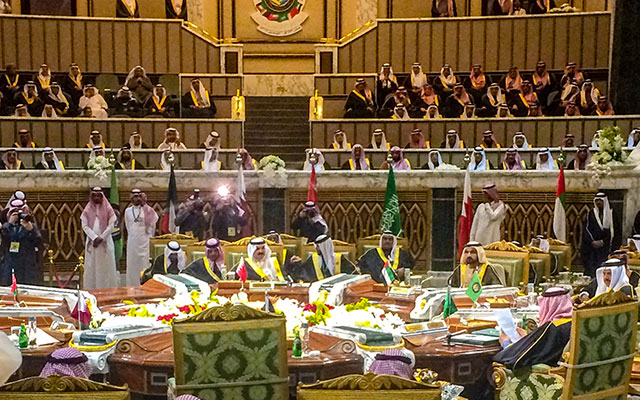

Today, the 40th summit gathering of the Gulf Cooperation Council’s Supreme Council is taking place in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Founding President and CEO of the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations, Dr. John Duke Anthony, is attending as an observer. He is doing so as The Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, presides over the meeting of Gulf leaders and/or their chief representatives.

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) was formally established in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi on 25 May 1981, at a summit that this writer was privileged to attend, as he has attended every GCC Summit since. An Arab sub-regional organization that represents some of the world’s wealthiest per capita countries in a geographical swath lining the length of the western coast of the Gulf, the GCC region encompasses what is arguably the most strategically vital area on the planet. The GCC’s six member-states are Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. In addition to all five of the member-states being a landward neighbor to Saudi Arabia, all six share maritime borders with the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Location of the Summit

This 40th GCC Heads of State Summit is the first time the summit has been held in the same location (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia) in two consecutive years. Observers differ regarding the reason. Some believe it is a testament to the effectiveness and importance of the GCC Secretariat that, from the organization’s inception in 1981, has been headquartered in Riyadh. Others hold to the view that the repeated focus on having Riyadh host the annual summits is but an echo of the United Nations, whose annual General Assembly Meetings are held in New York.

Still others wish to accustom the member-states to meeting in Riyadh rather than a succession of other GCC capitals, as has been the practice for most of the organization’s existence. Among military analysts, an unstated reason is the strategic geographic depth associated with Riyadh’s location deep in Arabia’s interior. Among the other members, only Oman offers comparable strategic depth necessary to withstand an invasion from across the Gulf. In contrast, focus one’s lens on the four other members. Given their location on the coast, what becomes readily apparent is how precariously situated each would be to a potential future aerial or amphibious attack by Iran, which lies but minutes away.

Other reasons have also been offered as to why this year’s Summit, like last year’s, will be held in Riyadh. Keep in mind that the venues for the GCC’s first 38 summits were held in rotational fashion in a given country one year, another the next, and another the year after that, and so on.

That prior practice had multiple merits. It allowed each of the GCC members to showcase their capital. This was important in a situation where, when the GCC began, not all of the GCC’s citizens had visited each of the other five members’ countries, let alone on multiple occasions. Additionally, the sheer act of getting ready for visitations by dignitaries from five of their fellow states provided stimuli to each host country to spruce up its capital environs.

Over time, a result was that large numbers from all six GCC countries became familiar with, and relatively comfortable in, one another’s country. This was in keeping with what some of the founders envisioned. Given the pioneering experiment in regional cooperation that the GCC has represented from the start, this result was no small feat. Aiding the sense of enhanced togetherness has been the separate passport and visa lines reserved for use by GCC citizens only in each of the members’ airports.

Cost-Benefit Analyses

The efforts at cooperation have fostered what would undoubtedly have taken far longer to inculcate otherwise: a sense of GCC oneness, if mainly at the level of the citizenries and if not always to the same extent among some of the elites.

Yet, with progress made toward the objective, it was inevitable that the question of costs would become a concern. For the four wealthiest GCC countries – Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates – the expense of hosting the others was manageable. For Bahrain and Oman, however, the necessary financial outlay had undoubtedly become a strain. It might have prompted consideration of whether the rotational system of hosting the summit was any longer worth the expense.

To their credit, neither Bahrain nor Oman is known to have publicly called into question the value of rotational hosting from an economic perspective. Yet several years ago, the other four members, aware that these two countries could use a helping hand, provided just that. In a philanthropic act to allay the financial circumstances of their fellow members, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE agreed to contribute a billion dollars annually to Bahrain and Oman each, spread out over a ten-year period.

