Download as PDF: English | عربی AR

“After 37 years, it would be a shame if all of our efforts and what we have achieved were to come to an end.”

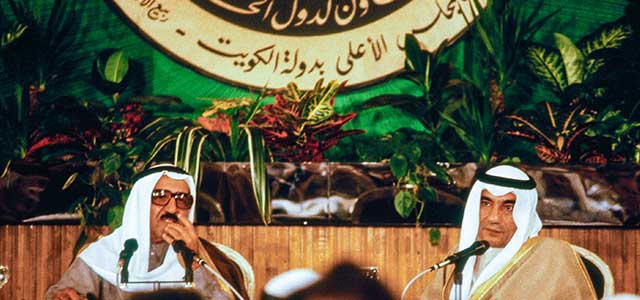

In his opening remarks to the assembled throng, Kuwait’s Amir, HH Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Sabah, spoke from his heart. He did so to a hushed gathering of his peers representing the six member-countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC): Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), at the organization’s recent 38th Ministerial and Heads of State Summit.

Had there been a more solid substance than the carpet beneath their feet, one could have heard a pin drop. The muted tones were not merely out of respect for one of the organization’s two longest-serving leaders (the other being HM Sultan Qaboos of Oman). They were also a reflection of the serious juncture at which the summiteers were gathering. For the past six months, the organization has been witness to a crisis the likes of which the six-country grouping has never before experienced between and among the members. In addition, it has also been beset with an unprecedented and extraordinary array of exceptionally difficult issues. The effort to manage and deal effectively with such issues would strain the statecraft skills of any diplomat or foreign policy decision maker.

Yet, despite the moment’s need for context, perspective, and detached analysis, perhaps no previous summit has been as misreported as this one. The phenomenon was apparent from even before it was announced that invitations for the summit had been sent.

Contexts for Context

This writer was in attendance as the GCC gathered on this occasion at the Bayan Palace in Kuwait, as he had been at the previous 37 summits dating back to May 1981. Here, though, it is important to acknowledge several things at the outset. One, is that most writers and analysts labor under limitations. To begin with, we are outsiders. No matter how diligent the effort, the endeavors of outsiders in obtaining knowledge pale in comparison to the knowledge of insiders. Such an acknowledgment must frame any effort to inform and educate others about a phenomenon as elusive of fulfillment, as comprehending accurately and adequately what did and did not transpire at a summit at which the attendee was an observer, and not a principal or participant. Certainly, that’s what this endeavor is.

Another limitation has to do with the media. In interpreting and, in some cases, challenging media reports about what did and did not happen at such an internationally high profile meeting, it is also important not to be seen as media-bashing, seeking to score points at another’s expense, or engaging in any kind of one-upmanship. For better or worse, everyone seeking to become better informed about the world in which we live is enormously indebted to the media for however much or little we know. This is true for specialists and generalists alike.

As to how and why some might fail to adequately and accurately report the reality of what occurs at a fast-paced event such as the recent summit in Kuwait, reasons abound. One need only consider the extraordinary deadlines placed upon international correspondents by their editors, media owners, and readers. These provide a sense of how difficult, and at times seemingly impossible, it can be for one to have facts in order and be able to make sense of everything before going to print.

In the case of the GCC summit in Kuwait, there were also unexpected concurrent regional developments of immense importance. One was the unexpected death of former longtime strongman president of Yemen, Ali Abdullah Saleh, which alone was distracting in the extreme. Compounding difficulties in processing and interpreting that momentous change was news of an imminent declaration by U.S. President Donald Trump recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and signaling his intention to relocate the American Embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

For anyone, it would be hard to imagine two more simultaneously rattling and intrusive phenomena as these to add to the already difficult task of discerning the meaning of the GCC Summit in Kuwait. Both were practically guaranteed to distract attention from the summit, and did.

This background is offered to help place in context facts and other facets of the summit in Kuwait that have been either overlooked or misreported.

Summit Representation

Some of the more egregiously misleading accounts of the summit had to do with the nature and level of representation in Kuwait at this year’s summit. For example, some reports made sweeping judgements regarding the fact that only two heads of state were in attendance. Overlooked, however, was that this situation is hardly without precedent. It was and is nowhere near as big of a deal as many have tended to imply. One only need reference previous years’ gatherings where fewer than half of the member-countries’ heads of state were present to realize that this was not such an extraordinary occurrence.

