President Obama’s Coming Visit to Saudi Arabia in Perspective

That the foreign policies of various governments often appear to be contradictory is because they frequently are. Certainly of late, this seems to characterize aspects of the Obama administration’s relations with the six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

This ambiguity and the confusion and uncertainty that accompany it are among the things that President Barack Obama will need to dispel and clarify in the course of his upcoming visit to Saudi Arabia. As this essay seeks to demonstrate, what he will have to contend with in terms of background, context, and perspective will not be easy of resolution, amelioration, or even abatement.

Despite the many largely unreported positives there are numerous negatives that need to be addressed lest a situation that is seen by many within this globally vital region as increasingly tendentious and quarrelsome become the more so, for no good reason.

On one hand, Washington has strengthened and extended its overall position and influence in the GCC region. For example, the multi-year, multifaceted U.S.-Saudi Arabia Strategic Dialogue has been elevated for the past three years to a GCC-U.S. Strategic Dialogue, and there have been strategic, reassurance-themed visits to multiple GCC countries by U.S. Secretaries of Defense and State Chuck Hagel and John Kerry.

Additionally, there have been continuing sales to GCC countries of tens of billions of dollars of U.S.-manufactured defense and security structures, systems, technology, and arms. ((“$10.8B U.S. Arms Sale Reassures Gulf Allies at Touchy Time,” United Press International. October 18, 2013. http://www.upi.com/Business_News/Security-Industry/2013/10/18/108B-US-arms-sale-reassures-gulf-allies-at-touchy-time/UPI-92581382116294/.)) Americans have also signed long-term contracts with these countries for the provision of munitions, maintenance, repairs, spare parts, and equipment sustainability, all of which have translated into the generation and extended life span of millions of American jobs.

Yet, simultaneously, signals from Washington and the mainstream U.S. media indicate that the Obama administration is recalibrating the strategic focus of its international priorities. Great emphasis, for example, is being placed on the Asia-Pacific regions.

Affecting the need to recalibrate are major budget reductions and their impact on strategic concepts, forces, and operational dynamics. At issue and under examination, according to the Secretary of Defense in advance of the Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) are America’s assumptions, ambitions, and abilities. ((Richard L. Kugler and Linton Wells II, Strategic Shift: Appraising Recent Changes in U.S. Defense Plans and Policies. Washington, D.C: Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Institute for National Strategic Studies, National Defense University, 2013. p. vii.)) Understandably, the GCC region’s reaction to these trends and indications has been mixed.

Pluses

On the positive side, many among the region’s strategic analysts and policymakers are pleased with the continuing high-level of military, security, and intelligence cooperation. Others appreciate that America’s forward deployed land, air, and naval forces have ensured the ongoing safety of the region’s oil exports and preserved the member-states’ national sovereignty, political independence, territorial integrity, and security.

And still more have welcomed the Obama administration’s Presidential Directive to allow the United States to sell American-manufactured defense items to all six of the GCC countries. Such sales are expected to be in tandem with the American and GCC joint goal of establishing an effective missile defense system capable of deterring and defending against any and all would-be airborne threats to their self-defense.

All of which has contributed, indeed has been key, to the regionally unrivalled degree of governmental stability from one GCC country to the next. Such stability has been and continues to be the prerequisite not only for maintaining but also for strengthening the sinews of trust and confidence between Americans and Arabs in this particular corner of the Arab world.

The ongoing results, understandably, have been and continue to be the envy of America’s and the GCC’s allies and adversaries across the globe. And institutionally in the case of the GCC, they are viewed by many as exemplars by the GCC’s counterparts among the member-states of practically every other known sub-regional organization.

All agree that, without these characteristics, trends, and indications, there would not be the underpinnings of the region’s unprecedented and extraordinary levels of robust international investment and trade. Nor would there be the steady increase in the number of joint commercial ventures between local companies within the GCC region and the world’s most successful foreign corporations from virtually every quadrant on the planet.

GCC policymakers are also relieved that, so far, effective U.S. diplomacy has averted an American and/or Israeli armed attack against Iran’s nuclear facilities and prevented the near certainty of an international conflict that such an action could provoke. ((Dr. John Duke Anthony, “U.S.-Saudi Arabia Relations Reconsidered,” National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations’ Arabia, the Gulf, and the GCC Blog. October 31, 2013. http://ncusar.org/blog/2013/10/saudi-arabia-us-relations-reconsidered/.))

All the same, America, America’s allies, and, most important, the Gulf countries are weary of wars in this region.

On the negative side, many chafe at the continued unwillingness of the United States, in concert with Saudi Arabia and other GCC countries, to do whatever is necessary to bring down the Syrian regime. Only thus, many contend, could Iran’s ability to foment and sustain the civil strife in Iraq and the domestic dissension in Bahrain, other GCC countries, and beyond be weakened. ((Dr. John Duke Anthony, “Strategic Dynamics of Iran-GCC Relations,” in Jean-Francois Seznec and Mimi Kirk, eds., Industrialization in the Gulf: A Socioeconomic Revolution. London: Routledge, 2010, pp. 78-102. http://ncusar.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/2010-08-04-Strategic-Dynamics-Iran-GCC.pdf.))

