That the foreign policies of various governments often appear to be confusing or contradictory is because they frequently are. During Barack Obama’s presidency, such inconsistency has seemed to characterize aspects of America’s relations with the six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. The ambiguity and uncertainty that accompanies it is among the things that Obama has sought to dispel and clarify in the course successively of his March 2014 visit to Saudi Arabia, his May 2015 summit at Camp David with senior leaders of all six GCC countries, and his mid-April 2016 attendance at a similar meeting with leaders of the same countries. As this essay seeks to demonstrate, what he has had to contend with – and what others of late have had to contend with regarding aspects of his administration — in terms of background, context, and perspective has not been easy of resolution, amelioration, or even abatement.

Assumptions, Ambitions, and Abilities

Dating from before and since these high-level GCC-U.S. meetings, Washington has taken steps to strengthen and extend America’s overall position and influence in the GCC region. A principal means for doing so has been through the GCC-U.S. Strategic Dialogue.[1] But one example among several was when former Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel, along with Secretary of State John Kerry, came with approvals for billions of dollars in sales of U.S.-manufactured defense and security structures, systems, technology, and arms to GCC countries, together with long-term munitions and maintenance contracts.

Yet, simultaneously, signals from Washington and the mainstream U.S. media before and since Obama’s meetings with his GCC counterparts have not always been as clear as the signalers thought would or should be the case. That said, what specialists have had no doubt about for some time is that the Obama administration is recalibrating the strategic focus of its international priorities in hopes of being able to accomplish two objectives at the same time. One objective has been, and continues to be, a steadfast resolve to remain committed to the security, stability, and prospects for prosperity in the GCC region. The other has been and remains a parallel determination to emphasize the Asia-Pacific regions.

Affecting the need for such a recalibration have been major U.S. budget reductions and their impact on strategic concepts, forces, and operational dynamics. At issue and under examination in this regard, according to the Secretary of Defense in advance of the most recent Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR), are, and for the foreseeable future will continue to be, America’s assumptions, ambitions, and abilities.

Understandably, the GCC region’s reaction to these trends and indications was and continues to be mixed.

Positives of U.S. Policies

On the positive side, many among the region’s strategic analysts and policymakers have been and remain pleased with the continuing high-level of military, security, and intelligence cooperation between the United States and the GCC countries.[2] Others continue to appreciate not only that America’s forward deployed land, air, and naval forces have ensured the ongoing safety of the region’s oil exports. Equally appreciated has been how this assistance has contributed mightily to the preservation of the member-states’ national sovereignty, political independence, and territorial integrity. Moreover, all acknowledge that it is the United States that has contributed substantially to the region’s overall security, governmental stability, and, hence, to the degree of peace and prosperity that the vast majority of the GCC countries’ citizens have enjoyed for decades and that is unrivaled elsewhere in the Arab world.[3]

[pullquote]All acknowledge that it is the United States that has contributed substantially to the region’s overall security, governmental stability, and, hence, to the degree of peace and prosperity that the vast majority of the GCC countries’ citizens have enjoyed for decades and that is unrivaled elsewhere in the Arab world.[/pullquote]Member-states have also been relieved that a robust U.S. diplomacy has averted an American and/or Israeli armed attack against Iran’s nuclear facilities. In this regard, they appreciate how such efforts have thus far prevented an international conflict that such an attack could provoke.[4]

Negatives of U.S. Policies

On the negative side, it is difficult to deny that not just the United States, but also America’s worldwide allies, and, most important, the Gulf countries themselves, have grown weary of wars in this region. Indicative of this reality is a palpable malaise among a core of U.S. strategic analysts. Among them are those that have come to perceive Washington’s relations with Arab and Islamic countries as a perennially exhausting enterprise. Included in this group are those that believe the nature and extent of the relationship for the past three decades has been unceasingly difficult to manage and sustain.[5]

Others echo such sentiments. They maintain that economically, financially, politically, and otherwise, the United States is less and less in a condition or mood to prolong what, in the eyes of many, have been associated with the violent attacks against the United States on September 11, 2001, by Arabs and Muslims. In this regard, growing numbers of Americans believe it unnecessary, if not reckless and foolhardy, for the United States to be expected to continue with business as before. More specifically, many are no longer as inclined to expend the extraordinary amount of time, effort, and resources, unaided by others, to protect American and allied interests in these regions to anywhere near the extent of protection that went largely unquestioned in years past.

From another perspective, just as many, if not more, chafe and remain disappointed at the continued unwillingness of the United States, in concert with Saudi Arabia and other GCC countries, to do whatever is necessary to bring down the Syrian regime.[6] Only thus, many contend, could one expect to weaken Iran’s ability to meddle in the domestic affairs of GCC and other Arab countries. More specifically, only thus also would Tehran likely be deterred from fomenting and sustaining the civil strife in Iraq and the domestic dissension in Bahrain, other GCC countries, and beyond and continuing to support the Lebanese Hizbollah.

Additional GCC dismay was rooted in two other developments. One was the Obama administration’s change of plans regarding whether to bomb Syria. The second was Washington officialdom’s perceived backtracking and flip-flopping in its actions toward Egypt, given that the Mubarak regime had been a stalwart American ally for 30 years.[7]

Bahrain: Long an Outsize Position and Role

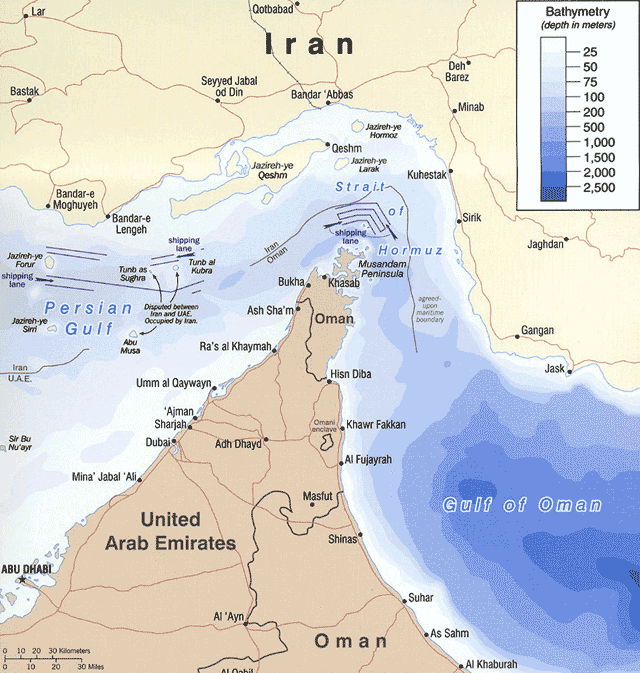

In these regards, no one should doubt the pan-GCC opposition to the Islamic Republic’s longstanding designs on and history of intrusion into the domestic affairs of Bahrain.[8] Though small in size and population, Bahrain, owing to its having hosted an American naval presence since the late 1940s, has long played, and would likely seem destined to continue to play, an outsize role in the safe flow of Gulf energy sources through the Hormuz Strait.

Less well known, but equally if not more important from the perspective of GCC nationals, is the other side of the coin. The reference is to a similar key role that the Bahrain-based U.S. naval presence has long played, namely to assure that the region’s vast supply of unfettered imports reach local markets through the same waterway.

The American land-based naval forces within the GCC region and nearby areas therefore remain vital to more than Bahrain, where they are home-ported. Indeed, they remain essential to the economic, social, political, and governmental security and stability of the Gulf as a whole as well as the entire eastern Arabian littoral from Kuwait to Oman.

Concerns Regarding Iran and Lebanon’s Hizbollah

As for Hizbollah, many American and Allied prominent intelligence analysts depict it as practically a wholly-owned subsidiary of Iran. In this regard, there seems little if any reason to assume that GCC observers’ concerns about the Lebanon-based organization have been inaccurately based. Members of the party’s worldwide networks have been and remain organized, trained, disciplined, and capable, with some ready at a moment’s notice to strike anywhere to create crises and wreak havoc the world can ill afford to suffer.[9]

Moreover, it is well known among specialists that Hizbollah activists have provided organizational, political, and training advice not just to members of the radical Ansar Allah, the so-called Houthis of Zaydi Shia religious persuasion in the north of Yemen, that have opposed the government of the last legitimate President of Yemen, Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi. Hizbollah has provided similar assistance to leaders among the Harika, the Republic of Yemen’s would-be secessionists, whose origins are the former Marxist-Leninist Democratic Republic of Yemen (also known as South Yemen) and whose members, albeit not known for emphasizing their religious identification in terms of their political goals, are nonetheless overwhelmingly Sunni in their theological orientation.