Some went further. They allowed their readers to infer that the lack of a full complement of members of the principals in the GCC’s Supreme Council was ominous in the extreme. Reports indicated that in there being less than one hundred percent attendance by members of the organization’s premier decision-making body, and the one comprised of the six rulers, meant that the grouping’s death knell was at hand. Nothing of the kind was or is the case.

All six countries were represented at the summit, albeit at different levels of rank. As this has happened quite a few times before, nothing beyond the fact itself need have been interpreted.

Context on Bilateral Accords

In another account, immediate analyses of a new “joint committee for cooperation and coordination” in military, political, economic, trade, and cultural fields between Saudi Arabia and the UAE lacked critical perspective.[1] Rather than sounding the GCC’s death knell, the bilateral partnership can be regarded instead as a welcomed and value-added move that can serve to strengthen the GCC.

The announcement of the more formalized partnership, made just before GCC summit proceedings opened in Kuwait, signifies the advancement of a multifaceted bilateral agreement between two of the GCC member-states that has been in the works for some time. It had to do with providing a more organized framework for the existing focus and priorities of cooperation between the two countries.

Rather than sounding the GCC’s death knell, the bilateral partnership between the UAE and Saudi Arabia can be regarded instead as a welcomed and value-added move that can serve to strengthen the GCC.

Largely lacking in the coverage of the announcement, however, was that its eventuality, purpose, and objectives were declared two years ago. At the time, virtually the entire GCC membership hailed the trending towards such a bilateral agreement between the two countries as an important and welcomed step. A near unanimous theme among the commentaries then was approbation of how such an accord would strengthen and expand the nature and extent of cooperation between and among the members in numerous fields of activity and engagement. One need only reference the final communique from the 2016 GCC Ministerial and Heads of State Summit in Bahrain lauding the burgeoning Saudi Arabian-UAE partnership to place this development in context.

Here, perspective is in order. In international organizations the world over, bilateral agreements entered into by fewer than all of the members are not only common. They abound.

Numerous bilateral accords between two or more of the member-states exist within the GCC. Like the one proclaimed just before the most recent GCC summit in Kuwait, such accords are neither unusual, surprising, nor shocking. Yet these are the attributes that the media applied to the one announced immediately prior to the most recent summit.

That the opposite was true might otherwise be excused as a lapse made in haste but for the fact that there was no reason for the omission. Nor was it without costs. Context was lacking. It may no longer be the case that many are unaware of what the GCC is. Yet, still, for the overwhelming majority, the result of the media’s reportage in this instance compounded misunderstandings.

Four examples of prior intra-GCC member-state cooperation and collaboration should suffice. One relates to Oman and Saudi Arabia. These two entered into a border agreement that reflected their consensus on the precise line of demarcation for the internationally recognized boundary between them.

Another example relates to linkage of the GCC states’ electrical grids. The project was launched with separate linkages of Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia on one hand, and Oman and the UAE on the other. This writer was present when the Amir of Kuwait flicked a switch that illuminated the border areas of four of the GCC members. The piece-by-piece connection of member-states power grids, which began with the participation of fewer than all six members, represented an immensely important intra-GCC strategic breakthrough. It has contributed over $1 billion in savings to GCC member states over the past three years and is projected to be worth even more in investments and savings in the future.[2]

A third example occurred in 2011. When violent demonstrations rocked Bahrain in the wake of the so-called “Arab Spring,” Bahrain’s government immediately asked neighboring Saudi Arabia for assistance. The Kingdom, joined by Qatar and the UAE, mobilized and deployed armed units to Bahrain. Contrary to what was widely reported at the time by the media, however, the role of the three GCC countries’ armed forces was not to fight the rebels. Rather, it was to protect Bahrain’s industrial and national security infrastructure. Doing so enabled Bahrain’s own law and order enforcement resources to engage with the demonstrators. Satellite photos verified this positioning of the intervening forces.[3]

A fourth example is when the archipelago country of Bahrain and Saudi Arabia decided to link their two countries physically. They did so by means of a causeway. This writer was present at the ceremony in November 1986 when poets from all six of the GCC countries came to orate their tributes to this bilateral accord and act. Without exception, all agreed that the move was not only welcomed but would help strengthen the GCC as a whole.