Yet, if the latter reason might somewhat explain why Oman forewent having the summit in its capital city of Muscat when it was its turn last year, it would not explain why Abu Dhabi opted to pass on hosting this year’s Summit. In the absence of a stated reason by the UAE government, one is left to speculation.

Viewing the situation in this context, some have guessed that the reason has to do with Abu Dhabi not relishing the idea of hosting a delegation of Qatar’s senior leaders, at least not yet. If so, passing the baton to Riyadh could be a way of not having to experience a degree of discomfort that its leaders, and significant sectors of the UAE public, would at this juncture prefer to forego.

Current Realities

With this as background, what does the current situation say about the GCC? For starters, it is impossible to deny that most of the mainstream media have tended to argue that the GCC is finished, it is irreparably weak, and/or its previous sense of unified oneness is irrevocably damaged. Over and against these obituary-sounding pronouncements is a different picture.

Consider the member-states’ formidable array of support to Iraq during the eight year 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War. Consider their unified stance against Iraq’s 1990-1991 invasion and occupation of Kuwait. Consider how, throughout the 1979-1989 Soviet Union (USSR) invasion and occupation of Afghanistan, they worked in lockstep with one another in association with the major Western powers to help drive the final nail into the coffin of the Red Army and thereby help precipitate the implosion of the USSR not long thereafter. Consider also their working together successfully, from 1979 to the present, to deter the spread of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s revolution to their countries.

By any standard, these are no small feats. Admittedly, to give critics their due, three of the four successes enumerated appear, metaphorically, more in the rear view mirror than through the front windshield of the nearer term present. Critics might ask: what of late has the GCC done that is worth noting?

The answer in two words is numerous things. A caveat is: just because one has not read or heard of such phenomena does not mean they did not occur. Through it’s nearly four decades of existence, the GCC has achieved and continues to pursue many very real and beneficial successes in economic, environmental, legal, political, security, and strategic realms.

Consider, for example, that the GCC Secretariat holds a minimum of 400 meetings per year that include representatives of all six member-states. In some years, the number is closer to 700. If this is not an indication of how seriously all six of the members regard the GCC experiment it would be hard to know what would. The GCC’s work is continual and ongoing, while often the attention paid to the organization is only periodic and tied to meetings of its heads of state.

Another caveat is: beware the viewpoints of observers whose perspectives are clouded. The reference is to the hitherto unprecedented so-called “rift” involving the GCC countries. To wit: since June 2017, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE have cut relations with and severed all transportation routes between themselves and Qatar.

The Rift

The three GCC countries that have been isolating Qatar for the past two and a half years have so far made only modest public moves toward ending the crisis. Absent any renunciation of the demands issued in the early months after relations were severed, it is difficult to see how or when the path towards full reconciliation might be opened.

From the foregoing, is one to infer that there has been no thaw in the relations between the boycotting countries and Qatar? If one were to rely mainly on the Western media, the answer would be yes.

Nearer to hand in the region itself, a sign of how badly many wish to see the row ended is the degree to which various regional media highlight almost any perceivable shift in the standoff. Examples are not hard to find. In recent days, the fact that all three of the boycotting countries traveled to Doha, Qatar’s capital, for the Arabian Gulf Cup football tournament was cited as such an indication. Sports, since ancient Grecian times, have often had a palliative effect among adversaries.

Whether the recent coming together in Doha will translate into an effective reconciliation among the countries’ leaders is something that is altogether different. For evidence, some will look no further than yesterday, when at the GCC’s Annual Ministerial Meeting, comprised of the six countries’ foreign ministers, Qatar’s Foreign Minister, H.E. Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al-Thani, was absent.

The dashed hopes in this context were weighed against the fact that the Minister had reportedly visited Saudi Arabia in recent weeks in an apparent bid to at least open a dialogue aimed towards closing GCC ranks going forward. They were measured also against the fact that summit host, King Salman of Saudi Arabia, had issued a personal invitation to Qatar’s Amir, HH Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad Bin Khalifa Al Thani, to attend this year’s Summit.

Which Way to Read the Tea Leaves?

Those who pinned their hopes on the King’s invitation overlook that the same King issued an invitation to the same Amir last year, and yet the Amir absented himself. This writer, who is here for the Summit meetings, would be surprised if the Amir attends. He will not be surprised if he does not. A reason is that, at best, one can perceive only a partial reconciliation in the offing. For a greater one, far more diplomatic groundwork than has occurred of late would be necessary.

