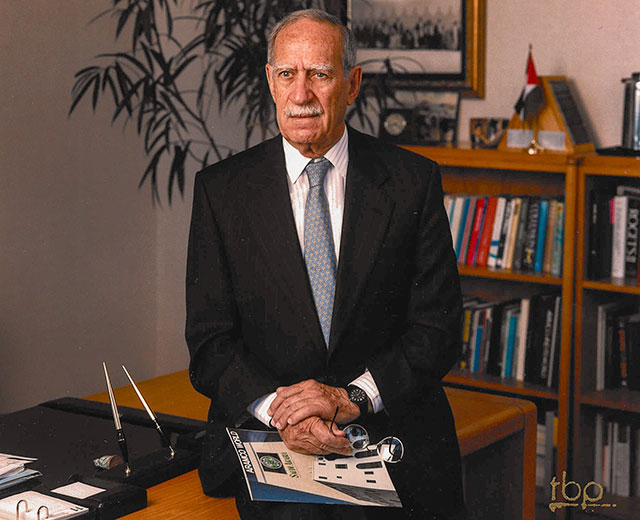

In the field of U.S.-Arab relations and much more, Shafiq Kombargi was an extraordinary individual. He was not just my friend. He was the friend of untold numbers of others. Those who loved and admired the man were countless. His passing brings a moment of great sadness.

Numerous specialists in the Arab region and U.S.-Arab affairs never met Shafiq, and some may not even have heard of him. Yet few individuals can match the outsized positive and enduring influence that Shafiq had on so many people’s lives.

The evidence is abundant. Shafiq’s sustained imprint upon innumerable United States-affiliated educational and cross-cultural institutions is massive.

Reaching Out to Others

Shafiq’s contributions were not those of a renowned researcher, scholar, university professor, or publicist. He was none of those. Yet all who labor in one or more of those fields have long been in his debt.

Shafiq’s gifts to Arab-U.S. cooperation and cross-cultural understanding were mostly made indirectly. In various instances, his accomplishments were achieved through and apart from his decades-long career with what was originally known as the Arabian American Oil Company, which in time became Saudi Aramco, and that, to this day, operates a subsidiary entity in the United States known as Aramco Services Company. Indeed, these entities had Shafiq’s back.

Often, Shafiq’s contributions were made from behind the scenes. Reduced to a single word, he was an enabler. Certainly, in addition to the example he set in other areas of endeavor, that’s how he influenced my life; doubtless, others can say the same.

To my knowledge, the more than a dozen institutions focused on the Arab region and U.S.-Arab relations that Shafiq had a hand in strengthening and improving include (in alphabetical order): • the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC); • the Arab American Institute (AAI); • American Near East Refugee Aid (ANERA); • America-Mideast Educational and Training Services (AMIDEAST); • the American University of Beirut (AUB); • the American University in Cairo (AUC); • the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies (CCAS) at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service; • the Center for Middle Eastern Studies at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS); • the Jerusalem Fund; • the Journal of Palestine Studies (JPS); • the Middle East Institute (MEI); • the Middle East Policy Council (MEPC); • and the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations (National Council).

Shafiq’s contributions were often inextricably associated with how he helped strengthen other organizations’ educational programs, projects, events, and activities. The ones listed herein and more were, in turn, linked to the quality of people’s lives and minds, especially with regard to knowledge and understanding of other peoples and cultures.

To their credit, none of these entities that benefitted from Shafiq’s and his colleagues’ assistance were able to do so simply because they submitted a request. Quite the contrary. Rather, they were rewarded as a result of Shafiq and his associates having closely examined the nature of their work, determined the extent to which it was relevant, and weighed the extent of their effectiveness in terms of whether they were making a difference.

Literature and Leadership

Take, for one minor example, Shafiq’s association with Aramco’s flagship publication, AramcoWorld. No other publication has elucidated so consistently and effectively the contributions of Arabs and Muslims to the world’s civilizations and humanity in general. In the span and depth of its cultural, historical, and geographic reach, in the quality of its photography, artwork, and other illustrative material, and in the prodigious diligence behind the selection of each issue’s contributors, AramcoWorld‘s appeal to sheer intellectual curiosity, aesthetic taste, and academic interest reflects Shafiq’s laudable objectives, good judgment, and consistent striving for the highest standards.

