By Joshua Yaphe and Jaafar Altaie

Download as PDF: English | عربی AR

Published in partnership with the King Faisal Center on Research and Islamic Studies.

The views and opinions presented here are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the United States Government, the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations, or the King Faisal Center on Research and Islamic Studies.

Summary

Prime Minister Mustapha al-Kadhimi faces the same challenges that brought down his predecessor, Adel Abdul Mahdi – street protests, a flagging economy, and entrenched political elites. Most of his predecessors were willing to sacrifice one of these three goals for the sake of the other two, as long as the opposition remained divided and external support was forthcoming. Numerous commentators are ready to write off Kadhimi.[1] And there are good reasons to think his failure is inevitable, with Iraq doomed to a prolonged future of either political chaos or authoritarian rule. In either instance, there is also the near certainty of continued intervention by regional and international powers, contributing to insecurity and instability. The accumulation of almost two decades of grievances since the 2003 invasion, the repeated failures to keep pace with job creation and service provision, and the knock-on effects of the coronavirus pandemic are challenges that will certainly not be overcome in the next ten months. And there will undoubtedly be an extended period of political malaise in Baghdad as factions prove unable to compromise on an alternative to Kadhimi. However, Kadhimi has a real chance to win the elections now set for June 6, 2021, and even come out with a mandate for real reform. It would be wrong to write him off yet.

Popular Anger and Political Stagnation

On November 30, 2019, following weeks of protests in which government forces opened fire on the crowds, Adel Abdul Mahdi resigned as Prime Minister, opening up five months of wrangling over his successor. In that time, former Minister of Communications Mohammed Tawfik al-Allawi tried and failed to form a cabinet, Abdul Mahdi returned to office briefly, and Intelligence Chief Mustapha al-Kadhimi finally assumed the position on May 7. It would be another two months before he could finally appoint some of the most important ministerial portfolios, including Oil, Justice, Foreign Affairs, Agriculture and Trade. This was not a government formation process backed with confidence by a consensus or even a majority of political factions. Rather, it was multiple rounds of entrenched political elites trying to gain the upper hand on one another, only to realize that no single party has a crucial advantage over the others and none of the foreign powers have sufficient influence to sway the rest. Kadhimi was a compromise candidate among compromise candidates.

That is not to say that he is not skilled enough or qualified for the post. In many ways, he is more capable and experienced than many of his predecessors, if only by virtue of his steady management of the intelligence services. Most notably, though, he has proven himself capable of assuaging the concerns of Iran, the United States and Saudi Arabia. He was able to gain Iran’s acceptance of his appointment, even after taking the lead in Iraq’s outreach to Saudi Arabia over the past two years. That’s a remarkable feat of pragmatism. His political weakness does not come from any personal traits but rather from structural constraints that are much bigger than a single person. The system itself in Iraq is broken and cannot be fixed.

Kadhimi was a compromise candidate among compromise candidates.

In turn, Kadhimi has focused on the challenges and put forward an ambitious and coherent plan for reform. Immediately after taking office, Kadhimi announced that he would launch an investigation into the killing of protesters last fall and promised to release demonstrators held in prison since then, which provoked a sharp backlash from the Hadi al-Amiri’s Fatah Alliance and Muqtada al-Sadr’s Sairoun.[2] At the same time, Kadhimi finalized a deal to take four Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF, hashid al-sha’abi) units previously under the spiritual guidance of Iraqi Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani and move them under the direct control of the Prime Minister’s Office.[3] The effort was one of increasing state control over the militias, as Kadhimi went on to say: “no group or force has the right to be outside of the framework of the state.”[4] He has promised an end to civil servants receiving multiple salaries for overlapping duties, and in June a spokesman revealed that, “there is a specialized committee that will work to find and detect double salaries in all government organizations.”[5]

In early July, he replaced several senior-ranked security officials, installing Qasim Muhammad Jalal al-Araji as National Security Advisor and Abdulghani Ajil Taher al-Asadi as managing head of the National Security Agency.[6] He moved former National Security Advisor Faleh al-Fayadh over to become Chairman of the Popular Mobilization Forces (hashid al-sha’abi) with an executive order that specifically laid out the Prime Minister’s supreme control of the armed forces, “according to the constitution and the legislation in force.”[7] Kadhimi has repeatedly tried to speak directly to the people, committing himself to addressing public grievances and calling on youth to take politics into their own hands.[8] On May 18, Kadhimi published an editorial in several newspapers essentially admitting that he cannot overcome the complete lack of economic diversification, widespread corruption, crippling levels of unemployment, and massive capital flight, unless common, everyday Iraqis band together and rise above party politics.[9] That was a promise to hold new elections, and as with so many other promises, he has set his sights on moving forward with fulfilling that pledge whether or not other political elites in Baghdad are ready for it.