These are but four of numerous other examples where two or more GCC countries opted to institutionalize the administration of their interests that had previously been addressed less effectively or in an ad hoc fashion. In short, these kinds of partnerships are not necessarily the negative phenomena that the media and observers have sometimes implied; the truth is nearer the opposite.

The fact that some but not all members of the United Nations have opted to join the World Trade Organization, that some but not all of the members acknowledge the sovereignty of the International Criminal Court, and that Canada, Mexico, and the United States entered into the North American Free Trade Agreement hardly signaled the demise or even the weakening of the world’s most important international organization; if anything, such agreements in numerous cases helped strengthen the body.

Viewed through a different set of lenses, then, the meaning, substance, and significance of the Saudi Arabia-UAE accord announced before the summit can be seen more clearly: a welcomed and value-added move that does not serve to weaken but rather strengthens the GCC.

Further Misperceptions and Misreporting

In a similar vein, many have pointed to the summit failing to resolve the ongoing Gulf crisis as proof that the gathering was a flop. Here, too, nothing could be further from the truth and nothing could be more indicative of a false reading of what the GCC is all about.

To begin with, absolutely no one among the summiteers expected the Gulf crisis to be solved at this meeting – or even for it to be addressed. It was never in the cards for this to occur. Truly serious matters are never solved in such settings. Think about it: why should they? In keeping with age-old cultural and political traditions, together with deeply rooted customs, the last place GCC member-state disputants expect or wish to see a serious matter resolved is at a summit. In many other international organizations, it is the same. Just because the Five Permanent Members of the UN Security Council cannot yet find a way to resolve the looming crisis involving North Korea’s nuclear weapons and missile testing is no indication that the members are preparing to fold their tents and call it a day.

As GCC Assistant Secretary General for Foreign Affairs H.E. Dr. Abdel Aziz Abu Hamad Aluwaisheg noted with regard to the ongoing Gulf crisis, “Kuwait had proposed before the summit – and all agreed – that the issue should be treated separately and in isolation of the GCC integration process and its international and regional partnerships. The aim was to immunize the GCC against internal disagreements.”[4]

Consider how different much of the post-summit analysis would have read if more had been aware that none of the summiteers intended for the crisis to be solved at this gathering. Rather, in keeping with traditional practice and cultural preference, it is fully anticipated and planned that intra-GCC crises of any kind, this one being no exception, will be resolved in due course in some other way. The resolution of this crisis, like any other, will be settled in a more professional and effective manner at another time, and quite possibly also, in another place.

As to how the crisis will end, no one can say. Those who do say, or who feign to know when and how, are likely to be only peddling an agenda. Rather, the crisis is almost certain to be resolved with as little fanfare as possible and away from the limelight. Reporters and television cameras will likely not be present.

As to the operational dynamics, if one can predict anything it is that the eventual reconciliation work will be conducted through specialized sub-committees tasked with the specific goal of achieving the objective. In this regard, Kuwait and Oman, the two of them having played all-important roles in the efforts to mediate the crisis thus far, are expected to be centrally involved.

With this as background, what, some have asked, was the reason for having this particular summit at all? Consider that it might well be for reasons other than ones that outsiders and non-specialists apparently imagined or thought would be the case. Consider that it was to illustrate that the GCC is not going anywhere, that it is not going to fold, that the organization and its six-state cooperative spirit’s end is not nigh.

Watching the Clock

In a similar vein, many commentators took pains to note that this year’s summit, which lasted perhaps 70 minutes, was far briefer than any in the past. From that fact, they leapt to conclude that this alone was indicative of the GCC’s collapse.

The process that leads some to reach such a conclusion based on their stopwatch’s reading is unfortunate and misleading. It reflects outsiders’ inclinations and wishes, perhaps unwittingly and unknowingly, to impose their preferences and desired outcomes on the summiteers’ motivations, intentions, and impressions.

Time and time again, reality has shown the folly of this analytical approach. From the summiteers’ perspective, viewed in the context of the overall reason for the GCC’s existence and its purpose, the length of their meeting was of little relevance if at all relevant. What was and is far more important is what they achieved. That is, their having collectively proved the point that the GCC remains relevant to the present as well as the future, why extend the meeting? The naysayer’s line of reasoning overlooks the more significant fact that the most important matter at hand had been settled – representatives of all six of the GCC’s members had gathered together and agreed on their next meeting.