Embedded Echoes of an Earlier Error

Beyond the enumerated concerns, members of the GCC also remain resentful of the fact that the P5+1 – representing the five Permanent Members of the United Nations Security Council, i.e., China, France, Great Britain, Russia, and the United States, plus Germany – excluded them from the negotiations with Iran. That Washington proceeded in this manner, given that Iran for more than three decades has been the GCC members’ largest, far more populous, militarily stronger, and threatening neighbor, strained credulity.[10] The content of conversations that practically anyone had on this subject with political analysts in the GCC region was illustrative.

The Obama administration’s critics in the GCC countries have pointed out that this is as great an example as one could cite of an empathy deficit at the highest levels of the U.S. government for the legitimate needs, concerns, and interests of a group of America’s allies. Certainly, none with whom this writer discussed the matter could conceive of the United States being expected to accept and accommodate a comparable fait accompli were, say, China or Russia to enter into sensitive strategic security- or defense-related negotiations with Canada or Mexico in Ottawa, Mexico City, or elsewhere.

In GCC eyes, particularly irksome in this regard were aspects of Washington’s attitudes and behavior. If measured by the need for policymakers to be careful to say what they mean and mean what they say or imply, what the United States did was unconscionable. In what appears to have been with little thought to the consequences, the United States seemingly almost off-handedly opted to appease and accommodate Iran’s opposition to representatives of the GCC countries being allowed to be present in the meetings or attend if only as non-participant listener-auditors. The United States did this despite over three decades of Iran’s leaders having continued to refer to the United States as “the Great Satan” and also Washington officialdom itself long ago listing Iran as a state sponsor of terrorism.[11]

Together with regional analysts and representatives of private sector communities, these and other slights have been worrisome for numerous GCC analysts. They have caused some in the GCC region to wonder whether their governments might be next on the list of America’s partners whose leaders – in the manner of Iran’s Shah, the Philippines’ Ferdinand Marcos, Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, Iraq’s Saddam Hussein, and others – became disregarded and, ultimately, deemed dispensable. Those analysts and others who have wondered thusly can perhaps be forgiven for questioning whether America will stand by its longtime friends and strategic allies this time around. If so, they wonder whether such help as Washington officialdom might extend will prove to be effective or, as in other instances, too little and too late.

Continuing Doubts and Suspicions

Not least among numerous developments of the past few years that have fueled such concerns were reports in late June 2014 of how the United States and Iran might be on the verge of colluding in a matter of significant strategic import. The matter in question was whether Washington and Tehran might agree to coordinate their efforts — which in short order they did — on a matter of great sensitivity not just to Iraqis but also to Iraq’s neighbors. The issue was whether the United States and Iran would try to preserve the Shia-led Iraqi government in Baghdad, which the United States and the Islamic Republic had helped to install, lest it fall to the so-called Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (or ISIS) or other Sunnis led by former Ba‘thists and extremist insurgent offshoots of Al-Qaeda bent on its ouster.[12]

In the eyes of GCC leaders, whatever the strategic basis for Washington’s and Tehran’s connivance may or may not have been or may yet become, the effect of any perceived U.S.-Iranian unity of objectives in this or in other instances has been and is more than troublesome; to some, it has smacked of American policymakers’ callousness. To others, it has betrayed yet another instance of Washington, however inadvertent its intention, lending a de facto boost to Tehran’s regional standing and clout regarding a matter of grave importance to GCC country relations with Iraq and Iran.

Added to the negative interpretations and anxieties that have resulted is something else that, perceptually, is of related importance. There has been and continues to be ongoing suspicion among GCC analysts of an untimely and inordinate American intention to pivot from the GCC region toward not just Europe and Latin America, but also, and the more so, Asia.[13] However much they would have wished it were otherwise, numerous GCC intelligence and policy analysts have come to view the purported American geopolitical strategic shift as being, at a minimum, at least partially true.

Faits Accompli Run Amok?

Underscoring the pan-GCC consternation has been a matter of even deeper concern. It is the view that the U.S. decision to pivot, or “re-balance America’s global priorities,” a phrase that is sometimes used instead, if it is as true as many have indicated, was apparently arrived at unilaterally. Again, to the degree that what innumerable observers have written is accurate, this left many among the more ardent pro-American elites within the GCC region taken aback. In the interplay of action, reaction, and interaction of diplomacy, faits accompli regarding a matter as serious as this one would ordinarily be unacceptable. On either side of a special relationship and an unofficial, informal alliance, which is what the GCC-U.S. relationship has been since the day the GCC was established, such acts are supposed to be off-limits and unpardonable.

This was not the first time an American strategic partner has taken umbrage at Washington’s having failed to consult it ahead of time about a pending U.S. decision likely to affect their interests. Similar perceived American acts of unilateralism occurred in the 1950s with regard to unbridled U.S. support for populist national liberation movements in Arab North Africa seeking independence from French imperial rule.

Such American actions angered officials in Paris. They did not go unanswered. French President Charles de Gaulle responded in kind. In one reaction, he pronounced that France would henceforth reconsider its commitment to the military arm of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). In another, he deliberately failed to inform Washington in advance of his ordering the mobilization and deployment of French forces to join those of Britain and Israel in an invasion of Egypt, thereby precipitating the Western world’s gravest crisis since World War Two.

Unraveling the Existing International Order

What so many in the GCC found upsetting was not just the way in which the United States arrived at its decision. And it was not only the manner in which Washington issued the announcement and tried to explain it. More profoundly, it was the substantive dimension of Washington’s decision that especially riled GCC policy commentators who endeavored to fathom its implications.

Even the most clinical, objective, and dispassionate GCC analysts failed to reach a positive conclusion about the potential consequences. Instead, they perceived the matter in many ways with the same disbelief that they had perceived the American determination to invade Iraq. In that instance, what enraged Arabs the world over – and many throughout the planet — was the cavalier manner in which the United States attacked not just any Arab and Islamic country but one that, more than any other, represented historically the zenith of Arab culture and civilization. In itself, that was hardly a matter of small moment in the annals of the Arab-U.S. relationship.

[pullquote]Even the most clinical, objective, and dispassionate GCC analysts failed to reach a positive conclusion about the potential consequences of a U.S. strategic ‘pivot’ away from the GCC region. Instead, they perceived the matter in many ways with the same disbelief that they had perceived the American determination to invade Iraq.[/pullquote]What compounded the shock was that Iraq had not attacked the United States. Neither was it a serious, credible threat to important American national security, economic, or related interests. And adding insult to injury was that the George W. Bush administration proceeded to do so despite strong and repeated opposition by most of the GCC region’s most astute and seasoned specialists and foreign policy practitioners.

Courting Disaster

As remarked to me by the foreign ministers of two GCC countries, most of the GCC countries’ leaders advised the United States not to invade and occupy Iraq. Were it to do so, they said, it would not know what it would be getting into in the view of many of its closest friends who, from broad and long experience with Iraq and its people, knew better. It would quickly regret having done so. For certain, they emphasized, it would be courting disaster for itself and the Iraqi people. That Washington officialdom refused to heed the advice of its GCC allies, who were not only wiser with regard to Iraq but also had American, Iraqi, and their own interests at heart, is reckoned by many to have been one of the worst foreign blunders in America’s history.

As with the George W. Bush administration’s decision to effect regime change in Baghdad in 2003, more recent U.S. actions have seemed at once not only inopportune and unwarranted. Worse, in the eyes of some GCC observers, U.S. foreign policies have emboldened Iran’s leaders. Certainly, GCC leaders claim, by its policies and actions, the United States did little if anything to stop Iran from its continued meddling in Arab internal affairs.

Tehran’s arming, financing, and facilitating militias and other disgruntled groups seeking to destabilize and, where possible, supplant various Arab governments is of particular concern in this regard. Of equal if not greater concern, however, is one of the consequences: the process of upsetting if not overturning the existing international order. Little mind, America’s Arab, Asian, European, Latin American, and U.S. critics emphasize, that this is the same manner of objectionable international behavior that the United States, as much as if not more than any other country, set in motion with the George W. Bush administration’s policy of regime change.