Those expecting the opposite overlook the fact that seldom has a GCC summit of any kind signaled a major breakthrough of a logjam among the leaders. By their own preference, the rulers are opposed to declaring such momentous resolutions at a summit when every journalist has their pen poised and every photographer has camera in hand ready to record the event for posterity.

Counter-Intuitive Analyses

It is wise not to read too much into the prospects for an early reconciliation of what, after all, has been a stream of mutually incriminating invective hurled back and forth between the disputants. Instead, one must look elsewhere for movement of a different kind that is headed in the desired direction. Here, the evidence abounds of all six GCC countries putting aside whatever differences they harbor in order to come together for meetings, exercises, and events in which all six have a stake and each seeks to benefit.

Not the least of these examples are the armed forces maneuvers involving all six GCC countries. Another has had to do with their coming together to forge more effective countermeasures in the fight against extremists. This writer can attest personally to these kinds of pan-GCC cooperation phenomena, for he was recently asked to address one of them.

In addition are the continuing rounds of meetings between the United States and all six GCC countries’ representatives. The reference is to the strategic dialogues that have been forthcoming and ongoing for quite some time. All six GCC countries’ representatives participate side by side with one another in forums like these, too.

Moreover, last May, high-level representatives of all six countries met in Makkah to compare notes on the attacks attributed to Iran against oil tankers belonging to one or more GCC countries this past spring. The May 2019 GCC Emergency Summit in Makkah was called under Article II of the GCC Joint Defense Agreement, which was concluded in 2000 and ratified by all member-states.

Looking further ahead, the clock is ticking between now and the 2022 FIFA World Cup football tournament in Qatar. It is a foregone consensus among GCC watchers here on the ground that the single largest number of spectators for the games in Qatar will be Saudi Arabians. With the love for football encompassing Bahrain and the UAE as well, it is next to impossible to imagine the games occurring in Qatar with no Bahraini or UAE fans in the stands.

This writer has no doubt that the GCC as an organization will survive the current dispute among its members. The Summit that begins within hours might be reckoned as proof positive.

A Passing of the Baton

One thing that happens in every GCC summit is hardly the stuff of dramatic headlines. It has to do with the heads of state mulling over the annual reports submitted to them for their review and approval by the GCC’s Secretary-General on behalf of the Secretariat. What makes this year’s Summit different than the preceding eight ones is that there will soon be a change in the Secretary-General. H.E. Dr. Abdullatiff Bin Rashid Al Zayani has held the post now for three consecutive three-year terms.

Of no small import, Dr. Al Zayani penned in recent weeks an outstanding essay, “The Road of Interdependence.” The National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations was privileged to publish the essay. Dr. Al Zayani’s analysis of regional trends takes its cue in part from the success of European integration after two wars in the first half of the Twentieth Century. As Europe’s collective efforts have built and sustained a firm foundation for collaboration at many different levels, war among them has been avoided for the past seventy years. In its place there exists a solid basis for mutually beneficial cooperation among the different countries.

At yesterday’s meeting of the GCC’s Ministerial Council, the organization’s principal policy recommending body, the appointment of a new GCC Secretary-General, H.E. Dr. Nayef Falah Al-Hajraf from Kuwait, was officially announced. A former Minister of Finance, he has also headed departments and portfolios dealing with economics and planning. In keeping with his expertise, the expectation is that the Secretariat will place special emphasis on economic issues.

The new Secretary-General is as different from all of his predecessors as they are different from him. He is from the Ajman tribe, which has deep roots in Bedouin culture. By all accounts he is unpretentious, professional, and effective. One high-ranking Kuwaiti official, who has held prominent positions over the course of several decades, told me today that, “He is the best Minister of Finance we have ever had.”

If the new GCC Secretary-General is to emphasize economic issues, he will almost certainly find that diversification of the GCC economies will remain a regional priority. There is no way around it. A vibrant younger population in the GCC and Arab region will require structural changes and reforms. An encouraging sign, apparent to this writer during his consecutive stays in three GCC countries at this time, is the GCC governments are already rebalancing their roles.

They are doing so both as an employer and a provider of services, and they are turning to private-public sector partnerships. Restructuring of economies through the introduction of bankruptcy laws, assistance to debt markets, and placing focus on assisting distressed companies will likely go a long way toward a strengthened GCC region. Attracting heightened foreign direct investment with streamlined registration and licensing procedures for investors, for example, could be accomplished through a united GCC.