That main point having been achieved, which was what mattered most, no one can deny that those assembled were and are among the world’s busiest and most practical people. None have extra time on their hands and certainly none to waste. With their objective having been accomplished, it made sense to call it a day, to pack up and return to their home countries so as to resume tending to other important and pressing end-of-year duties that had been put on hold during their absence.

As Kuwait’s Amir Sheikh Sabah noted at the summit, “The past few months have seen several painful incidents and negative repercussions, but we believe that wisdom will prevail. Our meeting today is an indicator that we shall continue our efforts to resolve the crisis.”[5]

Kuwait’s Centrality

That the 2017 summit was held in Kuwait might well have been fortuitous given Sheikh Sabah’s high-profile attempts at mediation in the Gulf crisis. Once Kuwait took the initiative to declare that it intended to host such a meeting and commenced to invite everyone to attend, it was practically certain that the summit would be held at its usual time. Indeed, it was also a reflection of the prestige of and respect for Kuwait’s ruler that all of the member-states attended and were represented in one form or another.

In terms of pan-GCC culture and regard for the deep roots and traditions associated with the region’s history, Sheikh Sabah holds more than one distinction that sets him apart in the eyes of many in the chronicles of the peoples of Arabia and the Gulf in the contemporary era. It was not that long ago, for example, that Sheikh Sabah was not only the dean of the foreign ministers of all six of the GCC’s member-countries. For a time, he was also dean of all the world’s foreign ministers.

Kuwait, too, has a special role in the region. Specialists differ as to which GCC country was most vital in helping to bring the cooperative experiment into being in 1981. What nearly all agree, however, is that none, save Oman and possibly Saudi Arabia, worked longer or harder than Kuwait to assist in establishing the organization 37 years ago.

It was for this reason that, at the GCC’s founding meeting in Abu Dhabi in May 1981, Kuwait made a strong case that the organization’s headquarters should be situated in Kuwait. Owing to a stroke of strategic prescience – region-wide awareness that neighboring Iraq might one day invade Kuwait, which indeed happened nine years later – the founders decided otherwise. They agreed to place it in Riyadh, geographically the furthest distance from Iran and Iraq, and for Kuwait’s distinguished diplomat, H.E. Abdulla Bishara, to be its secretary-general, a position he would be elected to for four consecutive three-year terms, a record that stands to this day.

Once Kuwait took the initiative to declare that it intended to host such a meeting and commenced to invite everyone to attend, it was practically certain that the summit would be held at its usual time. Indeed, it was also a reflection of the prestige of and respect for Kuwait’s ruler that all of the member-states attended and were represented in one form or another.

To Kuwait’s further credit, consider the following. Among the world’s developing countries and emerging economies, Kuwait is regarded by many as the “mother of Sovereign Wealth Funds” – likened by some as rainy-day savings on steroids, or national state monies that governments set aside far in advance of the day, presumably well into the distant future, for use needed at that time. It was the first Arab country to provide massive charitable and humanitarian contributions on an annualized and institutionalized basis to the world’s less fortunate. In a feat unrivalled by any other country before or since, it did so beginning in 1954, seven years before it obtained its national sovereignty, political independence, and territorial integrity.

Not to be overlooked as well is that Bahrain and Kuwait are related by familial ties and the two, in turn, are related to Saudi Arabia through the broader context of more extensive tribal ties. Kuwait, moreover, provided aid to Dubai and other emirates before the recipients could fund themselves. In addition, it provided the financing that was key to Dubai’s ability to dredge its then silt-laded port, paving the way for it to become the behemoth it has long been in terms of regional trade, investment, and the establishment of joint commercial ventures.

From its renowned centuries-old acumen in maritime trade, investment, and commerce, Kuwait arguably has more experience in launching, being a member of, and leading regional and international organizations than any other GCC country save Saudi Arabia. Prominent examples of international organizations for which Kuwait was a founding member and continues to serve as headquarters are The Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development, the Arab Towns Organization, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries, and the Gulf Investment Corporation, which invests moneys on behalf of the member-organization in income-producing ventures internationally.