Further, some believe it is the only way to constrain Tehran’s relationship with Lebanon-based Hizbollah, which many believe to be an Iranian subsidiary. The concerns of GCC observers are not inaccurately based. Members of Hizbollah’s international networks are organized, trained, disciplined, capable, and ready at a moment’s notice to strike anywhere to create crises and wreak havoc the world can ill afford to suffer.

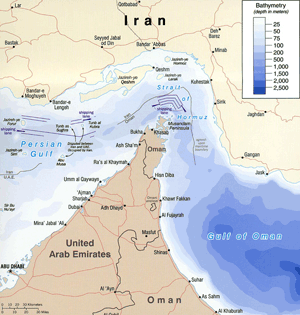

In these regards, no one should doubt the pan-GCC opposition to the Islamic Republic’s longstanding designs on and covert intrusion into the domestic affairs of Bahrain. ((Dr. John Duke Anthony, “The Intervention in Bahrain Through the Lenses of Its Supporters,” Abu Dhabi: Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research. June 30, 2011. http://ncusar.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/2011-06-30-Intervention-in-Bahrain.pdf.)) Though small in size and population, Bahrain plays an outsize role in the safe flow of Gulf energy sources through the Hormuz Strait and all of the regions’ seaborne imports via the same waterway. In addition, its land-based American naval forces are vital to the security and stability of the Gulf as a whole as well as the entire eastern Arabian littoral from Kuwait to Oman.

Additional GCC dismay is rooted in the perceived backtracking and flip-flopping of American actions towards Egypt, given that the Mubarak regime had been a stalwart American ally for thirty years. ((Dr. John Duke Anthony, “Springtime in Washington: Mubarak’s Visit,” Pharaohs Magazine, 2000. http://ncusar.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/2001-04-24-Springtime-In-Washington.pdf. See also, David D. Kirkpatrick and Mayy El Sheikh, “In Egypt, a Chasm Grows Between Young and Old,” The New York Times, February 16, 2014.)) Embedded within such sentiments are echoes of 1979, when – in contrast to Vladimir Putin’s steadfast Russian support for the Assad regime in Syria – America proved unable and unwilling to stand by the Shah of Iran in late 1978 despite having engineered the Shah’s return to power after his fleeing the country in 1953 immediately prior to the U.S.-led overthrow of Mohammad Mossadegh, the country’s first democratically elected prime minister. ((Stephen Kinzer, All the Shah’s Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror. New Jersey: Wiley, 2003.))

GCC member-state representatives resent the P5+1 (the five UN Security Council members – China, France, Great Britain, Russia, and the United States plus Germany) having excluded them from the U.S.-led negotiations with Iran, their largest, far more populous, militarily stronger, and threatening neighbor. Together with regional analysts and private sector communities, they wonder whether their governments might be next on the list of America’s partners whose leaders become disregarded and, ultimately, deemed dispensable. They cannot help but question whether America will stand by its longtime friends and strategic allies.

Added to these negative interpretations and anxieties is the GCC-wide suspicion of an untimely, inordinate, and unwarranted American intention to pivot from the GCC region towards not just Europe and Latin America, but, especially, Asia.

Feeding such apprehensions, in addition to the consequences of the severe U.S. government budget cutbacks, the lure of Asia’s vastly greater consumer markets for American exporters, and the associated prospects for generating jobs, have been high-level Obama administration visits to countries in the Asia-Pacific region accompanied by declarations of ongoing U.S. support for key American and Asian foreign policy objectives.

Such declarations have occurred alongside ruminations that, with America’s domestic oil and gas sectors producing at record-high levels, there is no longer the need or urgency for the United States to assign as much importance to Arabia and the Gulf.

Strategic Signaling

The Asia-centric visits and declarations of American leaders have been exercises in strategic messaging. The Obama administration has sought not only to dispel any notion that America may have lessened its overall level of appreciation for its Asian partners. It has also sought to leave no doubt about its intentions.

The administration seeks, first, to strengthen and expand its presence in the region. Second, it has sought to reconfirm that America has important interests in Asia that it is determined to protect and, if necessary, defend.

There may also be domestic political messaging reasons for the “pivot to Asia” narrative that have come from the Obama administration – that more than undertaking any real-life strategic action the administration has sought to “re-brand” American foreign policy away from the unpopular Middle East-focused disasters of the Bush administration.

Many have commented that the “pivot to Asia” branding is merely putting a label on what has been a growing trend for decades of Asian economic growth and partnership, and is more a linguistic differentiation by the Obama administration than any actual American strategic move.

That this has been in some ways a political marketing maneuver has seemingly been unrealized by many U.S. allies as it appears the Obama administration has been ineffective in communicating its intentions to its friends and partners abroad.

But in Arabia and the Gulf, the narrative of an America suspected of intending to pivot from the world’s most vital region to one of considerably less importance is cause for concern from one end of the GCC region to the other.

The very idea that the GCC countries’ paramount protector for the past four decades might possibly divert its focus strikes many in the GCC region as incredulous, particularly in light of the fact that for the past 27 years the United States has sent tens of thousands of armed forces to Arabia in support of regional security, defense, and stability but not once to Asia.