National Reconciliation

If this were 15 years ago, we would have spoken of political reform in Iraq in terms of “national reconciliation.” That meant different things to different people, such as ending the extreme process of de-Ba’athification that was instituted under Paul Bremer during his tenure as Administrator of the Coalition Provisional Authority, so that educated and qualified Sunnis could return to work. It meant forging a cross-sectarian political coalition that might reduce the public’s fears of random violence. But above all, it meant forging a sense of national identity and belonging for all Iraqis that would be directed at the state and the nation, rather than a sect, ethnicity, tribe or neighborhood. At least, that was the implied outcome of all those other definitions combined.

The growth of the mainline Islamist parties, their spillover into non-state militias, and their attachments to foreign entities all ran counter to that project. The Islamic Supreme council of Iraq, Da’wa, Tawafuq, Fadhila and the Sadrists were all successful political forces in the 2000s, precisely because they were able to provide services, mobilize followers and control the message in their localities. At a time when the country was in chaos, these political organizations helped locals in their neighborhoods to understand what was going on elsewhere, what they should think about it all, and how they were expected to react.[10] These parties created imagined communities for their followers, where some small fragment of stability and normalcy could be experienced. That process created terms of reference for defining proper behavior, with rewards in terms of patronage and collective punishment by the community for stepping outside the lines.

However, that kind of political activity is a Ponzi scheme. The only way to keep growing a loyal following is by handing out more favors and preaching more divisive rhetoric. That requires more control over line ministries with access to resources and more public spectacles demonstrating the will to back up rhetoric with the use of force. The initial ideological impetus for all this activity was the brutal regime of Saddam Hussein and his legacy of torture and oppression, but a majority of Iraqis today are too young to remember much about that era or they weren’t even born then. The militias have come to fill that ideological vacuum, coalescing into the PMFs that were launched to defeat the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria after it took over Mosul in June 2014 and threatened the outskirts of Baghdad. The PMFs presented a carefully cultivated media image of success and adventure, pride and honor, in pursuit of security and safety. They also completed the path first marked out in 2003 of armed non-state actors achieving large-scale popular followings in service to the state, though crucially not fully controlled by the state.

This situation is not unusual. There is not one single path to security and virtually no one state can claim a complete monopoly on the use of force. Moreover, the relationship of governments to non-state actors typically evolves over time to meet the current needs of the day.[11] However, in the case of Iraq, what was sacrificed in the process of finding political expediency for the chronic problem of insecurity was the notion of a national identity and loyalty to the state. The need for a national reconciliation project that was so prevalent in the mid-2000s might have subsided due to intervening factors like the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and anti-corruption protests, but that does not mean it was accomplished. Kadhimi cannot expect to receive any support from the mainline political parties in Baghdad, any shaming of them in the media will only make them defensive, and any attempt to cut off their revenue streams will provoke a backlash. Yet fiscal problems due to sustained low oil prices, compounded by the economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic, will increasingly force him to move in directions that require strong, broad-based political support.

