. Margaret’s Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C., there was a memorial service commemorating the life of Eugene (“Gene”) Hall Bird. National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations Founding President and CEO Dr. John Duke Anthony was invited to attend the memorial service and, if possible, contribute a eulogistic note for remembrance. At the time, however, Dr. Anthony was in Saudi Arabia to attend the 40th Annual GCC Ministerial and Heads of State Summit and, thus, unable to attend the commemoration. He contributed the following for Gene’s family and friends as a remembrance.

But for my being abroad, nothing would have pleased me more than to be with the family and friends of the late Gene Bird at the commemoration of his life and legacy today. Many loved Gene and he loved them in return. The emotional connections that ensued were meaningful to both. In many cases, they enabled each to become someone different and better than they were before.

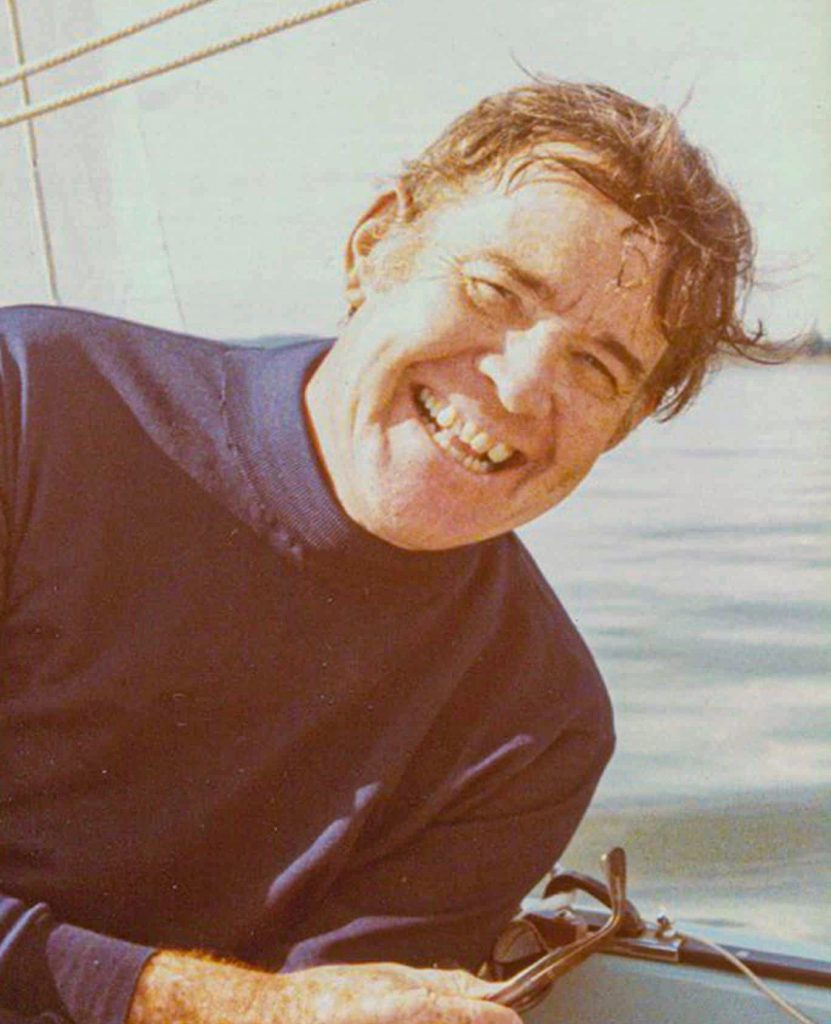

My memories of Gene are numerous and diverse. All are of warmth and companionship. These feelings accompanied Gene and those closest to him all his life. He was a man who raised the bar high. He often set and manifested standards of physical, political, and, above all, moral courage that few could match and none could surpass.

Many are the beneficiaries of Gene’s, Paul Findley’s, and others’ work with the Council for the National Interest (CNI). Gene would be proud, as are many, at how Philip Giraldi and others have carried on his spirit.

When Gene and others were in the earlier stages of building CNI’s presence and programming, what impressed me was how they went about doing something that no one had done before. He and his colleagues brought together a new constituency that some used to refer to as “graybeards.” The moniker was but a synonym for retired longtime specialists in the Arab region, the Middle East, and the Islamic world – one of the three or in some cases all of three.