An America seen as partly credible and partly incredible simultaneously in an area such as the GCC region would be humorous were the matters at issue not so serious. For starters, one need only ponder the potential implications that an actual American pivot could have on Tehran-GCC, U.S.-GCC, and U.S.-Iranian relations. The fallout would likely have a worldwide negative impact on stock markets and financial investment institutions, threaten global security and stability, encourage Iranian assertiveness, revive the regional prospects for Al-Qaeda, and provide a boost to local extremist groups bent on overthrowing the GCC’s monarchies.

Viewed in this light, many wonder whether Washington is certain of the efficacy of the direction in which its foreign policies are headed.

This much is clear: the United States is indeed doing two seemingly contradictory things at once. ((That is, it has been taking steps, on one hand, to extend and strengthen its overall position and influence in Arabia and the Gulf. On the other, it has simultaneously been increasing the degree of its strategic focus and priorities towards Asia. Like the Arab poet and mystic Khalil Gibran was reported to have said, “In my staying, there is a leaving; in my departing, there is a remaining.” If judged only by appearances the United States would seemingly have the world believe it is concurrently doing both. Or as Kris Kristofferson said about Johnny Cash — that “he’s a walking contradiction, partly truth and partly fiction” — would also seem to fit the description of how some regard American policies the past few years towards not only Arabia and the Gulf, but also the Levant, the Fertile Crescent (i.e., Palestine, Jordan, Syria, and Iraq), the Nile Valley region, and Arab North Africa as well as Afghanistan. Unsurprisingly, to many the result has been confusing. It need not be. This essay attempts to explains why.)) Already, the consequence has been partly disheartening, partly frustrating, and partly a growing source of greater anger and disappointment towards U.S. foreign policies than already existed.

The Provenance of Strategic Ideas and Concepts

Making sense of the confusion requires, for reasons of space, focusing not so much on Asia but on the GCC region, which is where the uncertainty lies.

Doing so begs several questions. Does America have a strategy towards this region? If so, for how long has it existed? What is its nature and extent? And what are its conceptual origins and parameters?

Many in the GCC region believe what the United States is doing in Arabia and the Gulf is without a strategy. Others conclude that instead of a strategy, Washington, for the most part, has tended to offer ad hoc reactions and improvised responses to a disparate array of regional challenges.

There are some who claim that the focus and behavior of the Obama administration are issue-driven. Within this view is a consensus that the most important issues include maintaining an adequately produced, manageably priced, and effectively administered flow of oil from the region to international markets, keeping the Hormuz Strait open to unfettered maritime commerce, and stemming the influence and spread of violent ideologies. Added to these are myriad other issues having to do with Afghanistan, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Syria, Tunisia, Yemen, and Israel-Palestine.

The Asymmetry of Empathy and Understanding

This writer contends that Washington’s policies, positions, actions, and attitudes towards Arabia and the Gulf have all along been and remain grounded, in general, in strategic concepts that were:

- formulated and forged in the early years after World War Two;

- heightened following the abrogation of Britain’s last treaties of protection for Gulf countries in 1971;

- refined in the aftermath of the 1973-74 Arab oil embargo;

- reaffirmed and clarified by the Carter Doctrine, proclaimed in 1980, in response to the onset of the Iranian Revolution, the seizure of American diplomats as hostages in Tehran, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan – all in 1979 – which spurred the signing in January 1980 of an Oman-United States Access to Facilities Agreement; ((President Jimmy Carter, “The State of the Union Address Delivered Before a Joint Session of the Congress,” The American Presidency Project. January 23, 1980. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=33079.))

- militarized with the introduction in 1987 of U.S. naval forces into the Iran-Iraqi war zone to protect shipping bound to and from Kuwait (“Operation Ernest Will”); and

- strengthened as well as expanded in the wake of the Cold War’s demise in 1989-90, followed rapidly by the unprecedented signing of four separate U.S.-GCC country Defense Cooperation Agreements (DCAs) in the aftermath of the U.S.-led internationally concerted action to reverse Iraq’s 1990-1991 aggression against Kuwait.

The challenge of comprehending the roots of these considerations requires viewing the matter through the eyes of the strategy formulation’s participants and asking difficult and, certainly for some, controversial questions.

Has the United States sought to advance American interests and policy objectives in Arabia within the context of a strategic perspective? ((Ambassador Chas W. Freeman, Jr., Dr. William Quandt, Dr. Marwan Muasher, and Dr. John Duke Anthony, “U.S. Grand Strategy in the Middle East: Is There One?,” Middle East Policy Council 71st Capitol Hill Conference. January 16, 2013. http://www.mepc.org/hill-forums/us-grand-strategy-middle-east.)) Has Washington’s approach to the GCC countries been anchored in a strategic appreciation and net assessment of the GCC region? Unfortunately, any attempt to answer such questions from the U.S. side of the equation is hampered by the greater inability of the American side to understand the Arab side than the reverse. ((The reasons abound. For example, consider that a minimum of 300,000 GCC citizens have received all or part of their higher education in the United States. In contrast, the number of Americans who have graduated from GCC countries’ universities is next to negligible. Compounding the difficulty on the American side is not only matters pertaining to language, with millions of Arabs being fluent in English and only a tiny fraction of Americans being proficient in Arabic. It is also that, from 1975 to the present, there have been more American-trained PhDs in Saudi Arabia’s Cabinet than PhDs of any kind in the United States Cabinet, Supreme Court, Senate, and House of Representatives combined.))