Economic Pressures

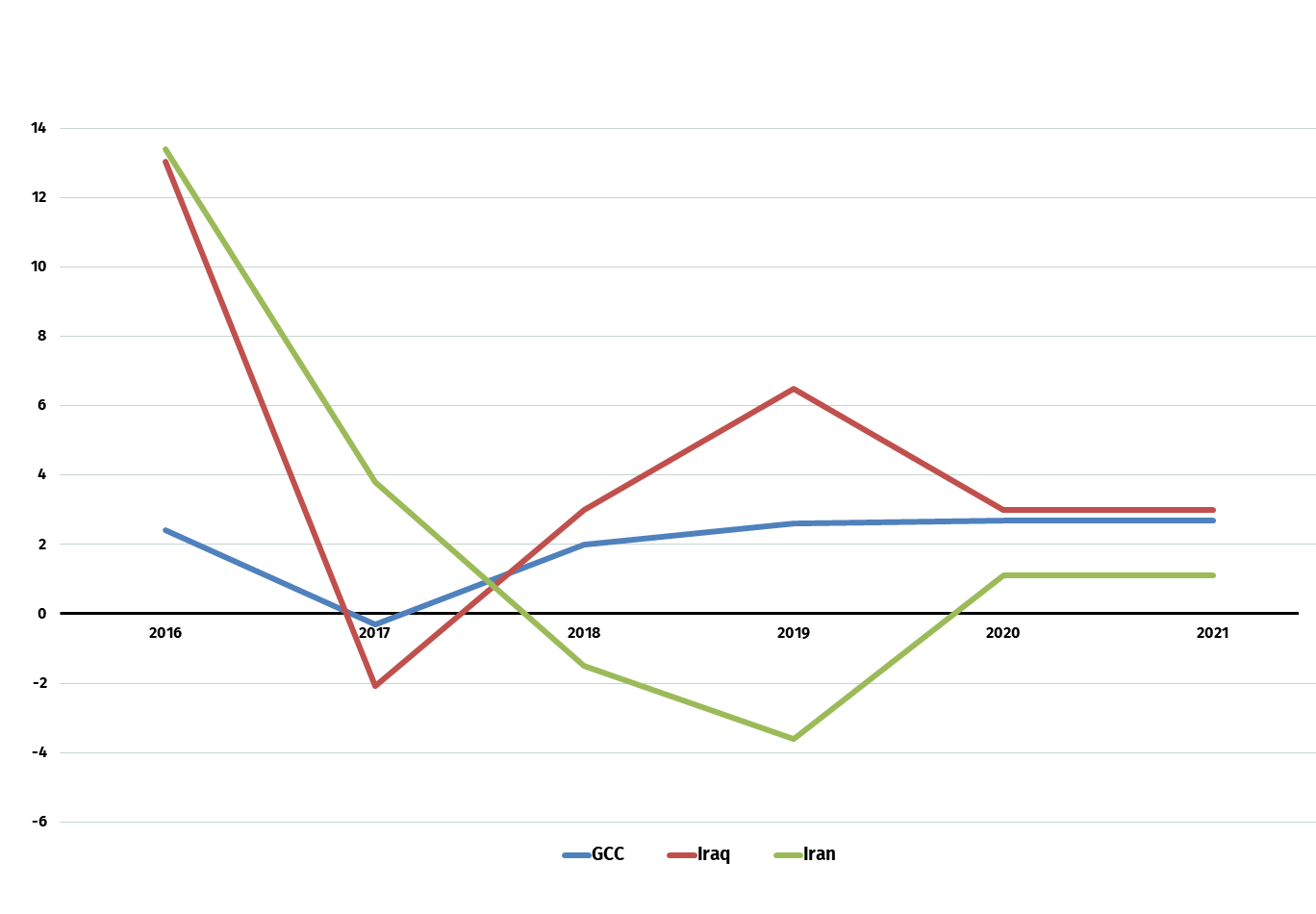

Iraq’s economy has been on a consistent growth trajectory since 2003 driven mainly by the hydrocarbon sector. This is in spite of the country’s persistent political instability and insecurity, and economic shocks that were largely the result of international oil price volatility.

An age-old maxim is that capital refuses to go where a country’s near or long-term situation is not assured, especially with regard to security, stability and return on investment. In Iraq, non-oil Foreign Direct Investment has virtually collapsed since 2016, despite rising public demand for goods and services, meaning that the government faces tough challenges in improving marketplace attractiveness. More importantly, it implies that economic growth in the near term will have to come from investment in the oil and gas sectors, which is a significant problem given the persistent slump in global oil prices and weak demand due to the global economic downturn.

By April, as the economic impact of the coronavirus set in and it became clear oil prices would not immediately bounce back, Iraq’s oil revenues slumped to their lowest level in in over a decade. While the government sold 3.4 million barrels per day, it only earned $1.4 billion.[12] Some countries like Kuwait have accumulated sizeable reserve funds and sovereign investment vehicles that can weather economic and financial storms, while others like Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar have large-scale development projects they can delay or cancel. But states like Iraq that depend on oil revenues for over 90 percent of government income, with extensive public sector payrolls and political patronage networks to fund, are especially vulnerable. Press reports in May claimed that accumulated revenues had only reached around $5 billion of the $12 billion that were needed to fund government salaries and other core obligations.[13] While the government is attempting to maintain its payroll obligations, in June it lowered pensions and proposed reductions to state salaries, creating a public uproar and prompting the parliament to vote against any salary cuts.[14] As a result, it is hard to see how the government can improve the overall fiscal situation absent either a dramatic up-swing in the price of oil or direct infusions of cash from other countries, neither of which is likely to happen. Foreign assistance was the first budget item Saudi Arabia cut in the global economic downswings of the mid-1980s and early 1990s, and certainly the top priority for the each of the GCC states right now has to be stabilizing their own domestic economies.

How much longer?