In common to all three was that they found U.S. Mideast policies wanting and in too many cases devoid of the moral content that the U.S. officials so often preached to others. Not surprisingly, what Gene and his colleagues sought to grow was at once needed and effective. His was a major contribution that has endured.

Gene therefore put the lie to the adage that the only thing that a person can leave behind is their shadow. He left that, to be sure, but he also left something else: an ethically-focused institution that outlasted his life. His endeavors, and hence his legacy, have deepened and thickened the efforts of those whose ranks have never been huge but who nevertheless have always strived to be. Where others bothered not to tread, Gene not only did but led the way.

As such, Gene and others at CNI were trailblazers. Their work was devoid of cant. It was superior to what many, uncritically, regarded as informed opinion. Its commentary, in its wisdom, exceeded what too often passes for established thought. The crispness of its analysis leapfrogged over what to some was conventional wisdom.

For all this and more, many of us have long been in his debt – as we have remained in debt also and earlier to his beloved predeceased wife Jerri. Working with Israeli and Palestinian women victims of Israeli government oppression, she — Gene’s high school sweetheart and he hers — pioneered in working for peace and justice in Palestine. All of us who knew them well will forever regard Gene and Jerri in this way.

Even before Gene joined CNI, he knew of me as one of his fans. Now and then, our paths would cross somewhere in Arabia or the Gulf. Indeed, it was in Arabia that Gene left a little known but profound mark that has stood the passage of time and is hard to surpass. It has to do with what he did, but, unfortunately others who were in a similar position to do so did not. The reference is to the October 1973 Arab-Israeli war.

The record of what Gene did in regard to that catastrophic conflict can be found in the oral history that he contributed to The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. Former U.S. senior level diplomats interviewed Gene after he retired from his career as a U.S. Foreign Service Officer.

The remarks that can be accessed in Gene’s oral history contain a lesson. It is this. Had President Nixon been apprised of and acted proactively based on what Gene reported before the 1973 war, it is possible that the war could have been avoided. Had it been prevented, there would not have been the ensuing Arab oil embargo against the United States and other countries that were deemed unfairly and disproportionately supportive of Israel despite its treatment of Arab peoples. As would soon enough become apparent, the effects of the embargo would change profoundly and for far into the future the nature and dynamics of the international energy industry.

The context regarding Gene’s role was as follows. He was serving in the U.S. Embassy in Jeddah at the time. In the course of his duties, he met periodically with Saudi Arabia’s then Deputy Petroleum Minister, Prince Saud Al Faisal Al Saud. An extraordinarily rich part of Gene’s oral history is what Prince Saud and other Saudi Arabians told him, and Gene reported to his superiors at the Department of State, some months before the war.

Gene said that, earlier in 1973, the Saudi Arabians were told that Egyptian President Sadat had sent an emissary to meet with then-National Security Advisor and soon to be Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in Washington. According to Gene, Sadat’s emissary implored Kissinger to pressure the Israelis to withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula, which, seven years earlier, Israel had invaded and occupied in the June 1967 war. Only thus, Sadat reasoned, would Egypt be able to regain control of its Sinai oil and gas wells, which Israeli operatives were exploiting illegally.

More importantly, it would be necessary to bring about Israel’s withdrawal Israel’s from the Sinai in order to reopen the Suez Canal. The Egyptian government had been vitally dependent on the revenues from the Canal. However, it had been shut since the war, when Israel attacked Egypt.

Kissinger, according to Gene, and to the Egyptian president’s shock and dismay, refused outright to accommodate Sadat’s request. Not only that, but he taunted Sadat with the question, in effect, of, “What can you do about it?”

To the envoy, Kissinger’s remarks could be interpreted in only one way. To him and to the Saudi Arabians, who shared the information with Gene, who reported it to his superiors, the message was dire. The message was that the United States was not only going to do nothing to dislodge the Israelis from their ill-gotten gains at Egypt’s expense.

The message was also that, if Egypt wanted to regain what Israel had seized from it in the June 1967 war, it would have no choice but to launch a war with Israel. With the American diplomatic option thusly shut off, and with the United States leaving no other option on the table, this is exactly what Egypt did.

The moral of the story is that had Gene’s reporting been read and reported to President Nixon, and had Nixon, unlike Kissinger, moved to avoid the conflict, the war very likely would have been avoided. In time, doubtlessly numerous other scholars will read Gene’s oral history. If they do, they will also be as impressed and inspired, as this writer was and has been to this day, to learn not only who Gene Bird was but what he was.