Prolonging the 20th Century: The American Game Plan

The framework for America’s overall strategic analysis of Arabia and the Gulf was hammered out on the anvil of analytical prisms at a given point in time. By whatever standards America’s strategic approach to the GCC was reached, it remains as valid now as when its most recent formulation was conceptualized and consensually agreed to by U.S. policymakers in 1992, not long after the 1989-1990 implosion of the Soviet Union, the fall of the so-called Eastern Bloc, and the accompanying end of the decades-old international communist threat.

It is easy to forget the heady days of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Yet the strategic implications of the communist coffin being slammed shut spread quickly and reverberated far and wide. No less significant, the vertical consequences of interring the unrelenting effort led by Moscow to “bury” capitalism burrowed deeply into the dynamics of the surviving international systems of governments and politics.

To Washington, the result could hardly have been more favorable: the United States, for the first time in its history, had indisputably become the world’s preeminent power. The implications of the new reality were not lost on American officials tasked with charting the way forward.

America’s strategic planners were acutely aware that such an unparalleled moment could not possibly endure indefinitely. They recognized that the accumulated strategic advantages and economic gains, together with the privileges and benefits associated with what had been termed “the American Century,” could not be sustained for long absent the formulation and implementation of a sound, long-term, strategic vision.

The strategic analysts of the day were confident that this extraordinarily auspicious juncture in America’s history could be prolonged only if it were tethered to three phenomena: the availability of and access to adequately produced amounts of manageably priced hydrocarbon fuels; the assurance of sound planning and preparation; and, above all, the steady presence of a visionary and decisive American leadership.

Just as vital would be the aid of working partners with strategic geology and geography, economic clout, financial resources, and/or geopolitical weight. Additionally important would be the extent to which those partners’ assets, ambitions, and actions translated into their influence over issues and interests of importance to key foreign policy objectives within regional circles and major international organizations.

If there were any doubt among strategic planners that this was and would for some time remain America’s moment in Arabia, the Gulf, and the GCC region, the reasons would soon enough be clear. Dispelling any doubt was the extraordinary effectiveness of the American-led internationally concerted action in 1990-1991 that reversed Iraq’s aggression against Kuwait.

No other country could have led such a global assemblage of effective power to help restore to Kuwait what was noted earlier as vitally important to each and every one of the GCC countries and to each and every nation everywhere: namely their national sovereignty, political independence, territorial integrity, security, and stability. ((Dr. John Duke Anthony, “Twenty Years Ago Today,” National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations Website. February 28, 2011. http://ncusar.org/blog/2011/02/20-years-ago-today/.))

To American planners then in search of a recalibrated vision and mission, the plaintive pleas scrawled on the walls of the American Embassy in Kuwait after the country’s liberation – pleas that encapsulated the identical sentiments of its fellow GCC members – said everything: “America, don’t go home.”

A Vision For 2020

This was the context during the final months of the George H. W. Bush administration when then-U.S. Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney tasked Under-Secretary of Defense for Policy Paul Wolfowitz with drafting a long-term strategic plan that would ensure the United States in 2020 would still retain its position as the world’s only super power.

Not long after the plan’s drafting was underway, a Department of Defense representative asked this writer to critique the direction in which the plan was headed. Although not allowed to see the draft, I was informed that the analysts and writers responsible for drafting the new strategic approach had already reached a preliminary consensus and were relatively confident that the United States could meet its objectives.

The tentative conclusions were that the United States had no choice but to remain preeminent in five separate but interrelated fields of power: economy, finance, technology, military, and industry. The strategic implications of this realization were obvious and far-reaching. Regardless of the cost and toll on the American economy, the United States would need to maintain superiority in these categories paramount to maintaining its international position, power, and role.

Energy Holds the Key

Asked whether I thought any one single factor might be essential to all five categories, I said that energy was and would continue to be such a factor. Energy is the one commodity, more than any other over which human beings have varying degrees of control or influence, which not only fuels humanity’s health, defense, security, and material wellbeing but also drives the engines of the world’s economies. ((Michael Klare, The Race for What’s Left: The Global Scramble for the World’s Last Resources. New York: Picador, 2012. Robert Bryce, A Gusher of Lies. New York: PublicAffairs, 2008.))

The follow-up question of whether “Our energy or someone else’s?” seemed trickier and more difficult. However, after taking some time to ponder the implications of how I might respond, I answered “someone else’s.” In so doing, I added a caveat: “But only if, at all, possible and feasible – by which I mean not immorally, manipulatively, exploitatively, and/or at the expense of others’ legitimate needs and rights.”