It is this worsening economic situation that will keep Iraqi protesters in the streets, even as they express a wide range of demands and maintain high expectations for speedy results.[15] And protests are likely to expand and become increasingly violent throughout the fall, as the government faces difficult decisions about whether to trim the public sector budget in payroll or expenditures for services. Just as in America, London, Paris and Hong Kong, the coronavirus does not appear to be stopping Iraqi demonstrators from turning out on the streets, and just like last fall, there are already protestor injuries and deaths.[16] Iraqi politicians would be wrong to think that limiting Kadhimi’s authority is in their best interests. Kadhimi can be replaced, but the previous round of cabinet formation negotiations last winter proved that no one faction holds sufficient sway over the others to impose its selection. Similarly, the recent negotiations that produced this cabinet proved that Iran does not currently have the ability to bring the various factions in line with its will in any clear and determinate way. Neither can the United States be ousted from the country as Iran might like, especially since some key populist figures like Muqtada al-Sadr continue to benefit politically from the ongoing U.S.-Iran tensions. In addition, the failure of the Kurdish independence referendum in 2018 exposed deep divisions among the Kurdish political groups that other domestic and regional actors have exploited ever since.

In that sense, the political gridlock in Baghdad is both to Kadhimi’s detriment and to his advantage in stabilizing the country. All of the dominant political movements in Iraq are experiencing fragmentation and division. Sectarian entrepreneurs are at their lowest point since the invasion, as the reality emerges that politics on a sectarian basis lacks credible answers for problems such as how to structure a functioning economy and how to construct a more pragmatic geopolitical strategy with that functional interaction and a mutuality of benefit between Iraq and its neighbors. The utter failure of sectarian politics presents clear opportunities for reforms that point towards a more federal and inclusive political system.

The political gridlock in Baghdad is both to Kadhimi’s detriment and to his advantage in stabilizing the country.

An economic reform program should take precedence and priority in such a strategy. The immediate aim is to implement the most realistic cost-cutting program and secure sufficient external pledges of economic assistance to enable Iraq to meet its immediate current account expenditures without depleting its foreign reserves. A subsequent phase of the program must address how quickly Iraq can again become economically self-sustaining. To this end, the country needs a fast track plan for how Iraq’s national-level overhead expenses can operate on a lower fiscal break-even oil price reflective of current market realities. Diversifying away from Iranian gas imports, which provide a quarter of Iraq’s gas consumption, will be difficult given that the cost of producing power from Iranian gas is far lower than Iraq burning its own crude or distillates.[17] But it is a key step that can have major benefits not only in the long-term but in the short-term as well. The goal here is the same as it is with all sectors of the economy – demonstrate to the international oil companies that the country’s barriers to Western investment are decreasing. A more U.S.-centric outlook projects an image that Baghdad is not merely trying to squeeze the majors for every penny of royalties and fees, while running to Iran for assistance whenever the macroeconomic situation starts to look bleak. Even if it means giving up some benefits today, Iraq would appear to be better off in the long run with committed Western firms that have a 15 to 20-year investment horizon in mind.

Above all, Kadhimi must have the resolve and external assistance from its present strategic partners to bolster confidence in his supporters that his reforms can be sustained and protected, even while acknowledging the harsh realities. That kind of honesty may be political suicide in many parts of the world, but it can also be an electoral strength. The public can see that he is meeting with international allies and getting out in front of the camera, rather than hiding behind his desk and letting spokespersons advance his message, even if he hasn’t fully lined up the requisite political support for his next move. It will also mean setting targets for improvement in areas like job creation and skills training, even if they are initially modest and realistic. Projecting that level of confidence might buy Kadhimi some time with a limited reprieve from protestors in the streets, before the temperatures begin to recede and protests start to ramp up again in the fall. The rest is up to the political factions in Baghdad. If their indecision and failure to reach compromise on an alternative continues through the spring of 2021, as is likely, it will confirm that their relevance is far more limited than they and their supporters would care to admit. And if Kadhimi chooses to run again, he might just be able to convey the successful image of a political outsider, an underdog and a survivor.