But, “Ah,” the apologists for such a policy might say, “Yes, but the two cases are different. In this case, a country other than the United States is doing such things.” In any event, the order that Iran’s actions are eroding – and, in the case of Iraq, UN Secretary General Kofi Anan accused the United States of violating — is the global system of respect for the rule of law, order, and adherence to the inter-state, or international, system in play. The system has been the primary frame of reference for the interaction between countries since the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia, which established the current structure and system of international relations.[14] Still, none among the GCC’s foreign policy elite are naïve about how trends and indications in international affairs can produce, and have produced, shocking developments for which many, if not most, were poorly prepared. In this context, none have taken issue with the reality that there are moments in any country’s history, America’s included, that mandate a reassessment and realignment of its strategic international relationships, resource allocations, and foreign policy priorities.

Propellant Factors and Forces

Four phenomena, each one fueling the others, have fed GCC apprehensions about a United States strategic pivot away from the Gulf region. One is a consequence of the severe U.S. government budget cutbacks. A second is a growing concern expressed to me in August 2014 by two different American corporate representatives, who asked that their names be withheld as they were not authorized to speak for the record, about their respective apprehensions regarding China. They emphasized their belief that China is determined to position itself in order to be able eventually to mount a serious challenge to the United States’ hyper-power status globally, beginning in its own neighborhood of Asia. The implication was clear: anyone who didn’t adapt a more proactive policy to prepare for such an eventuality would be a fool.

A third phenomenon is the lure of Asia’s vastly greater consumer markets for U.S. exporters. With this, it is believed, would come the accompanying prospects for not only improving innumerable corporations’ profitability. Also likely would be the generation of thousands of American jobs. So, too, would there likely be significantly augmented flows of revenue into the U.S. Treasury and perceptually a corresponding enhanced capacity to, if not reduce, then at least slow the increase in American taxpayers’ levels of dependence upon China and other nations that own American national debt instruments.[15]

A fourth phenomenon is the impact on strategic thinking that derives from a looming specter of China, along with Russia, becoming world-class blue water oceanic powers to a far greater extent than previously.[16] Both countries are increasingly well positioned to expand their maritime trading routes. Their doing so, many believe, would be at America’s and other countries’ expense. In so doing, America’s global competitors would be validating the adage that time – and ideas perceived as potentially beneficial – waits for no one.

Indeed, China and Russia are already expanding their naval capacities and involvement not only in and through the Indian Ocean. They are doing so also via a heretofore inadequately charted area in a distant and different direction, one that is laced with innumerable uncertainties as well as potential opportunities for strategic advantage and economic gain. The region in question is the Arctic Circle, whose waters have become navigable to a greater extent than previously due to climate change.

Peripatetic Activism

Reflecting the push and pull of these four phenomena has been a steady progression of high-level Obama administration visits to the Asia-Pacific region.[17] Not surprisingly, the visits have been accompanied by declarations of ongoing U.S. support for key American and Asian foreign policy objectives. Such declarations are linked to two domestically rooted phenomena that are increasingly receiving serious and favorable consideration.

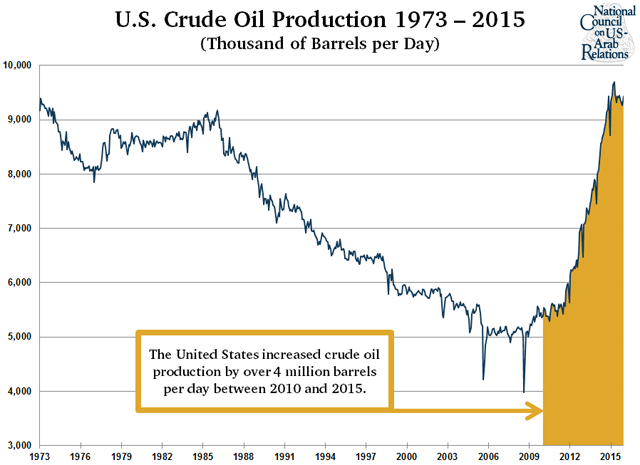

The first has to do with America’s oil and gas sectors. In recent years, these sectors have achieved record-high production levels. The second is linked to the first. It has to do with a greatly lessened likelihood of America remaining as dependent upon the Middle East’s hydrocarbon fuels to anywhere near the same extent as in the past.[18]

The two phenomena combined are being likened in the minds of domestic components of the U.S. body politic to a welcomed new strategic opportunity. While envisioned for quite some time as likely to transpire at some indeterminate point in the future, the opportunity has come at a much earlier moment than many had thought there was reason to expect. For energy independence advocates, including U.S. Democratic Party policy opinion shapers and so-called thought leaders, these trends and indications would seem to be fortuitous.

That is, in the event that these two phenomena remain linked, and when and if they were to become operational, it should be possible, or so many increasingly believe, for the United States to no longer feel the same urgency to assign as much importance to Arabia and the Gulf as before.[19] To the many in both American political parties that seek to curry favor with Israel and its U.S. support base, and vice versa, such a development would be a dream come true.

Strategic Signaling

The Asia-centric visits and declarations of American leaders have been exercises in strategic messaging. The Obama administration has sought not only to dispel any notion that America may have lessened the overall level of its appreciation for its Asian partners. It has also sought to leave no doubt about its intentions. The administration has aimed, first, to strengthen and expand its presence in the region. Second, it has aimed to reconfirm that America has important interests in Asia that it is determined to protect and, if necessary, defend.[20]

China, however, views such matters differently. Indeed, it is doing so without regard to whether the West is or is not as committed to its interests and involvement in Arabia and the Gulf. China’s leadership clearly is in a revisionist mode. The impact of America’s cautious and measured approach to international conflict resolution during the two-term record of President Barack Obama to date, combined with the Department of Defense’s budgetary cutbacks, has left China with little doubt that the United States nowadays not only has less of an appetite for intervention in foreign affairs than in a very long time but its diminished economic resources would prevent it from doing so even were it inclined. In this context, China’s leaders would only naturally seek to advance their country’s interests in nearby areas.[21] Certainly there is no reason to wonder why or even whether this is happening. A similar phenomenon occurred after World War Two when British imperial power diminished considerably, rapidly, and, in the end, irreversibly.

In the Steps of Britain’s Imperial Demise

In the wake of Britain’s imperial demise, Americans stepped into the Gulf breach for two overarching reasons. First, it was an extraordinary opportunity for the world’s largest consumer and importer of hydrocarbon fuels. Doing so enabled it to strengthen and expand its political, technological, economic, and financial footholds and influence abroad. What was particularly fortuitous in this regard was obvious. It was that the increase in American international strength would occur in the one region of the world more than any other with the most prodigious sources of the commodity driving America’s unrivaled standard of living. Second, there was a belief that the United States had no choice but to proceed in this direction lest Moscow be tempted in ways that America’s Cold War containment stalwarts were determined never to encourage.[22]

With bountiful historical examples buttressing their analyses and perceptions of potential threat scenarios, U.S. policymakers believed the Soviet Union, like their counterparts in Tsarist Russia in centuries past, would be tempted to try to fill the vacuum that Britain had created not only in Iran in particular and to a lesser extent in Iraq, but possibly along the entire length of the western side of the Gulf.

In taking steps to preclude such an eventuality, Washington’s foreign affairs establishment was hardly asleep at the wheel. Rather, it opted to succeed and continue the essence of what the British had long been doing. This took the form of the United States crafting and emulating a tailored version of Britain’s previous extended, unfettered, and low-key but nonetheless activist and overall effective role in the foreign relations and de facto defense of the countries that, ten years later, would come to comprise the GCC.[23]

Some Common Themes

In Arabia and the Gulf, the recent narrative of an America suspected of intending to pivot from the world’s most vital region to one that is arguably of considerably less strategic importance is not a matter of idle chatter. Despite Obama administration officials’ repeated denials that this is occurring or will eventually transpire, the pan-GCC suspicion is and remains that this is indeed Washington’s intention and hence a valid GCC country concern. Hence, too, the incredulity of those within the GCC region who reckon that, if indeed this is or will soon be among the cards Washington will want to play, the United States would have to be a buffoon were it willingly to substantially diminish its overwhelmingly dominant footprint in this hydrocarbons-rich corner of the planet — that any that could would gladly pay to purchase were it to be truly up for grabs.