The case for utilizing another’s oil rather than one’s own in the case of the United States, although perhaps not obvious at first glance, becomes clear upon closer analysis. Hydrocarbon fuels, especially those derived from petroleum, are finite and depleting and the proven degree to which America has these forms of energy is vastly less than that of others.

Add to this the facts that the production costs of America’s oil supplies continue to be much more expensive than the production costs of the GCC oil-producing countries, and the per unit production levels of GCC member-states’ oil wells are substantially higher than the production levels of American wells. ((Author’s interview with an American oil company executive, December 2013, Washington, DC.)) It is therefore clear that the world’s most adequately produced, manageably priced, and available proven hydrocarbon energy is located primarily not in the United States or Asia but in Arabia and the Gulf.

Also clear is that what could prevent the United States from reaching 2020 with its preeminent 1992 status intact, other than the defense and governmental stability issues and challenges discussed earlier, are America’s competitors. There is every reason to believe that Washington’s rivals in 1992 for global prominence in 2020 were in agreement then and now regarding the importance of these identical fields of activity. These fields are the ones in which they, too, would have little choice but to perform well in if they were to have any chance of mounting an effective challenge to the United States.

The foremost competitors then as now have been China and Russia. Others possibly able to mount a credible challenge over time include the heavily populated developing countries. Among these are Brazil and India, which even then had rapidly growing and increasingly energy-hungry economies.

A Look at the Scorecard

Where is the United States in terms of the strategic objectives it set out to achieve in 1992?

Without a doubt, the United States has remained the world’s most militarily powerful country. In addition, with a 16.2 trillion dollars GDP, America’s economy remains the world’s strongest – almost double that of its nearest rival, China. The global financial system, with the preeminence of the U.S. banking system, is still intact. ((Note that then-U.S. Deputy Treasury Secretary Robert Kimmitt visited four GCC capitals during the month of October 2008 immediately prior to the November elections. He was unsuccessful in his efforts to persuade these countries’ ministries of finance and sovereign wealth fund directors to infuse massive sums of funds into the failing American economy on the eve of the U.S. banking system-induced housing mortgages financial crisis. Characteristic of the failure, as one financial executive who sat in on one of the meetings informed this author, was that one of the Treasury Deputy’s most important Arab host said, “You Americans always expect us to be with you on your crash landing, and we have repeatedly done so. However, we have had enough. This time, we insist that the two of us be together on any future takeoff. Within only a few months after the inauguration of President Obama, it was not coincidental that the U.S. agreed to the formation of a new world economic grouping. Called “The Group of 20,” Saudi Arabia was included to represent the GCC countries. Author’s interview with an American financial and investment advisor to one of the GCC countries’ investment authorities. Washington, DC, October, 2008.))

As Americans recover from the U.S.-induced financial crisis that began in 2008, the American dollar continues to be the principal monetary instrument of exchange for most international business transactions. The U.S. strategic telecommunications, information, cyber, and transportation infrastructure within America’s industrial base have remained in place, and the ongoing prowess of the United States in intellectual property rights and patented technology is still supreme worldwide.

Thus, the strategic planners of 1992 have helped to ensure that the United States is well on its way to meeting the goals that were set for 2020. More particularly, up to this point in time, they have met the objectives they set with regard to the specific roles they expected Arabia and the Gulf to play in helping to prolong the unparalleled array of benefits associated with “the American Century.”

Simultaneously, the multifaceted Saudi Arabian-U.S. defense relationship and America’s defense cooperation and access-to-facilities agreements with the five other GCC members have thus far contributed mightily to America’s overall strategic goals as they pertain to Arabia and the Gulf. Indeed, the ongoing implementation of the agreements has arguably helped deter Iran from attacking and, for the most part, intimidating the GCC’s member-countries. ((Dr. Anthony H. Cordesman, “Securing the Gulf: Key Threats and Options for Enhanced Cooperation,” Center for Strategic & International Studies. February 19, 2013. http://csis.org/publication/securing-gulf-key-threats-and-options-enhanced-cooperation.))

Even the efforts by pro-Iranian dissidents to destabilize Bahrain, Kuwait, and to a lesser extent Saudi Arabia, have fizzled. Ironically, such efforts have achieved the opposite: a circling of the wagons by the countries affected. As a result, in addition to their opposition to the prospect of Iran ever obtaining a nuclear weapon, there is an overall greater sense of oneness among most of the member-states in their resolve to stand together against any possible Iranian challenge to the GCC region’s governmental status quo. ((Awad Mustafa, “GCC Announces a Joint Military Command,” Defense News. December 11, 2013. http://www.defensenews.com/article/20131211/DEFREG04/312110011/GCC-Announces-Joint-Military-Command.))

Even Oman’s outlier position and role, which finds the sultanate holding back from the northernmost GCC states’ standing with Saudi Arabia in favor of a closer political union among the members, has, for the most part, been finessed. Certainly, it has not deterred Sultan Qaboos from serving, to the benefit of all the GCC members and the world in general, as a silent but extraordinarily effective intermediary between Tehran and the P5+1 countries.