Outgoing GCC Secretary-General Dr. Al Zayani leaves behind a formidable legacy. He has witnessed an eventful period during his time leading the Secretariat. Happening on his watch were the “Arab Spring,” the rise of the Islamic State group, civil wars in Syria and Yemen, the intra-organizational rift, as noted, and varying degrees of hypertension resultant from Iranian interference in what GCC nationals are quick to point out are quintessentially Arab affairs.

In Yemen, Dr. Al-Zayani personally led numerous efforts to bring the United Nations in to enact UN Security Council Resolution 2216, which calls for a ceasefire and for the Houthi rebels to lay down the heavy weapons that they seized when they took over the capital of Sana’a. The resolution remains the main diplomatic formula for resolving the armed conflict dimension of the situation in Yemen.

Facts and Figures for Context

As to where the GCC is headed, some facts and figures might help to add context to the role and responsibilities of the member-states at present. They also help illustrate how far the member-countries have come and what dynamics might shape their futures.

The GCC member-states account for around 30% of the world’s proved crude oil reserves and around 20% of the world’s proved natural gas reserves; the GCC’s population is approximately 50 million, half of whom are expatriates; Saudi Arabia and the UAE account for 75% of the GCC’s $1.4 trillion economy and 80% of its population; and average per capita income across the six countries is around US $27,400.

The extent to which the GCC region has diversified its partnerships over past few decades is revealing. Asia, for example, presently accounts for over 60% of the GCC countries external trade. Contrast that figure with those of 1992, when GCC-European Union (EU) trade was 24% of total GCC external trade; GCC-U.S. trade was 18% of total GCC external trade; and GCC-China trade was merely 2% of total GCC external trade. In 2018, GCC-EU trade was 11% of total GCC external trade; GCC-U.S. trade was under 6% of total GCC external trade and less than the shares of GCC trade with India and Japan; and GCC-China trade comprised 11% of total GCC external trade.

In addition, the GCC has negotiated several Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). A GCC FTA with China is close to completion. GCC-EU FTA negotiations, which began in 1987 and were as robust as any, came to an abrupt halt in late 2008. The reason: the GCC claims that the EU kept moving the goal posts in the form of intervening in the GCC countries’ domestic affairs. In marked contrast, GCC-U.S. FTA negotiations never started, though there was a Trade and Investment Framework Agreement signed in 2012.

Regional Defense Analyses

In the realm of military and strategic defense considerations, much of Western media’s reports about the GCC region’s capabilities, trends, and indications suffer from a bias of viewing the region from the outside in rather than from the inside out. Selected analyses of GCC Assistant Secretary-General for Political Affairs and Negotiations H.E. Dr. Abdel-Aziz Hamad Aluwaisheg at the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations’ 28th Annual Arab-U.S. Policymakers Conference bear this out.

In addressing the Conference, Dr. Aluwaisheg took exception to the way that foreign leaders have examined and addressed what they perceive to be the GCC region’s defense needs. Despite their coming up with some new and other refurbished proposals, what most have had in common, he said, is that they deny local agency by the countries most threatened in the Gulf. In particular, they have tended to ignore the work that has been done by the GCC countries themselves over the past several decades to establish what, in their view, is “a fairly robust collective security system.”

More pointedly, Dr. Aluwaishaig stated that, “During the past 38 years, [the GCC] has established an elaborate security architecture, which was crowned last November with the appointment of General Eid Al-Shelewi as the General Commander of the GCC Unified Military Command (GUMC). Overseen by the joint chiefs of staff of member-states, the GUMC coordinates the work of all the GCC countries’ military services, including the land, naval, air force, and air defenses of the member-states. Despite the recent intra-GCC difficulties, the joint chiefs of staff and other officers from the GCC six member-states have been meeting regularly, intensifying their efforts since May, with Iran’s escalation of aggression against international shipping in the Gulf and oil installations on land.”

In sum, from where Dr. Aluwushaig sits, which is right next to the organization’s Secretary-General, “The Gulf security architecture already exists. The foundation should be based on Saudi Arabia’s own efforts, those of its GCC allies, and the GCC well-established collective security instruments. It also allows for the participation of the GCC’s external partners, as protecting international waterways and the freedom navigation in the Gulf is a joint international responsibility.”