[pullquote]In Arabia and the Gulf, the recent narrative of an America suspected of intending to pivot from the world’s most vital region to one that is arguably of considerably less strategic importance is not a matter of idle chatter.[/pullquote]Indeed, the incredulous within the GCC region ask, “And for this the United States in the past three decades has thrice sent hundreds of thousands of its armed forces to Arabia and the Gulf, and placed them in harm’s way? Was the blood of the U.S., the GCC and other Gulf peoples, and America’s other allies spilled for naught? Leaving aside the third time — the debacle of the 2003 U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq — wasn’t it the case on the first two occasions when American blood was comingled with Arab and other allied lives lost that it benefited the United States, the GCC countries, and world economic health in general? And did not the United States do so to establish or restore a degree of external defense, security, and stability that had been shattered, threatened, or looked as though its certainty or the prospects for its prolongation might be open to question?”

None doubt that America’s armed forces led the internationally concerted action that ended the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War. Indeed, the United States was the foremost in-region Great Power working in concert with its mainly Western European allies and key GCC country government leaders to achieve that objective. In so doing, it helped accomplish another goal: namely preventing the Iranian Revolution from expanding to the GCC countries.[24] What is more, in tandem with the assistance of several GCC countries’ governments, America’s armed forces during this period helped achieve a third objective. They did more than any other country’s military to help drive the final nail into the casket of the Red Army and the so-called Soviet Bloc, if not international communism itself. And, of course, the United States defense establishment was without a peer in leading the internationally choreographed actions in 1990-1991 that restored sovereignty, safety, and freedom to Kuwait.[25]

Iraq and Palestine: America’s Wrongdoing, Undoing, and Waning

In the eyes of many in the GCC region, the United States has fallen far from its earlier pinnacle of possessing a seeming ability and willingness to do the right thing at the right time for the right reasons with the right people for the right results. What vitiated all the earlier pan-GCC goodwill toward the United States was not only that in 2003 it attacked Iraq, despite the fact that Iraq had not attacked the United States. Neither was it limited to the revulsion at the totally unnecessary and morally repugnant slaughter and maiming of hundreds of thousands of Iraqi, American, and other lives. Nor was it merely the external and domestic displacement of fully a quarter of Iraq’s 24 million people. Nor was it the devastation of vast swaths of the country’s infrastructure as reflected even now, approaching a decade and a half later, in the quality of Iraqi cities’ electricity, water, sewage, educational, and health services being but a fraction of what they were before the invasion. It was also not attributable – at least not solely — to the resulting onset of a humanitarian crisis of epic proportions the likes of which, in the contemporary era, the region has never seen and that remains unabated. Nor was it simply part of the region-wide awareness that the United States is without a peer in having caused the deaths of two million Muslims in the past few decades, with the resultant increase in the spread of anti-Americanism on a scale without precedent in the history of the relationships between Americans and Arabs and Americans and Muslims.[26]

It was the individual and combined impact of all these horrors – inflicted not only upon the country but its people and their resources, not to mention the citizenry’s physical security and the government’s political stability – that shocked and disturbed so many in the GCC and elsewhere. Piled upon decades of despair and disillusionment with America’s policies and actions regarding Palestine, it was not lost on those in the GCC countries that all of these tragic developments ensued as a direct consequence of what the United States did to Iraq.[27]

Killing a Country

The angst in Arab hearts and minds against U.S. policies as a result of what the United States has done to Iraq and has not done with regard to Palestine and Syria was perhaps best capsulized by two quite different, but coupled, analyses and assessments. In the case of Palestine, America more than any other country has, in collusion with Israel, continually prevented the establishment of a sovereign, independent, and territorially inviolable Palestinian state.

In the case of Iraq, as a former GCC Secretary General remarked to me, “Whatever else America did in and to Iraq, it killed a country. It practically devastated an extraordinary array of people.” He added, “And not just any country or people. Rather, the country was Iraq. And the people were the Iraqis – who, in the hearts of the more than 330 million Arabs and the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims, are the heirs of what was long the center of Arab and Islamic civilization at its zenith.”[28]

America Invades Iraq and Iran Wins

Participants at the annual GCC ministerial and heads of state summits that this author attended after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq[29] tried hard but found it difficult to make light of an observation agreed to by practically everyone. Paraphrased, the gist of the observation was the following: “The United States invaded Iraq and Iran won. And it did so without firing a shot or shedding a single drop of blood.” Along those lines, some asked: “Given the longstanding animosity between Tehran and Washington, when before has a power massively more dominant than an adversary presented the adversary a strategic gift of even remotely comparable magnitude as the United States presented Iran in this case?”

Perhaps against this additional background and perspective as context it becomes easier to comprehend much of what otherwise might seem inexplicable.

Bewilderment’s Grounds

What this account has endeavored to do is indicate the grounds for the sustained pan-GCC bewilderment toward Washington officialdom’s alleged intention to rebalance its strategic priorities in Asia while maintaining its interests in the Middle East. More specifically, this analysis has tried to underscore the roots of GCC country disenchantment regarding American foreign policies, actions, and attitudes of late. The reference is to issues that, in the eyes of GCC analysts, are of overriding importance to their legitimate needs, concerns, interests, and major objectives vis-à-vis Iran, Iraq, and the United States.

What has been the impact of the 2003 U.S.-led invasion and occupation of Iraq? One answer is that Washington’s national security elites rode roughshod over most of the GCC country leaders’ strong advice for the United States not to invade Iraq.[30] The consequences have hardly been marginal. Indeed, a maelstrom of disastrous effects followed in the wake of America overriding its GCC allies’ and friends’ counsel. In so doing, by its attitudes, actions, and policies, the United States effectively pulled the rug out from beneath what had for some time been the extraordinarily positive pan-GCC impact of some of its earlier achievements.

Blowback’s Consequences

The blowback to failed U.S. policies unleashed previously contained forces. The ensuing chaos, destruction, violence, looting, and corruption — much of it ongoing — has resulted in the killing and disabling for life of hundreds of thousands of Iraqis over and beyond the untold numbers affected by the U.S.-led sanctions against Iraq throughout the 1990s and continuing to the 2003 invasion.

[pullquote]An American foreign policy establishment seen as partly credible and partly incredible simultaneously in an area such as the GCC region would be humorous were the matters at issue not so serious.[/pullquote]Regarding its reported decision to pivot to Asia to “rebalance America’s strategic footprint in the world,” an American foreign policy establishment seen as partly credible and partly incredible simultaneously in an area such as the GCC region would be humorous were the matters at issue not so serious.

For starters, one need only ponder the potential implications that an actual American pivot could have on Iran-GCC, U.S.-GCC, and U.S.-Iranian relations. The fallout would likely have a worldwide negative impact on stock markets. It would deal a blow to financial investment institutions. It would threaten global security and stability. And it would encourage Iranian assertiveness and possibly aggression, among other things.[31]

“Free Riders?” No

Viewed in this light, many not only in the GCC region but elsewhere wonder whether Washington is certain of the efficacy of the direction in which its foreign policies are headed. This much is clear: the United States is indeed doing two seemingly contradictory things at once. Already, in this regard, reaction to a wide-ranging article about President Obama’s foreign policy views written by Jeffrey Goldberg and published in The Atlantic has been indicative of the angst felt by many within the GCC. In the article, the President allegedly made disparaging remarks about unnamed countries that seemed unmistakably to include one or more among the GCC’s member-states. Embedded in his remarks was the phrase “free riders.” In the minds of many readers, the implication was that the GCC member-states, among others, often bore less than their share of responsibility for the region’s defense and security, owing possibly to the reason that they expected that the United States would carry most of the burden.[32]

The consequences of these perceived trends and indications in America’s overall approach towards the region, embodied in The Atlantic article and beyond, have hardly been trivial. They have been partly disheartening, partly frustrating, and partly a growing source of greater anger, disbelief, and disappointment with regard to U.S. foreign policies than already existed. Such feelings were aptly expressed by former longtime Director General of Saudi Arabia’s General Intelligence Directorate Prince Turki Al-Faisal in Arab News. “No, Mr. Obama. We are not ‘free riders.’” he said.[33]

The Provenance of Strategic Ideas and Concepts

Making sense of the confusion to which this essay alludes requires focusing not so much on Asia but on the GCC region, which is where the uncertainty lies. Doing so begs several questions. Does America have a strategy toward this region? If so, for how long has it had such a strategy? What is the strategy’s nature and extent? And what are its conceptual origins and parameters?