Marking the Calendar

In their meeting, short as it may have been, the GCC affirmed their progress on important integration matters, assessed regional crises, and planned for their next meeting. Developments were noted and continued work was encouraged on the GCC Unified Military Command,[6] intra-GCC police coordination, heightened cooperation in counter-terrorism, efforts to end money-laundering for extremist ideologies, and on economic integration measures. Included in the actions taken at the summit was the adoption of recommendations to complete the GCC Economic Union by 2025, which will build further on the declared and agreed but not yet fully functioning GCC Customs Union and the GCC Common Market.[7]

The GCC summiteers also reviewed and discussed developments in Iran, Iraq, Palestine, Syria, and Yemen. Notably, the GCC adopted a proposal to launch a strategic dialogue with Iraq, with regard to which Saudi Arabia has already commenced steps, and affirmed their commitment to participating in the reconstruction of Iraqi areas recently liberated from the so-called Islamic State.

At the summit’s close, it was announced that the next GCC summit is confirmed for 2018. While it was Oman’s turn to host and chair the summit in 2018, the Sultanate quickly utilized a mechanization formalized just last year to transfer the position of hosting, and perhaps also of chairing, next year’s annual summit to Saudi Arabia. A benefit in this is that Riyadh is where the GCC Secretariat is headquartered. Oman will remain as chair of the ministerial and sub-committee meetings of the GCC despite relinquishing the role of hosting 2018’s annual summit.

Thus, importantly, the situation is one where the member states are far from folding their tents and calling it a day. Rather, they assented to there definitely being a next meeting of the GCC’s Supreme Council and they also agreed on the venue. The member-states’ representatives proved that the organization continues to matter, and that they are by no means inclined, let alone planning or prepared, to jettison the GCC experiment.

Organizational Dexterity

In light of this year’s summit, and what was and was not accomplished in Kuwait, it would seem that the question of whether the GCC has or no longer has any relevance misses the point. Rather, more appropriate and enlightening analyses would encompass finding appropriate set of lenses through which to view the GCC in light of its as-yet unresolved six-month crisis and as-yet not-fully-developed potential.

Should it be viewed in terms of power politics and the necessity of building, strengthening, and expanding a sub-regional coalition capable of deterring, and if need be defeating, a powerful adversary possibly bent on inflicting harm on one or more members of the sextet? Here, there is a reminder. It is the 1990-1991 Kuwait crisis, when neighboring Iraq invaded and occupied Kuwait for six months and virtually every one of the GCC’s members rallied to Kuwait’s assistance.

Or, should the GCC be seen from the vantage point of a different kind of coalition? Might the organization remain comprised as a body of representatives of the same six countries committed mainly to varying degrees of economic, social, and administrative functionalism – addressing specific among the pan-GCC challenge to continuously strive to enhance the material and social well-being of the member-states’ citizens?

The answer, importantly, is reflected in the hundreds of meetings the GCC has had since its inception other than its annual ministerial and heads of state summits and the quarterly meetings of the ministerial council, which is comprised of the six countries’ foreign ministers. Viewed in this context, it will be seen that this is exactly what the organization has mainly been from Day One. Indeed, the content and membership-wide focus of the organization has been overwhelmingly wedded to the values, principles, and practice of functionalism in its overall approach to regional challenges, opportunities, and issues. In a sense, this makes for the GCC Secretariat being arguably the GCC region’s single most effective “think tank” or public policy research institute.

The content and membership-wide focus of the organization has been overwhelmingly wedded to the values, principles, and practice of functionalism in its overall approach to regional challenges, opportunities, and issues.

One might ask, how could this be if one hasn’t read about it? Here, again, is evidence that most of the GCC’s foreign observers, in viewing the organization from the outside and not from the inside, are simply unaware that literally hundreds of function-focused meetings take place on a regular basis year-round. This result is understandable, and likely stems from the fact that most Western outsiders, and especially ones in the United States, do not speak, write, read, or understand Arabic, the milieu and means in which news of such meetings along functional lines occur.

In viewing these two organizational approaches, namely the pursuit of meaning, relevance, and effectiveness in the councils of national and international power and influence, on one hand, and, on the other, working within a functionalist frame of reference, consider that the GCC is engaged in the pursuit of both objectives. Indeed, to differing degrees at different times, this organizational dexterity is what the GCC has deftly deployed over more than three decades.

The Work of the GCC

The question of whether the GCC retains any meaningful relevance overlooks an important factor. It fails to consider the powerful propellant force that was the earliest stimulant inspiring economists and other specialists in the social sciences, together with various technocrats and bureaucrats in the six countries, to coalesce institutionally. The record reveals that the functionalist approach, albeit operating away from the limelight, is the older of relevancy’s two configurations and orientations. It is also the dimension of the GCC’s headquarters with the most numerous departments and staff.