In his typical low-key and behind-the-scenes way, Qaboos has succeeded in helping the two sides find a mutually beneficial path forward towards placing Tehran’s relationships with the outside world, and especially the Great Powers if not also the GCC countries, on as solid and positive a footing as possible.

As roseate as all this may sound, America’s achievements in the five categories of measurable might and associated influence have not been free of cost. The accomplishments occurred in association with the contentious, heavy-handed, and at times brutal and illegal means employed by the United States. Putting aside for sake of analysis the allegations and documented confirmations of “unethical,” “hypocritical,” “opaque,” “unaccountable,” “double standard,” and “morally audacious” actions, together with its “violations of international law,” Washington has thus far succeeded in meeting the goals of the 1992 plan.

Analysts within the GCC region readily acknowledge that America’s strategic achievements and goals pertaining to this region remain intact, but they note that the achievement has hardly come cheap. It was accompanied by the expenditure of trillions of dollars. It occasioned the killing of a country and the undeniably horrific scale of sheer destruction in human lives produced by the American-led invasion and occupation of Iraq, which, combined with the earlier ruinous regime of international sanctions imposed by the United States and the entire United Nations membership upon the Iraqi government, resulted in the inestimable self-inflicted harm that continues to this day upon what had previously been the immense reservoir of goodwill towards America in the GCC region and beyond. ((Dr. John Duke Anthony, “Measuring the Iraq War ‘Accomplishments’ Through the Lens of Its Authors: A Preliminary Assessment,” Voltaire Institute International Axis for Peace Conference. Brussels, November 17, 2005. http://ncusar.org/pubs/2005/11/measuring-the-iraq-war-accomplishments/.))

Why Pivot From “Success”?

Leaving aside the negative aspects associated with America achieving thus far what it set out to accomplish, and with eight years remaining to reach the end game envisioned in 1992, why switch the focus to Asia, where the vicissitudes of international forces and variables are as yet unclear and the prospects for a level of success comparable to that achieved in Arabia and the Gulf would seem improbable if not doubtful?

Why, indeed, when the dynamics of the new and profoundly different region in terms of America’s necessities, apprehensions, and interests are nowhere nearly as in alignment as they have long been between the United States and the GCC countries? And why, given that Asia arguably can hardly compare to the GCC region in terms of its repeatedly proven vital strategic relevance and benefit?

None of this is meant to imply that the forces and factors propelling the reported shift in American strategic analysis and priorities are not understandable. They are. However, what is not being discussed, debated, and written about are the masked and questionable motives and the intended end games of those vocally promoting the pivot policy.

Overlooked Questions to Ask

Looking at possible motives and endgames for the “pivot mongers” brings up a host of additional questions.

Is there in play even a hint of inter-service rivalry among America’s uniformed armed forces? ((Author’s interview with a former Commanding General of U.S. Central Command, January 2014.))

Does the rationale for turning from Arabia to Asia have anything to do with the corporate bottom lines of the defense and aerospace sectors and future Congressional budgetary outlays for the country’s costly high-ticket navy and air force?

Are the dramatically shrunken defense budgets affecting the various military branches not at or near the root of what is prompting the alleged shift in strategic focus from the GCC region to Asia?

Is the mammoth arms manufacturing sector of the U.S aerospace and defense-related industrial base – and its important role in the American economy and as an employer of hundreds of thousands of Americans – not a major albeit largely unspoken factor behind this debate?

If the market for exporting arms to the GCC countries’ defense sectors is believed to be satiated for the foreseeable future, can one understand the logic of those whose livelihoods are dependent upon this sector doing what they can to devise seemingly plausible reasons for generating sales elsewhere?

Are Israel and its American supporters’ perennial strategy of deflecting international focus from its nonstop settlement of the Occupied Palestinian and Syrian territories in violation of international law not also helping to drive the emphasis on the need to pivot from Arabia to Asia?

And note that the Obama administration’s intention to conclude an Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement in the near term, with the implication that Israel would be required to agree to concessions it would rather avoid having to make. In this light, is it not in the strategic interest of Israel and its more ardent advocates to hype the allegedly growing greater global strategic importance of the India Ocean, playing up the fact that it is one of the world’s main maritime routes to and from the Asia-Pacific region? ((Robert Kaplan, Monsoon, The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power. New York: Random House, 2011.))

Why would America appear determined to embark upon a different, strategic, regional emphasis when doing so would appear to risk arousing deep and widespread suspicions of its true intentions in Asia?

Might a reason, as one keen analyst commented to this writer, be partly so as to be able to strengthen its capabilities to observe and, if need be, respond to future developments in the region? As an example, the analyst asked whether any country other than the United States could have responded as swiftly, massively, and effectively to the earthquake disaster in the Philippines in 2013. In answer to his own question, he said he doubted any could. ((Author’s interview with an American oil company executive, December 2013, Washington, DC.))

Is it in U.S. interests to awaken in America’s leaders and elites an unwarranted impending fear of Asia? Conversely, does the United States want to implant in Asia the perception of an American threat?

Does a U.S. government responsible for defending the United States and the legitimate interests of the 317 million American people want to provoke 1.4 billion Chinese? Might the Chinese understandably not look kindly upon a country or people that would give them reason to believe they were being needlessly antagonized?