Looking Ahead

With those frames of reference in mind, the imminent 40th GCC Summit offers an opportunity for perspective on events of the past year. It comes at a time when Kuwait and Oman have worked very hard to try to find a compromise to the intra-GCC rift. It is conceivable that the unwarranted Iranian attacks on oil tankers and critical infrastructure, first in May and again in September, contributed to new strains of analyses within the GCC member-states. Iran’s aggression this summer sent shock waves not only through the region but around the world.

The quick response by Saudi Aramco to repair the damage and the UAE’s efforts to avoid open war through appeal to the United Nations have helped to restore a semblance of stability and order to the region. All GCC policymakers, however, will be hard pressed to disagree that in the longer term a united GCC is a more effective tool for preserving mutual defense than a divided GCC.

In this and in other regards, U.S. leadership remains important. Throughout the internal GCC dispute, the U.S. Departments of Defense, Treasury, and State have all been clear that any U.S. programs and exercises would include all members of the GCC, without exception. Today, Washington’s continuing efforts to promote joint military exercises, counter-extremism finance training, the Middle East Strategic Alliance, and a range of other programs have been designed to provide a base line for inclusive action and collective pursuits.

As this writer has observed previously, the GCC, forged amidst regional uncertainties and witness to incredible changes within its member-states since it was established, has never been free from criticism. Perhaps misunderstood or misappreciated at times, it remains an important organizational grouping whose work contributes much to the lives of its member-states citizenry and the global community at large. Founded and operating according to the principles of consultation and consensus, the occasion of the GCC’s 40th Heads of State Summit offers an opportunity to examine the past, take stock of the present, and look toward a future with a continued shared commitment by GCC member-states to security, stability, and prosperity in the Gulf.

![]()

For More Information:

- H.E. Dr. Abdullatif Bin Rashid Al Zayani – “The Road of Interdependence” (November 21, 2019)

- H.E. Dr. Abdel Aziz Hamad Aluwaisheg – “Assessing Gulf Security Architectures” (October 23, 2019)

- Dr. John Duke Anthony – “The Gulf Cooperation Council in the Rear View Mirror and the Front Windshield: Navigating the Shoals of Regional Uncertainties” (December 8, 2018)

- Dr. John Duke Anthony – “Analyzing the 38th GCC Summit: A Counter-Interpretation” (December 21, 2017)

- H.E. Dr. Abdullatif bin Rashid Al Zayani Opening Keynote Address at the Seventh Annual Gulf Research Meeting (August 31, 2016 )

- Dr. John Duke Anthony – “The Founding of the Gulf Cooperation Council: A Retrospective and Diplomatic Memoir” (December 29, 2015)

- A Discussion with Gulf Cooperation Council Secretary General H.E. Dr. Abdullatif bin Rashid Al Zayani (October 7, 2015 )

- H.E. Dr. Abdullatif bin Rashid Al Zayani – “Envisioning the GCC’s Future: Prisms for Perspective” (August 28, 2015 )

- Dr. John Duke Anthony – “The Future Significance of the Gulf Cooperation Council” (June 7, 2012)

- Dr. John Duke Anthony – “The GCC, Iran, and Iraq: Gulf States Deal with Twin Threats to Security” (January 1996) [PDF]

- Dr. John Duke Anthony – “The Gulf Co-operation Council” (Spring 1986) [PDF]

Author

-

Dr. John Duke Anthony is the Founding President and CEO of the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations. Based in Washington, D.C., the National Council was established in 1983 as a non-profit and non-governmental organization. Its mission is educational. The focus of the Council's work is broadly on Arab culture, society, economic development, foreign relations, geopolitics, geoeconomics, and regional dynamics. Its quest is to continuously strengthen and expand the positive ties between the American and Arab peoples. In June 2000, on the occasion of his first official visit to the United States, Moroccan King Muhammad VI knighted Dr. Anthony, bestowing upon him the Order of Quissam Alouite, Morocco's Highest Award for Excellence. Dr. Anthony is a Member of the U.S. Department of State's International Economic Policy Advisory Committee's Subcommittee on Sanctions; a Life Member of the Council on Foreign Relations since 1986; the only American to have been invited to attend each of the GCC Ministerial and Heads of State Summits since the GCC's establishment in 1981; and the only American to have served as an Official Election Observer in all of Yemen's Presidential and Parliamentary elections.