Again, in these and other ways, Shafiq was a bridge builder. As such, he was extraordinary in the way he helped to further the educational initiatives of the National Council, where it has been my privilege and honor to serve as Founding President and CEO since the Council was established in 1983. One program he supported was the Council’s flagship Youth Leadership Development Program, the Model Arab League. This program occurs 24 times a year in more than 20 American cities and four Arab countries. To date, it has produced more than 49,000 graduates.

Among them are numerous American diplomats, Congressional staff, and other foreign affairs practitioners. In Egypt’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs alone, more than a dozen Ambassadors are graduates of this program. In another instance, the current editor of AramcoWorld, Richard Doughty, a graduate of the internationally-renowned Missouri School of Journalism, began his career in Arab affairs as an intern at a magazine in Cairo, Egypt, through the National Council’s Joe Alex Morris Jr. Arab World Journalism Scholarship, which Shafiq indirectly also supported.

In innumerable microcosmic ways, Shafiq bequeathed Americans and the citizens of other countries enhanced cross-cultural connections and new lenses through which to view the Arab and Islamic regions and beyond. The National Council was just one of the many beneficiaries of what Shafiq promoted. If one were to multiply each particular instance with the effect on the institutions he assisted, only then might one begin to grasp the truly prodigious and long-lasting results of what the man left behind.

The Intangibles

Yet this rudimentary effort to calculate the nature and meaning of Shafiq’s professional life has its limitations. Indeed, any attempt to assess and evaluate even a small portion of someone’s time on earth risks being misleading. For instance, it does not come close to defining what is at once far dearer and more elusive of description about the man. This other, more intangible gift which Shafiq shared with so many was an example of how to live with purpose and principle.

Not only did Shafiq possess a basic and pervasive decency. He was heartfelt and sincere. When he was with someone he liked or admired, he was the greatest of listeners. He was never one to look around or over one’s shoulder to see whether someone more important or interesting was in the room.

Shafiq had a gift for those he cared about and who he knew cared about him. This was his always leaving them with the feeling that he was concerned about no one else. This aspect of Shafiq’s innate warmth and kindness produced an indelibly positive and enduring imprint upon those who knew him.

In saying such things, it is tempting to speculate about the sources of Shafiq’s sincerity and gentleness of spirit. It may be a stretch, but perhaps an explanation lay in the circumstances surrounding the formative and most important influences upon his upbringing.

The Nakbah (The Catastrophe)

Shafiq spent his childhood in Palestine. His was a family of well-established shipping agents in Jaffa and Haifa. This was before his and other Arab Christian and Muslim Levantine families’ hearts and souls were smashed to smithereens by usurpers of their land and resources. Shafiq’s family lost their homes and businesses in the ethnic cleansing by Jewish militias that eventually became the Israel Defense Forces. While fleeing, Shafiq saw one of his friends killed.

Perhaps a psychologist could better explain how suffering such a tragedy might impact someone. As to what affected Shafiq the most, it is possible that it could have been the immense emotional wound inflicted upon him and so many of his fellow Palestinians. Perhaps it was this, which he witnessed and experienced for himself and others firsthand, that drove him to work to enhance links between the Eastern Mediterranean and Arabia and the Gulf, and between the United States and the Arab region. Through his promotion of understanding, others could become acquainted with the realities of what happened to Shafiq’s family and community.

Evaluating a Legacy

Measuring anyone’s life is not an easy task. For many Arabs of the east, however, there is a threefold framework for evaluating a person’s legacy. It consists of weighing how well the deceased treated their family, what they set aside to assist them in the future, and a net assessment of the quality of their life.

The last criterion considers whether a person was one of rectitude, and, if so, to what extent. Did they exemplify one or more forms of courage? Did they exude compassion for the less fortunate? Were their personal and societal values and commitments based upon ethical precepts and, in particular, an abiding concept of justice? A distinctive feature of Shafiq was that he excelled in all of these areas of measurement.

In remembering and paying homage to the memory of Shafiq, all who were privileged to know him will acknowledge that his role and record of selfless service to others will long stand as a model.

Among Shafiq’s many fine attributes was his ability to simultaneously combine decency and integrity. What is more, one could search high and low and not find anyone to match Shafiq’s gracious demeanor, record of charity, and exemplary approach to public service.

In honoring Shafiq, all of us will remain indebted to him for what he did to help increase knowledge and understanding of the Arab region and its peoples, and about Arabs across the board – that and for his demonstrating what a life of dignity and inspiration is all about, and to ourselves and others, what such a life can be.