Are the possibly coming trends and indications in the Asia-Pacific region likely to be of such a threatening nature and extent as various American fear-mongers and powerful interest groups would have the U.S. government, media, and general public believe?

Even if one’s analyses and assessments are confined to the realm of strategic thinking as opposed to acting, why would one contemplate so openly acting thusly at the expense of disappointing and frustrating one’s longstanding Arab strategic partners and allies? ((Dr. John Duke Anthony, “Saudi Arabian Ambassadors to America in Context: The Diplomatic and Geopolitical Lives of Ambassadors Prince Bandar, Prince Turki, and Adel Al-Jubeir,” National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations Website. December 5, 2011. http://ncusar.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/2011-12-05-Saudi-Arabia-Ambassadors-Context.pdf.))

Why do so, given the millions of Iraqis, Americans and others killed, wounded, and/or maimed for life in the wake of the still relatively recent U.S.-led invasion, occupation, and subsequent war in Iraq? And why do so amid the clouds of uncertainty attendant to the imminent steep drawdown of American forces from Afghanistan?

Consider also the following. Why do so in juxtaposition to and further avoidance of remedying the singularly ineffective record of the United States’ dealing justly, comprehensively, and effectively with regard to Israel-Palestine – perennially the longest, greatest, and most massive and pervasive issue fueling and fanning the flames of anti-Americanism and opposition to America’s allies, and American as well as Arab interests – all at the cost of inflicting yet another wound to the strategic international sextant of America’s moral compass?

In all of this, where’s the strategic merit in America’s reasoning?

Reasons for Oversight?

The fact that the American mainstream media have largely failed to examine and explain the questions, concerns, and issues raised and addressed herein – which should be a matter worthy of investigation – is shameless. Absent such an investigation the efficacy of the perceived pivot to Asia away from the GCC region would seem to stand unchallenged.

Can the media’s heavy dependence upon private sector advertisers, who are known to have strong emotional, ideological, and politically opinionated views and may stand to gain from a shift toward Asia, be the source of undue editorial influence and pressure in the pivot-to-Asia narrative that is being fed to the American public?

Is the tension and sometimes seemingly conspiratorial accusations on the Arab side regarding the “pivot” the result of American blindness and ignorance of how the U.S.-Arab relationship is viewed from its friends in Arabia and the Gulf?

Has America been negligent in how it has communicated with its Arab allies out of an inability to understand and appreciate their needs and concerns? Is this an instance of the proverbial “chickens coming home to roost” – where America has long neglected to consider the regional environment and do its utmost to assuage or abate the reasons for the legitimate anxieties of its Arab partners?

President Obama’s Upcoming Visit to the Kingdom

As President Obama prepares for his visit to Saudi Arabia, he would arguably do well to ponder the implications of, and have at the ready informed responses to, some of the questions and commentary posed herein. Certainly, the degree to which he is versed in advance regarding the challenges and consequences of the realities described and analyzed in this essay will be readily apparent to his hosts.

One thing for sure is that, for reasons deeply rooted in the manners, values, and principles of his hosts, his Saudi Arabian interlocutors will be extraordinarily polite and gracious in their welcoming of him and his entourage. They will also be certain not to bring up contentious issues for discussion or debate in the meetings that will take place. This, too, would be in keeping with the country’s history and its peoples’ culture, customs, and traditions handed down through the ages.

Even so, his hosts can be counted on to detect early on how seriously and effectively the president has been briefed on the issues to be discussed. This said, the fact that his visit signifies the importance that the president assigns to maintaining and where necessary remedying America’s relations with the Custodians of Islam’s holiest places will not be lost on the kingdom’s leaders or on the Saudi Arabian people, their GCC neighbors, and Arabs elsewhere. Nor will any effort he may make to reassure his hosts that the United States will not lessen its interests, attention, involvement in, and commitment to the GCC countries’ defense go unnoticed and unappreciated if it is deemed credible.

Neither will it be unrecognized that the president of the world’s most powerful country, in the manner of other American presidents before him, took time to travel to Saudi Arabia to convey his respect for an historic American Arab ally, friend, and strategic partner like no other.

He will have acknowledged in front of the entire world the extraordinarily influential position and role of a head of state and the leadership of a country that, again, like no other, possesses proven hydrocarbon reserves ten times that of America’s and has a land, air, and coastal mass greater than all of Western Europe combined.

He will have once more stood eye to eye with the leaders of a country more preeminent than those of any other Arab government within the earth’s most globally and regionally international organizations, e.g., among numerous others, the United Nations, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organization, the Organization of the Islamic Conference, the League of Arab States, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, and the Gulf Cooperation Council.

That the kingdom is the most prominent founding and activist Arab and Islamic member in these organizations is a fact of monumental moment in and of itself. If this reality and its impact on the entire GCC-U.S. relationship persuades the president and his entourage to pause and ponder the implications for America’s legitimate national interests of its not being itself a member of many of these international institutions, then this component of the itinerary, albeit but one part of the visit, will have succeeded.