Large numbers in the GCC region believe what the United States is doing in Arabia and the Gulf lacks a strategy. Others conclude that instead of a strategy, Washington, for the most part, has been inclined to offer ad hoc reactions and improvised responses to a disparate array of regional challenges.[34]

There are some who claim that the focus and behavior of the Obama administration are, at best, tactically rather than strategically driven. Within this view, the consensus is that the most important issues, which are arguably at once strategic and tactical, include: (1) maintaining an adequately produced, manageably priced, and effectively administered flow of oil from the region to international markets; (2) keeping the Hormuz Strait open to unfettered maritime commerce; and (3) stemming the influence and spread of Al-Qaeda, ISIS, and other militant extremist and violent ideologies.

Added to these matters are myriad other issues that have to do with Afghanistan, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Palestine-Israel, Syria, Tunisia, and Yemen.

What is one to make of all this?

The Asymmetry of Empathy and Understanding

In regard to the numerous and widespread allegations that America’s approaches to Arabia, the Gulf, and much of the region beyond have been tactical only, this writer strongly disagrees. Indeed, Washington’s policies, positions, actions, and attitudes toward Arabia and the Gulf have all along been and to this day remain grounded, in general, in strategic concepts. These concepts relate to, and emanate from, numerous key turning points and developments in regional and world affairs.

[pullquote]Washington’s policies, positions, actions, and attitudes toward Arabia and the Gulf have all along been and to this day remain grounded, in general, in strategic concepts.[/pullquote]Among the most important are the following: the immediate post-WWII era, Great Britain’s final abrogation of treaty responsibilities for administering the defense and international relations of its nine remaining protected-states lining the shores of eastern Arabia in 1971, the “Twin Pillars” strategy of the 1970s, the 1973-74 oil embargo and ensuing price rises, the 1975 reopening of the Suez Canal shut during the June 1967 Arab-Israel War, the 1979 Carter Doctrine, the 1979 Camp David Accords, the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the 1979-1981 American hostage crisis in Iran, the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War, the 1989 collapse of the Soviet Union, the 1991 Kuwait liberation, the so-called “Arab Spring” uprisings in several countries that commenced in late-2010-early 2011, the dramatic rise in United States energy production since 2010, and others.

The challenge of comprehending the roots of these considerations is admittedly not easy. But neither is it overly difficult. What is required is empathy, the ability and willingness to view the matter through the eyes of the strategy formulation’s participants. Also necessary is to ask difficult and, certainly for some, controversial questions. Some examples follow.

Has the United States sought to advance American interests and policy objectives in Arabia within the context of a strategic perspective?

Has Washington’s approach to the GCC countries been anchored in a strategic appreciation and net assessment of the GCC region?

Costing Minuscule Cultural and Empirical Experience

Unfortunately, any attempt to answer such questions from the U.S. side can be trying. The effort is hampered by the greater inability to understand the Arab side than an ability of the Arab side to comprehend the American side. A core reason is that the number of GCC graduates of American universities exceeds 400,000, whereas the number of U.S. graduates from GCC universities is tinier than minuscule in comparison.

What is sure is that the framework for America’s overall strategic analysis of Arabia and the Gulf was not established in the context of a vacuum. Rather, it was hammered out on the anvil of analytical prisms at given points in time. Importantly, three strategic developments set the American agenda: (1) the 1989-1990 implosion of the Soviet Union; (2) the fall of the so-called Eastern Bloc; and (3) the accompanying end of the decades-old international communist threat.[35]

In retrospect, it is easy to forget what, for the Washington political establishment, were the heady days of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Yet the strategic implications of the communist coffin being slammed shut spread quickly and reverberated far and wide. No less significant, the vertical consequences of interring the unrelenting effort led by Moscow to “bury” capitalism tunneled deeply into the dynamics of the surviving international systems of governments and politics. To Washington policy analysts in search of a more congenial strategic environment within which to pursue American national interests from then onward, the result could hardly have been more favorable: the United States, for the first time in its history, had indisputably become the world’s preeminent power.[36] The implications of the new reality were not lost on American officials tasked with charting the way forward.

Anchored Phenomena

America’s policy planners and decision makers were aware that such a moment could not endure indefinitely. They recognized that the ensuing geopolitical advantages and economic benefits, together with the privileges and rewards associated with what had been termed “the American Century,” unprecedented as they were, could not be sustained without effective leaders of conviction and commitment. Such leaders would have a chance to prolong the unipolar moment only through the formulation and implementation of a sound, long-term, strategic vision.

The strategic analysts of the day concluded that this auspicious juncture in America’s history could best be extended if it were anchored in four phenomena. One was the availability of and access to adequately produced amounts of manageably priced hydrocarbon fuels. A second was the assurance of sound planning and preparation. A third was the availability of the requisite and ongoing human, economic, financial, and technological resources. And, above all, a fourth was the steady presence of a visionary, decisive, and strategically focused leadership.[37]

Just as vital would be the effective aid of working partners. Ideally such partners (think GCC countries) would have economic clout, financial wealth, geological might, and/or geopolitical weight – and preferably all three. More important would be for such actors to attempt to translate whatever influence they might have and be willing to exert into appropriate actions. Again, ideally, for the focus of their influence to be the most effective, it should be on issues and interests of importance to key foreign policy objectives within regional circles and major international organizations.

“Yankee, Don’t Go Home!”

Whatever new or elevated priority America may have assigned to its strategic relations with Asia at the time that the so-called coming pivot was proclaimed, the following was and remains of overarching importance. One should not expect to see any significant diminution in the overall strategic importance America has assigned to the GCC countries and the Gulf as a whole in comparison to the Asia-Pacific region.

[pullquote]One should not expect to see any significant diminution in the overall strategic importance America has assigned to the GCC countries and the Gulf as a whole in comparison to the Asia-Pacific region.[/pullquote]Dispelling any doubt about America’s resilience and resolve to take seriously its Gulf defense responsibilities was the extraordinary effectiveness, as previously indicated, of the U.S.-led internationally-concerted action in 1990-1991 that reversed Iraq’s aggression against Kuwait. No other country could have led such a global assemblage of effective power to help restore and render safe and secure to Kuwait and all the GCC countries what was vitally important to each, namely their national sovereignty, political independence, and territorial integrity.[38]

To American planners in search of a recalibrated vision and mission, the plaintive pleas scrawled on the walls of the U.S. Embassy in Kuwait after the country’s liberation, when this author was aboard the first civilian aircraft to land in the territory from which Iraq’s aggression had been reversed, said everything: “Yankee, don’t go home.” This was the context during the final months of the Bush 41 administration when the then-U.S. Secretary of Defense tasked the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy with drafting a long-term strategic plan that would ensure that the United States in 2020 would retain its position as the world’s only super power.[39]

Five Contextual Criteria

Not long after the plan’s drafting was underway,[40] a Department of Defense representative invited me to brief his foreign policy colleagues. He wanted to ascertain my views on what were then the most pressing challenges to America’s interests and policies in the GCC region. An additional goal was to critique the “20-20” strategic plan – subsequently referred to as the Defense Policy Guidance – that he and his colleagues were then involved in conceptualizing and writing.

My host informed me that the analysts and writers of the Guidance had reached a preliminary consensus as to how the United States could meet its strategic objectives. He said that they had concluded that, for the United States to remain the uncontested globally preeminent power, it would have to adopt the following long-term policies. America, they contended, would have no choice but to remain preeminent in five separate but interrelated fields of power: economy, finance, technology, military, and industry. It was understood that regardless of the toll the pursuit of these objectives might have on the American economy, the United States must maintain superiority in each area. Otherwise, they agreed, America would not be able to retain its paramount international position, power, influence, and role.

Energy the Key

Asked whether any one single factor might be essential to all five categories, my response was that energy was such a factor. Energy, everyone agreed, was and is the one commodity, more than any other, which drives the engines of the world’s economies and, thus, humanity’s health, defense, security, and material well-being. More than that, energy directly affects the three commodities upon which all are dependent: air, water, and food.

The question of whether “Our energy or someone else’s” seemed trickier. My response was “Someone else’s” with a caveat: “ but only if, at all, possible and feasible – meaning not immorally, manipulatively, exploitatively, and/or at the expense of others’ legitimate needs and rights.”