Consider, for example, the composition of the GCC’s personnel. Until the last few years, the number remained fairly constant in the hundreds of employees. This in itself, however, conveys less of interest and value than the nature and extent of these GCC employees’ workaday routines and the tasks they are expected to register progress towards achieving.

These personnel operate within the GCC Secretariat-General’s relevant and respective departments, committees, and subcommittees, each of which is represented by personnel from all six GCC countries. Together, not separately, they go about addressing common challenges defined by the kinds of economic, educational, social, cultural, environmental, and human resource development functions they administer.

Understanding this aspect of the GCC’s work would be difficult for most outsiders lacking, as most do, access to the organization’s headquarters. But for those that have or have had access, there is no question that the overwhelming body of GCC personnel have next to nothing to do with considerations related to power politics, geopolitical coalition-building, and/or the purchasing of state of the art weaponry. Nor are they focused on a summit like the GCC, broader Arab, and still broader Islamic world one that President Trump held this past May in Riyadh, or the two summits with which then-President Barack Obama was involved in 2015 and 2016.

Take, for example, but one GCC division which focuses on economic issues. Examination will reveal their work is focused on areas related to the advancement of trade, to heightened intra-regional investment, and to the movement of capital, goods, services, and labor between and among the member-states.

The overwhelming body of GCC personnel have next to nothing to do with considerations related to power politics, geopolitical coalition-building, and/or the purchasing of state of the art weaponry.

The focus on any given day for others will more likely be on harmonizing the math and science components of the six state’s educational curricula, the better to prepare the GCC citizenry for more effective technical and technological advances. Or the focus may be on patent protection and narrowing the differences in weights, measures, and other standards applicable to their economic cooperation. Or the focus may be on all of these things and half a dozen more.

As Dr. Abdulkhaleq Abdulla noted at the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations’ 23rd Arab-U.S. Policymakers Conference in 2014, “Gulf integration works through 46 different ministerial councils, (and) some 370 different technical committees that work 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year.” This amounts to over seven hundred different meetings every single year involving over ten thousand Gulf officials.[8]

Any effort to describe and analyze this feature of the GCC from as detached, clinical, and objective a perspective as possible will reveal new avenues for assessing the organization. They bring forward a set of pan-GCC visionaries who function as change agents engaged in building a more robust, cohesive, and effective bloc of like-minded countries and peoples capable of furthering the modernization and development of their societies.

In sum, by far the greater number of GCC employees work on endeavoring to improve the quality of life for the six member-countries’ citizens. If that is not a criterion for a sub-regional organization’s relevance, it would be hard to know what is.

Foundational Dynamics and Geo-Political Realities

In assessing what the GCC is and isn’t, where it has been and where it may be going, it can be helpful to remember some of the dynamics foundational to this regional grouping. No other six contiguous and natural resource-rich political entities anywhere can match, let alone surpass, the GCC member states. In terms of their innate power, control, and influence regionally and in the global arena, they have no peer. Geographically, they lie adjacent to what are arguably the world’s most important sea lanes.

The GCC’s northernmost point at one end embraces all of Kuwait, situated next to strife-torn Iraq. At the other end is the Sultanate of Oman, which lies next to civil war-wracked Yemen. Spanning the space in between landward and seaward is the entire east Arabian littoral, inclusive of what many regard as planet earth’s most strategically vital waterway: the Hormuz Strait, through which 18 million barrels of petroleum and massive amounts of liquefied natural gas flow each day.

Emotions may be high in the present, but the GCC as an organization remains in being. Its 38th Ministerial and Heads of State Summit proceeded like all the others before it of years past. It was complete with a post summit briefing for this writer and other attendees by the organization’s secretary general, H.E. Dr. Abdul Latif Bin Rashid Al-Zayani, together with Kuwait’s Foreign Minister and the Ministerial Council Summit’s Chair, H.E. Sheikh Sabah Al-Khaled Al-Hamad Al-Sabah, as is and has been the custom at all GCC summits since the organization’s inception in 1981.

As to whether the GCC will retain its relevance in the future, where others have expressed their doubts, this writer has no doubt that it will. The case of “necessity being the mother of invention” has been noted. In this context alone, there would appear to be no doubt that the need for such a sub-regional organization, which could hardly be more apparent than at the present, will likely continue to be the case. One need only cite Iran, Iraq, and Yemen, to name but three reasons. The need for the member-countries to consult and do so regularly with regard to any one of the three is more than sufficient to underscore the necessity.