Like nothing else, this segment of the president’s time meeting with his interlocutors in Riyadh will have sensitized him to the GCC region and its peoples’ cultures possibly to a greater extent than any other American president. It will have enhanced his awareness and appreciation of the exceptional burden the GCC countries bear not only for their citizens and inhabitants but also for peoples, issues, and challenges far beyond their borders.

The experience will undoubtedly heighten the president’s insight into the sheer weight and complexity of the GCC country leaders’ burdens. The insight will reveal that the burdens are not entirely unlike the weight and complexity of the ones he and his administration bear on behalf of the United States far beyond America’s borders.

If this chapter of President Obama’s in-country program proceeds smoothly, it will have introduced him to a keener and more empathetic identification with Riyadh’s vital positions and roles in institutions far afield. It will emphasize ever so subtly the reality that the meetings of such organizations are ones in which the United States is not represented but in which issues and interests of vital importance to Americans are regularly raised, addressed, and sometimes affected.

If on the other hand the visit is viewed as a failure, it will be seen as squandered and costly in the extreme. In the longer term, it will arguably be assessed as a hard-to-come-by missed opportunity. It will be deemed a time when Washington fiddled away a chance to mend fences and strengthen and expand America’s relations with the country whose leaders represent the legitimate needs and aspirations of nearly a quarter of humanity.

If the president will have done his homework in preparation for the visit, he will be acutely aware that many of the views of his hosts and those whose legitimate interests they seek to represent are in many ways at variance or in conflict with his views and those of other important and powerful American leaders. He will be also aware that the host and its allies and working partners have just as many interests if not more that correspond to and/or complement America’s than they have that the kingdom itself and its critics, opponents, and competitors view in an adversarial context.

The peoples whose security and stability are of considerable concern to President Obama and his hosts are numerous. Most are within, adjacent to, or near Saudi Arabia and the GCC region as a whole. They include the very ones listed in this essay: Afghanistan, Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, and Yemen.

At the end of the day, it is only natural that the president will want to do his utmost to represent and use his powers of persuasion in support and defense of America’s legitimate interests. And no one will gainsay that it is essential that he do so. But his being able to do this effectively will turn perhaps more than he knows on his ability and willingness to listen, not lecture, to learn, not try to teach, to appreciate, not pontificate, and, above all, to exhibit empathy, not hubris. Of this the regions’ peoples have seen too much. They have had enough and recoiled in disgust.

If this can be done, the symbolism alone – of a sincere and well-intentioned but domestically embattled American president like no other in the eyes of the world’s Arabs and Muslims – will be remembered positively long after the visit. His ability, as demonstrated in public address after public address to genuinely convey a tone of respect for another’s dignity, ideals, principles, and beliefs, will go far.

If the president can succeed in his mission, and most importantly – in contrast to his moving address to the Islamic world in his June 2009 speech in Cairo that was powerful and inspirational but afterwards came to little – if he will follow-up his rhetoric with deeds that match his words, this will do much. It will help to repair the broken reeds of what – even in its wounded status with an arrow through its heart, and even on the Valentine’s Day that is the anniversary of the historic meeting between American President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Saudi Arabian King ‘Abdalaziz bin ‘Abdalrahman Al Sa’ud on February 14, 1945 – is a relationship between two of the world’s most important countries, each preeminent and paramount in its own spheres of interest and influence, like no other two countries in the relationship between Americans and Arabs in modern history.

Conclusion

In the face of what lies ahead as the president prepares for his visit, reality brooks no illusion: the transition of a country’s strategic and foreign policy approach from one region to another under any circumstances is neither easy nor cost-free. Such things seldom are.

Certainly, this would be the case when considering a pivot from an existing overall effective American approach to one region toward another region where the alleged merits are questionable and debatable, the prospects dubious, and the potential implications and repercussions with regard to costs, rationale, efficacy, and necessity are serious and far-reaching.

In this particular instance, it is difficult to imagine how it would be wise for the United States to imply it is pivoting from an area that is far more strategically vital globally than the Asian countries are or could realistically hope to become in the immediately foreseeable future.

And why contemplate such a measure if in doing so it is bound to showcase for all the world to see one’s lack of empathy with regional considerations, and its very process is practically guaranteed to antagonize and frustrate one’s strategic partners and in-region allies?

Doing so without adequate explanation and context would certainly make no sense at all to America’s strategic friends – and foes, too – whose leaders would trade places with the United States in a second were it seriously to contemplate pivoting from the GCC region to Asia, let alone actually do so.

Dr. John Duke Anthony is the Founding President and Chief Executive Officer of the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations. In 2000, on the occasion of Moroccan King Muhammad VI’s first official visit to the United States, the king knighted Dr. Anthony, bestowing upon him the Order of Ouissam Alaouite, Morocco’s highest award for excellence. The only American to have been invited to attend each of the GCC’s Ministerial and Heads of State Summits since the GCC’s inception in 1981, he is a member of the United States Department of State Advisory Committee on International Economic Policy and its Subcommittee on Sanctions.

For more information access the National Council’s website: ncusar.org.

Read more from Dr. Anthony at: ncusar.org/pubs.