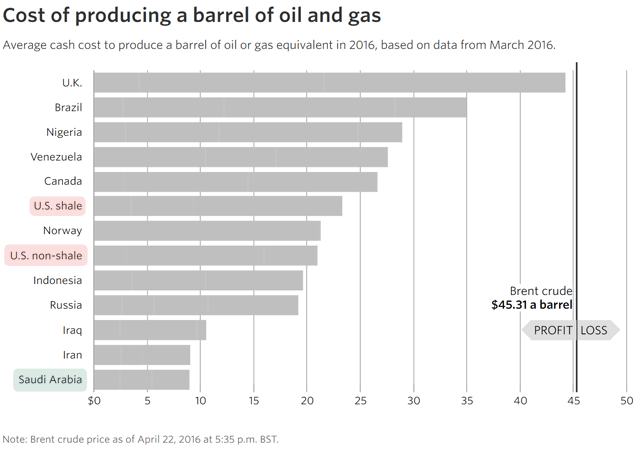

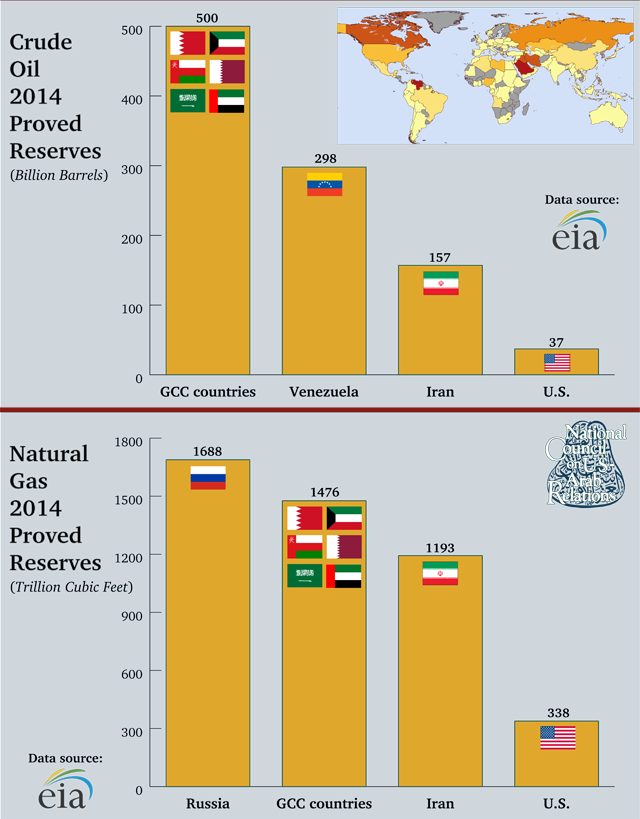

The question was then, “Where does the GCC region fit into this strategy?” The reply was that, regarding supplies, the GCC countries are the engines of the world’s economies. Figures produced by the U.S. Department of Energy, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, and BP reveal the reality. The GCC member-states account for around thirty percent of the world’s proved crude oil reserves and around twenty percent of the world’s proved natural gas reserves. Saudi Arabia alone has sixteen percent of the world’s proved crude oil reserves –with many oil fields that as yet have never been tapped — and its largest oil field (Ghawar) has more proved reserves than all but seven other countries. Iran and Iraq combined account for an additional eighteen percent of proved oil reserves and nineteen percent of proved gas reserves.[41]

The cost of oil production in the GCC region is also significantly less than production from both shale and non-shale reserves in the United States due to the oil fields being larger and closer to the surface. Additionally, the long-term per unit production level of GCC member-states’ oil wells is vastly higher than the production level of American wells.[42]

Facts are Stubborn Things

Facts and geopolitical realities are stubborn things – they have implications for policies. As is the case with other realities, the implications for policymakers worldwide in this instance – and in conjunction with any serious American intent to rebalance its priorities away from Arabia and toward Asia – are, or ought to be, obvious This should be the more so given that the world’s most adequately produced, manageably priced, and prodigious energy exports are located primarily not in Asia but in Arabia and the Gulf.

[pullquote]The world’s most adequately produced, manageably priced, and prodigious energy exports are located primarily not in Asia but in Arabia and the Gulf.[/pullquote]Also clear, and hardly the least important among considerations for American strategic analysts, is what could prevent the United States from reaching 2020 with its preeminent 1992 status intact: America’s competitors. There is every reason to believe that Washington’s rivals in 1992 for global prominence were in agreement then and now regarding the importance of the same five fields of activity as the ones identified here.

Such fields are those in which other countries, too, would have little choice but to perform well. Arguably in no other way would they have any chance of effectively challenging America’s global position in terms of overall power and influence. The foremost competitors then as now have been China and Russia. Others possibly able to mount a credible challenge over time include the heavily populated developing countries, such as Brazil, India, and South Africa, which have their own rapidly growing and increasingly energy-hungry economies.

A Look at the Scorecard

Where is the United States in terms of the strategic objectives it set out to achieve in 1992? Without a doubt, it has remained the world’s most militarily powerful country. In addition, with an annual GDP of close to $18 trillion in 2015, America’s economy remains the world’s largest, over 60% greater than the production of China, its foremost economic rival.[43] In addition, the global financial system, with the preeminence of the U.S. banking system, is still intact.[44] Moreover, as Americans continue to recover from the U.S.-induced 2008 global financial crisis, despite a rising challenge from the so-called Shanghai-based group of countries opting to switch to a different currency reserve, the American dollar seems likely to remain safe for the foreseeable future. As such, it should be able for the time being to continue to reign dominant as the principal monetary instrument of exchange for most international business transactions.

Further, the U.S. strategic telecommunications, information, cyber, and transportation infrastructure within America’s industrial base has remained in place. What is more, the ongoing prowess of American technology – and the extent to which the United States continues to invest in technological research and development and in efforts to prevent or counter infringements upon intellectual property rights and patented inventions – is still supreme worldwide.

Thus, the strategic planners of 1992 have helped to ensure that the United States is well on its way to meeting the goals that were set for 2020. More particularly, they have met their objectives. For the purpose of this essay, the most important ones are those that they set with regard to the specific roles they expected Arabia and the Gulf – in other words, the GCC countries – to play in helping to prolong the array of benefits associated with “the American Century.”

No Easy or Inexpensive Riding

As positive as this may sound, America’s achievements in the five categories of measurable might and associated influence have not been free of cost. The road along the way has been bumpy. Here and there, it has also been disastrous.

With regard to the latter, some crises were unforeseen. Other disasters were anticipated but with a degree of seeming American inaction and indifference in the face of the tragically unjust results that ensued. By any standard, the consequences – read Iraq; read Palestine; read Libya; read Syria; read Yemen – have been and continue to be unconscionable.

The positive accomplishments, moreover, did not occur in a vacuum. Rather, they happened often in association with contentious, heavy-handed, at times brutal, often unaccountable, and internationally illegal means. If – and this is admittedly a very large “if” – one can put to the side what many consider to be these morally audacious U.S. actions, together with America’s violations of international law and the norms of international legitimacy, it is difficult not to conclude that Washington has thus far succeeded in meeting the overall goals of the 1992 strategic plan.

The View Less Seen

There may be widespread disagreement among a variety of observers who have bought into the idea that America is “pivoting” to Asia. But observers in the GCC region offer a different perspective.

GCC analysts have argued that not only do America’s strategic goals pertaining to their region remain largely intact. They are also quick to note that the United States’ strategic investment in the region has not been cheap. It has been accompanied by the expenditure of trillions of dollars and a horrific scale of sheer destruction in human lives, limbs, and minds. This has been largely occasioned by the American-led invasion and occupation of Iraq combined with the earlier ruinous regime of international sanctions imposed by the United States and the entire United Nations membership upon that country and its people.

[pullquote]GCC analysts have argued that not only do America’s strategic goals pertaining to their region remain largely intact but also that the United States’ strategic investment in the region has not been cheap.[/pullquote]An additional self-inflicted wound has been the United States’ tacit and overwhelming domestic support for Israel’s ongoing fulfillment of its quests for territorial and resource acquisition at the expense of the Palestinians and Syrians. That much of this American favoritism and seemingly unlimited backing of Israel has been and continues to be rooted domestically within the American body politic is a reality that only the most hardened GCC political realist and strategic analyst can find the means to accommodate.

Why Pivot from “Success?”

That such an accommodation has nonetheless proceeded to be manifested by this, that, and the other GCC country foreign policy practitioner is not by accident. It is due as much as anything else to the pan-GCC view that thus far there is no viable alternative to the United States as the region’s ultimate protector. Nor do most GCC policymakers envision an effective replacement in the foreseeable future for the myriad other things that they and their constituents seek to obtain from the United States – if not for themselves, then for their progeny and succeeding generations.

Leaving aside the negative aspects associated with America achieving thus far what it set out to accomplish in 1992, and with four years remaining to reach the end game envisioned for 2020, there is a nagging question. Why switch the focus to Asia, where international forces and variables are as yet unclear? Why do so when the prospects for a level of success comparable to that achieved in Arabia and the Gulf would seem uncertain?