The importance of deep-rooted traditions, and the custom of consultation and consensus, remains the same today as was the case in 1981, when the GCC was founded.

![]()

[1] News of announcement at “President issues Resolution forming UAE-Saudi Joint Cooperation Committee,” WAM – The Emirates News Agency, 4 December 2017. http://wam.ae/en/details/1395302651870

[2] Figures from GCC Interconnection Authority bulletin cited in “GCC power grid connectivity seen generating $33bn over 25-yr period,” Gulf Times, 21 May 2017. http://www.gulf-times.com/story/549605/GCC-power-grid-connectivity-seen-generating-33bn-o

[3] See Dr. John Duke Anthony’s “The Intervention in Bahrain Through the Lenses of Its Supporters,” Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research, June 30, 2011. https://ncusar.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/2011-06-30-Intervention-in-Bahrain.pdf

[4] See H.E. Abdel Aziz Aluwaisheg’s “GCC agrees further integration at annual summit,” Arab News, 18 December 2017. http://www.arabnews.com/node/1210641

[5] Quote from “Kuwaiti emir calls for change in GCC structure,” Associated Press, 6 December 2017. https://www.elliotlaketoday.com/world-news/two-day-gulf-summit-ends-within-hours-amid-qatar-crisis-783100

[6] For background on the GCC Unified Military Command, see Dr. John Duke Anthony’s “Gulf Cooperation Council Establishes Unprecedented Joint Military Command,” National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations’ Arabia, the Gulf, and the GCC Blog, December 11, 2014. https://ncusar.org/blog/2014/12/gcc-joint-military-command/

[7] See H.E. Abdel Aziz Aluwaisheg’s “GCC agrees further integration at annual summit,” Arab News, 18 December 2017. http://www.arabnews.com/node/1210641

[8] Quote taken from transcript of session on “Gulf Cooperation Council: Role In Regional Dynamics” at the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations 23rd Arab-U.S. Policymakers Conference, October 28, 2014. https://ncusar.org/programs/14-transcripts/2014-10-28-gcc-regional-role.pdf

![]()

Further from Dr. John Duke Anthony:

- The 1990-1991 Kuwait Crisis Remembered: Profiles in Statesmanship (August 2, 2017)

- The Founding of the Gulf Cooperation Council: A Retrospective and Diplomatic Memoir (December 29, 2015)

- Gulf Cooperation Council Establishes Unprecedented Joint Military Command (December 11, 2014)

- The Future Significance of the Gulf Cooperation Council (June 7, 2012)

- Report from the Gulf Cooperation Council’s Ministerial and Heads of State Summit in Kuwait, December 2009: What Did and Did Not Happen and What Next? (December 22, 2009)

- GCC Heads of State Summits: Context and Perspective (January 10, 2004) [PDF]

- In The Shadow Of The Clouds: Assessing The GCC’s 23rd Summit (December 26, 2002) [PDF]

- The 18th Annual GCC Heads Of State Summit: Consultation and Consensus in Kuwait (December 1997) [PDF]

- The GCC, Iran, and Iraq: Gulf States Deal with Twin Threats to Security (January 1996) [PDF]

- The Dynamics of GCC Summitry Since the Kuwait Crisis (July 1992) [PDF]

Author

-

Dr. John Duke Anthony is the Founding President and CEO of the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations. Based in Washington, D.C., the National Council was established in 1983 as a non-profit and non-governmental organization. Its mission is educational. The focus of the Council's work is broadly on Arab culture, society, economic development, foreign relations, geopolitics, geoeconomics, and regional dynamics. Its quest is to continuously strengthen and expand the positive ties between the American and Arab peoples. In June 2000, on the occasion of his first official visit to the United States, Moroccan King Muhammad VI knighted Dr. Anthony, bestowing upon him the Order of Quissam Alouite, Morocco's Highest Award for Excellence. Dr. Anthony is a Member of the U.S. Department of State's International Economic Policy Advisory Committee's Subcommittee on Sanctions; a Life Member of the Council on Foreign Relations since 1986; the only American to have been invited to attend each of the GCC Ministerial and Heads of State Summits since the GCC's establishment in 1981; and the only American to have served as an Official Election Observer in all of Yemen's Presidential and Parliamentary elections.