![]()

[1] Bobby Ghosh, “Early Elections Won’t Save Iraq’s Prime Minister,” Bloomberg, 4 August 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/amp/opinion/articles/2020-08-04/early-elections-won-t-save-iraq-s-prime-minister

[2] “al-Fatah bi-ri’asah Hadi al-‘Amiri wa Sa’iroun bi-ri’asah Muqtada al-Sadr t’ahidta li-‘Adil ‘Abd al-Mahdi bi-‘adm musa’lata ‘an qatil https://aliraqnet.net/الفتح-برئاسة-هادي-العامري-وسائرون-برئ

[3] Omar Ahmed, “Pro-Sistani factions leave Shia forces, but Iraq’s PM signals they are here to stay,” Middle East Monitor, 18 May 2020, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20200518-pro-sistani-factions-leave-shia-forces-but-iraqs-pm-signals-they-are-here-to-stay/amp/

[4] “al-Kadhimi: ‘la quwah min haquha an takun kharij itar al-dawla,” Rudaw, 28 May 2020, https://www.rudaw.net/arabic/middleeast/iraq/280520208-amp

[5] “The Office of Kadhimi: There are 18,000 individuals who have double salaries in the Ministry of Education,” al-Sumaria, 23 June 2020, https://www.alsumaria.tv/news/محليات/349435/مكتب-الكاظمي-هنالك-18-الف-شخص-من-مزدوجي-الرواتب-في

[6] “Documented… al-Araji is the National Security Advisor,” ‘Ain al-Anba’, 13 July 2020, https://www.eye-n.com/index.php/permalink/214331.html

[7] “Its official… the appointment of al-Fayyadh as Chairman of the Popular Mobilization Forces (document),” Shafaaq News, 16 July 2020, https://shafaaq.com/ar/أمـن/رسميا-تعيين-الفياض-رئيسا-لهيئة-الحشد-الشعبي-وثيقة

[8] Louisa Loveluck, “Iraq’s prime minister announces early elections, which will be held next year,” The Washington Post, 31 July 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/iraqs-prime-minister-announces-early-elections-which-will-be-held-next-year/2020/07/31/7075a272-d34a-11ea-826b-cc394d824e35_story.html

[9] “The text of the article of the Prime Minister, Mustafa al-Kadhimi, which was published today in several Iraqi newspapers…” 18 May 2020, http://www.ashurnews.com/نص-مقال-رئيس-مجلس-الوزراء-السيد-مصطفى-ا

[10] David Siddhartha Patel, Islam, Information and Social Order: The Strategic Role of Religion in Muslim Societies, (Ph.D. diss., Stanford University, 2007).

[11] Ariel Ahram, Proxy Warriors: The Rise and Fall of State-Sponsored Militias, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011).

[12] Ben Van Heuvelen and Ben Lando, “Oil revenues crash, dragging Iraq deeper into crisis,” Iraq Oil Report, 2 May 2020, https://www.iraqoilreport.com/news/oil-revenues-crash-dragging-iraq-deeper-into-crisis-42701/

[13] “Iraqi government breathes a sign of relief as it secures another month of salaries,” The Arab Weekly, 27 May 2020, https://www.thearabweekly.com/iraqi-government-breathes-sigh-relief-it-secures-pay-salaries

[14] Ammar Karim, “In Iraq, public outrage over austerity stymies reform plan,” AFP News, 16 June 2020, https://www.barrons.com/news/in-iraq-public-outrage-over-austerity-stymies-reform-plan-01592366409

[15] “Leave Kadhimi… Boiling over in the streets and an imminent return to a flood of revolt awaiting the zero hour,” The Baghdad Post, 26 July 2020, https://m.thebaghdadpost.com/ar/Story/199094/ارحل-يا-كاظمي-غليان-في-الشارع-وعودة-وشيكة-لطوفان-الثورة-تنتظر-ساعة-الصفر

[16] Hassan Ali Ahmed, “Iraqi protests resume as new government builds support for reform,” Al-Monitor, 21 May 2020, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2020/05/iraq-kadimi-protests.amp.html

[17] Majed Al Suwailem, Saleh Al Muhanna and Rami Shabaneh, “U.S.-Iran Tensions and the Waiver Renewal for Iranian Gas Exports to Iraq,” King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center, 21 January 2020, https://www.kapsarc.org/research/publications/u-s-iran-tensions-and-the-waiver-renewal-for-iranian-gas-exports-to-iraq

![]()

Mr. Joshua Yaphe is a Scholar-in-Residence at the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations and an Associate Fellow at the King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies.

Mr. Jaafar Altaie is Managing Director of Manaar Energy Consulting (Manaarco) and former Economic Advisor to the Iraqi Ministry of Oil.

Author

-

Mr. Joshua Yaphe is a Scholar-in-Residence at the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations. He has served as an Analyst for Arabian Peninsula Affairs at the U.S. Department of State. In that role, he briefed policymakers, conducted research, hosted conferences, and helped serve as a resource for diplomats in Washington and around the globe. Mr. Yaphe is currently a Ph.D. candidate preparing a thesis on the history of Saudi Arabia.