Why, when the dynamics of this region in terms of America’s necessities, apprehensions, and interests are nowhere nearly as in alignment as they have long been between the United States and the GCC countries? And why do so, given that Asia, at least thus far and arguably for the foreseeable future, arguably can hardly compare to the GCC region in terms of globally strategic energy and economic relevance and benefit?

None of this is meant to imply that the forces and factors propelling the reported shift in American strategic priorities are not understandable. They are. What is at issue, however, is something else. It is what is not being said and not being written about – it is the masked and questionable motives and the intended end games of those promoting the “pivot policy.”

So Many Questions

So then, what might be driving the narrative surrounding this supposed policy shift?

Within the American military establishment, is there in play even a hint of inter-service rivalry among America’s uniformed armed forces?

Does the purported rationale for turning from Arabia to Asia have anything to do with the corporate bottom lines of the defense and aerospace sectors, on one hand, and future Congressional budgetary outlays, on the other, for the country’s costly high-ticket navy and air force?

Is it the case that competition for the shrunken defense budgets affecting the various military branches is at the root of what is prompting the shift in strategic focus from the GCC region to Asia?

Hyping an Existent or Non-Existent Challenge?

Is the arms manufacturing sector of the U.S industrial base and its important role in the American economy not a major albeit largely unspoken factor fueling at least a portion of this debate?

Might the road to maintaining infusions of American taxpayer dollars into this sector of the economy be underpinned by routes to, through, and in and around Asia?

Could it be that some see the paving of such routes potentially enhanced by hyping a largely non-existent challenge in a part of the planet that many at present do not view as threatening?

If the market for exporting arms to the GCC countries’ defense sectors might be satiated for the foreseeable future, can anyone not understand the logic of those whose livelihoods are dependent upon this sector doing whatever is necessary to devise seemingly plausible reasons for generating sales elsewhere?

Anyone for Conspiracies?

Shifting the focus and search for causal factors in a different direction produces additionally possible insights.

To what extent, if any, are Israel and its American supporters’ strategy of deflecting negative international focus from the Jewish state eastward – a crisis in New Zealand would be ideal, although short of that, the GCC region would suffice – in play here?

Can one dismiss the logic of such a strategy? Does one need to be a conspiracy theorist to give any credence to Israel’s understandable support for a pivot? Namely, a pivot away from the Eastern Mediterranean, Israel’s ongoing theft of land and water in the Occupied Palestinian and Syrian territories, and Israel’s innumerable violations of international law and of United Nations Security Council resolutions?

Does it not follow that an American pivot from Arabia to Asia has relevance for Israeli strategists and leaders?

Deception and/or Distraction and/or Substitution?

Is the Obama administration’s failed effort to conclude an Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement, with the implication that Israel would have been required to grant concessions it wishes to avoid, lacking in applicability in this regard?

Is it not in Israel’s strategic interests to hype the global strategic importance of the Indian Ocean – one of the world’s main maritime routes – to and from the Asia-Pacific region, and in doing so downplay the importance of Arabia, the Gulf, and the GCC region?

Is there a replay of previous Israeli strategies afoot? Does this resemble previous Israeli governments’ efforts to periodically single out Lebanon, Syria, Iran, and/or Iraq, and, from time to time, even Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Sudan, or Yemen for international attention – but not itself?

Is this a re-run of Israel’s attempts to divert attention away from concluding a peaceful, negotiated, enduring, and comprehensive political settlement over Occupied East Jerusalem, the West Bank, the colonies/settlements, water, and Palestinian refugees?

Suspicion Mongering?

Further, why would America seem to be determined to embark upon a different strategic regional emphasis when doing so would appear to risk arousing deep and widespread suspicions of its true intentions in Asia, with China’s strategic analysts as a result having reason to believe that they are being encircled by an American-centric alliance?

And why do so where, among friends at least if not also adversaries, the grounds for such suspicions were not present before?

Would the reason solely be to strengthen U.S. capabilities to observe and, if need be, respond to future developments in the region, inclusive of a potentially expansionistic China at some point, as noted earlier?

If so, would the United States be willing to reciprocate were China to seek to encircle America?

Is it in U.S. interests to awaken in America’s leaders and elites, let alone the broader American public, an unwarranted impending fear of Asia?

Asia’s Perceptions?

Alternately, does the United States want to implant in Asia the perception of an American threat?

Does the U.S. government want to provoke the Chinese government, which would understandably not look kindly upon a country or people that needlessly antagonizes and provokes them?

Are America’s Asian allies really in dire straits either now or in the foreseeable future, of an external threat from any regional or global challenge or challenger?

Or, if not, might an America seen as facilitating, strengthening, and expanding its assets in Asia be unnecessarily providing grounds for such challenges, would-be challengers, or even mere competitors to be perceived as threats?

Are the possibly coming trends in the Asia-Pacific region likely to be of such an ominous nature as various American fear-mongers and powerful interest groups would have the U.S. government, media, and general public believe?

A Necessary Intrusion?

And with Okinawa and South Korea as points of reference, together with China’s occupation of disputed Asian islands, are the alleged threats likely to be used in support of a greater intrusion of America’s armed forces into a region where, in the eyes of its inhabitants, larger numbers of U.S. troops than already exist may neither be wanted or perceived as necessary?

Most importantly, would it not be the height of strategic folly for the United States to even pretend to look at imaginary greener pastures when to do so and to begin to activate military measures in support of such a view risks a future more uncertain than the one that exists?

Why do so in light of the additional taxpayers’ expenditure in troops and treasure that would likely be required to make the envisioned pivot?

Even if one’s analyses and assessments are confined to the realm of strategic thinking as opposed to acting, why would one contemplate acting thusly so openly at the expense of frustrating one’s longstanding partners and allies and potentially antagonizing and provoking others?

Why do so, given the tens of thousands of Iraqis, Americans, and others killed, wounded, and maimed for life in the wake of the lingering effects of the U.S.-led invasion, occupation, and subsequent war in Iraq?

And why do so amid the clouds of uncertainty in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and attendant anxieties associated with the rising fortunes of anti-American and anti-American allies’ insurgents from Iraq to the Mediterranean? In all of this, where is the strategic merit?

Conclusion

A final question concerns the media’s heavy dependence upon private sector advertisers, which are known to have strong ideological and political views and may stand to gain economically from a shift toward Asia. If such pressures prevail, might this create a source of otherwise inexplicable media influence and pressure in the pivot-to-Asia narrative that is being fed to the American public? The fact that American mainstream journalism has largely failed to examine and explain the questions, concerns, and issues raised and addressed herein should be a matter worthy of investigation.

In the final analysis, the transition of a country’s strategic and foreign policy approach from one region to another is neither easy nor cost-free. This is especially so when considering a pivot from an existing overall successful approach to one region toward another region where the alleged merits are questionable and debatable, the prospects dubious, and the potential repercussions with regard to costs, rationale, efficiency, and necessity are serious and far-reaching.

In this instance, it is difficult to make sense of the “Pivot to Asia School” compared to the merits of the “Stand by One’s Friends School.” It is also difficult to imagine how it would be necessary or wise for the United States to imply it is pivoting from an area that is far more strategically vital globally than the Asian countries are or could realistically become in the immediately foreseeable future.

Why contemplate doing what appears to be neither necessary nor desirable at the expense of stirring up anxieties and in some cases despair among one’s strategic partners and in-region allies? And why do so when the act itself would make no sense to America’s strategic friends? Indeed, why do so knowing that the leaders of America’s foes would trade places with the United States in a second were it seriously to contemplate pivoting from the GCC region to Asia, let alone actually do so?

[1] The Fifth Ministerial Meeting of the GCC-U.S. Strategic Dialogue was held on September 30, 2015, in New York. See Office of the Spokesperson, Media Note, U.S. Department of State, Washington, DC, September 30, 2015, http://1.usa.gov/1r5Cjby.

[2] Former Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel stated at the U.S.-GCC Defense Dialogue, May 14, 2014: “In recent years, the United States’ defense cooperation with the nations of the GCC region has dramatically expanded…This has been demonstrated by the United States Central Command’s continued, forward military presence, which includes 35,000 personnel; our Navy’s Fifth Fleet; our most advanced fighter aircraft; our most sophisticated intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance assets; and a wide array of missile defense capabilities. It has also been demonstrated by recent defense sales agreements, including some of the largest in American history.” See Secretary of Defense Speech, U.S. Department of Defense, Washington, DC, May 14, 2014, http://1.usa.gov/1r5Cp2Q.

[3] Frank A. Rose, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Bureau of Arms Control, Verification and Compliance, discussed the importance of U.S.-GCC cooperation for political and economic security. See Gulf Cooperation Council and Ballistic Missile Defense, U.S. Department of State, Washington, DC, May 14, 2014, http://1.usa.gov/1SA2K24.

[4] George Perkovich, Brian Radzinsky, and Jaclyn Tandler contend that GCC countries have worked with the United States in power balancing in the region to prevent potential nuclear escalation with Iran. See “The Iranian Nuclear Challenge and the GCC,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, May 31, 2012, http://ceip.org/1VIgvQa.

[5] Philip Seib of the University of Southern California, for example, suggested that “in the United States and elsewhere in the West there is a decided ‘Arab fatigue.’” See Seib,“Arab Fatigue and Today’s Middle East,” Huffington Post, June 30, 2014, http://huff.to/1U9gmnd.

[6] Nabeel Khoury, “GCC Wrath, Talk of Unity, and Beyond,” The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, December 12, 2013, http://bit.ly/249mEGj.

[7] On U.S. and GCC views regarding U.S. policy in Syria and Egypt, see “Despite Tensions, U.S.-GCC Relations Strong,” Defense News, November 10, 2013, http://bit.ly/1VrsaCG.

[8] Brandon Friedman, “Battle for Bahrain: What One Uprising Meant for the Gulf States and Iran,” The World Affairs Journal, April 2012, http://bit.ly/22UTkRf.

[9] For the regional and global threat Hizbollah poses, see Thomas Donilon, “Hezbollah Unmasked,” The New York Times, February 17, 2013, http://nyti.ms/1SA368L.

[10] Prince Turki Al Faisal discusses the importance of the GCC joining talks with Iran in “GCC ‘Must Join P5+1 Iran Talks,’” Gulf News, December 8, 2013, http://bit.ly/1T4qbxV.

[11] “POMED Notes Changing Dynamics in the Gulf, GCC, Iran, and the U.S.,” Project on Middle East Democracy review of the Stimson Center event, “Changing Dynamics,” Washington, DC, July 2, 2014, http://bit.ly/1VNI4XL.

[12] Kelly McEvers, “Support for Iraq’s Maliki Puts U.S., Iran in the Same Camp,” NPR, September 20, 2010, http://n.pr/1VNI8qv.

[13] President Barack Obama announced at the beginning of January 2012 a new Defense Strategic Guidance (DSG) that, among other things, emphasized a strategic geographical shift of priorities to East Asia and the Pacific, while maintaining current interest in the Middle East. On the DSG, see Catherine Dale and Pat Towell, “In Brief: Assessing the January 2012 Defense Strategic Guidance (DSG),” Congressional Research Service, R42146, Washington, DC, August 13, 2013, http://bit.ly/1SC4wCS. Obama then announced at the beginning of February 2015 a new National Security Strategy (NSS) that for the first time classified its objectives by geographic region, and explicitly reemphasized its strategic shift to rebalance Asia and the Pacific while continuing to further stability in the Middle East and North Africa. On the NSS, see Nathan J. Lucas and Kathleen J. McInnis, “The 2015 National Security Strategy: Authorities, Changes, Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, R44023, Washington, DC, February 26, 2015, http://bit.ly/249mXkl.

[14] Abdullah Al-Shayji, “Overhauling the GCC-U.S. Partnership,” Gulf News, May 4, 2014, http://bit.ly/1SpqJ1E.

[15] “Letters from America: Selling U.S. Exports to Asia’s Middle Class Consumers,” China Briefing, October 22, 2012, http://bit.ly/1Wi7JH3.

[16] “Washington’s Nightmare Comes True: The Russian-Chinese Strategic Partnership Goes Global,” Global Research, August 23, 2014, http://bit.ly/1r5Dtnl.

[17] Trevor Moss, “Obama’s Visit Signals Progress for Asia ‘Pivot,’” Wall Street Journal, May 2, 2014, http://on.wsj.com/1U9gP8Z.

[18] H.E. Abdulla Y. Bishara noted a turn in American geostrategic planning toward lessening United States dependence on GCC countries’ oil dating to the mid-1970s oil crisis. See John Duke Anthony, “The Founding of the Gulf Cooperation Council: A Retrospective and Diplomatic Memoir,” December 29, 2015, http://bit.ly/1Sie9o8.

[19] See the discussion by Loren Thompson, “What Happens When America No Longer Needs Middle East Oil?” Forbes, December 3, 2012, http://onforb.es/2161jvx.

[20] The expanding relationship between the United States and Asia is described in “Asia Task Force: U.S.-East Asia Relations: A Strategy for Multi-Lateral Engagement,” Council on Foreign Relations, Washington, DC, November 2011, http://bit.ly/1SA4g4l.

[21] On the other hand, Zack Beauchamp argues that China is in no condition to replace the United States as the world’s leading superpower. See Beauchamp, “China Has Not Replaced America – and it Never Will,” The Week, February 13, 2013, http://bit.ly/1pr2UhK.

[22] See an outline of the motivations and interactions of the United States in the Middle East following World War Two in Mike Shuster, “The Middle East and the West: The U.S. Role Grows,” NPR, August 23, 2004, http://n.pr/1VNJqBS.

[23] Julie Finnin Day outlines the history of American political action in the region in “50 Years of U.S. Policy in the Middle East,” The Christian Science Monitor, September 27, 2001, http://bit.ly/1MOebEd.

[24] James Russell, “Searching for a Post-Saddam Regional Architecture,” in Brian Loveman, ed., Strategy for Empire: U.S. Regional Security Policy in the Post-Cold War Era, Vol. 2 (Lanham, MD: Roman and Littlefield, 2004), 101-121.

[25] See, inter alia, “From the Archive: 28 February, 1991: The Liberation of Kuwait,” The Guardian, http://bit.ly/1YLZjab.

[26] Chas Freeman, “The End of the American Empire,” April 2, 2016, http://bit.ly/1TofF7i.

[27] The Global Policy Forum details the timeline and effects of American and international economic sanctions on Iraq in “Sanctions Against Iraq,” Global Policy Forum, http://bit.ly/1qH9H83.

[28] Author’s interview with a former GCC Secretary General, March 2009.

[29] GCC Heads of State Summits in 2003, 2004, and 2005.

[30] Christian Koch explores the involvement of the United States in Iraq in the 2000s in the context of GCC security and expectations of American support (and subsequent tensions with the United States upon its decision to invade) in “The GCC as a Regional Security Organization,” KAS International Reports, November 2011, http://bit.ly/1SC5MG9.

[31] See, inter alia, Naofumi Hashimoto, “The U.S. ‘Pivot’ to the Asia-Pacific and U.S. Middle East Policy: Towards an Integrated Approach,” Middle East Institute, March 15, 2013, http://bit.ly/1XNFpLH.

[32] Jeffrey Goldberg, “The Obama Doctrine,” The Atlantic, March 10, 2016, http://theatln.tc/1TofKrN.

[33] Prince Turki Al-Faisal, “Mr. Obama, we are not ‘free riders,’” Arab News, March 14, 2016, http://bit.ly/1VIi68C.

[34] Anthony Cordesman, “U.S. Strategy in the Gulf: Shaping and Communicating U.S. Plans for the Future in a Time of Region-Wide Change and Instability,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington, DC, April 14, 2011, http://bit.ly/1qH9MID.

[35] Rashid Khalidi and Lynn Neary, “Tracking the Cold War’s Legacy in the Middle East,” NPR, March 24, 2009, http://n.pr/1T4r8Gs.

[36] Michael Lind, “Beyond American Hegemony,” The New America Foundation, Washington, DC, May/June 2007, http://bit.ly/1qH9Msc.

[37] Kenneth N. Waltz, “Structural Realism after the Cold War,” International Security 25, 1 (Summer 2000), http://bit.ly/1SW5BiS.

[38] Louis Kriesberg,“The Political Psychology of the Gulf War: Leaders, Publics, and the Process of Conflict” (book review), American Political Science Review 88, 3 (September 1994), http://bit.ly/26lb8ti.

[39] Bernard Weiner, “A PNC Primer: How We Got Into this Mess,” CounterPunch, May 27, 2003, http://bit.ly/1VIigwS.

[40] In late spring-early summer 1992.