An unprecedented and extraordinary event is about to occur: a heads of state summit. These, by any standard, can be and often are extraordinary events. That’s what this one is. It is so because it gathers in the capital of the United States President Barack Obama with the representatives of the six Gulf Cooperation Council countries: Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. The two-day summit is set for May 13-14, 2015.

GCC leaders are scheduled to meet with the president in Washington on day one and on day two gather with him in the more capacious and secluded confines of Camp David. The latter venue is a longtime private presidential meeting place in the Maryland foothills, which is conducive to wide-ranging and deeply probing discussions on matters of common, timely, and varying degrees of urgent interest to the president, his advisers, his guests, and their advisers. The focus of this essay is the issues, challenges, and opportunities that will focus the principals’ attention while there.

The Summit’s Participants in Context

That the summit is occurring at this time is no mere coincidence. In terms of the GCC-U.S. relationship, it brings to the forefront the chief representative of the world’s most militarily, economically, and technologically advanced nation. Joining him will be the leaders of six neighboring Arab Gulf countries from what is arguably the world’s most strategically vital region that are little known and even less well understood by the American people as a whole.

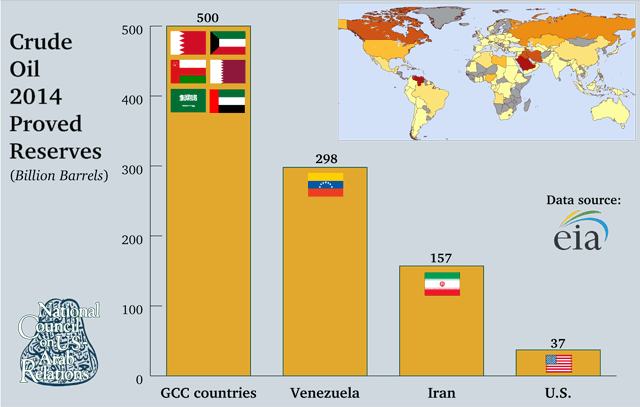

What needs to be better comprehended by the American public regarding these countries are the roots and nature of their multifaceted strategic importance not just to their peoples and immediate region, but also the United States and the world in general. To begin with, the six GCC countries possess thirty per cent of the planet’s proven reserves of oil, the vital strategic commodity that drives the world’s economies. Collectively, they are also the holders of the developing world’s largest reservoir of financial assets, as measured in the trillions of dollars.

In addition, the GCC countries have no rivals in their combined positive impact on the American aerospace and defense industries. In the past half-decade, their purchases of U.S.-manufactured defense and security structures, systems, technology, weaponry, ammunition, training, maintenance, and operational assistance have massively impacted and continue to impact the American economy.

[pullquote]The dynamism and mutuality of benefits in the U.S.-GCC relationship are envied by virtually every country that wishes it could accomplish anything remotely similar.[/pullquote]The purchases of American export goods and services by these countries have provided jobs essential to the material wellbeing of millions of Americans. They have extended production lines of products that would otherwise no longer be available. As a consequence, they have lowered the cost per unit of many American manufactured goods. In so doing, they have thereby enhanced the competitiveness of this component of the American economy to a degree envied by virtually every government or corporation in other countries that would wish they could accomplish anything remotely similar.

Even so, underlying all of these U.S.-GCC country-derived assets, strategic advantages, and economic gains is an abiding concern. It is not just an American concern. It is a much larger international concern. It is that the GCC countries – together with key features of the existing regional order – are threatened to a greater extent than at any time in the modern history of their relationship with the United States. As to which of the challenges enumerated herein is a greater threat than another varies from one viewer to the next.

To the GCC Countries’ East

Running through most if not all of the threats as perceived by the GCC countries is unquestionably their concerns regarding the policies, positions, actions, and attitudes of the government of a single country: Iran. The summit is thus what many in the GCC region – given the view that the American media has largely missed or chosen to ignore the point – would regard as commensurate with a teachable moment for reasons over and beyond whether an agreement will be reached with Iran regarding its nuclear program.

To be sure, the issue of Iran’s nuclear project is of major, and to some, of paramount importance. However, the larger and more pervasive issue as far as most of the GCC countries are concerned has been and remains Iran’s interference in their internal affairs. The accusation, as one might expect, is one that Iran denies but for which the evidence is at once massive, multifaceted, and irrefutable.

Undoubtedly one of the most pressing, difficult, and challenging tasks for the American side will be to lay to rest suspicions by some on the GCC side that the United States, despite all its words to the contrary, is in fact laying the groundwork for a fundamentally different relationship with Iran in the remaining days of the Obama administration. Here is where the White House will want to find still more effective ways to reassure its GCC interlocutors that such a deal as is scheduled to be completed by the end of next month will not threaten GCC countries and that any deal that the P5+1 – representing the Five Permanent Members of the United Nations Security Council, i.e., China, France, Great Britain, Russia, and the United States, plus Germany – may reach with Tehran is not meant to strike – nor need it entail – a new strategic relationship with Iran at their expense.

How that might be effectively and credibly achieved is difficult. Is it, as some have suggested, necessary that the United States offer a guarantee to come to the defense of any of the GCC countries in the event of an Iranian attack, threat, or intimidation? Whatever the merits that such a possibility might have theoretically – which is not entirely new, as this writer knows of at least one GCC country cabinet minister who as far back as the 1970s wanted then U.S. Secretary of State and National Security Council Adviser Henry Kissinger to extend serious and favorable consideration to such a proposal, which ended up going nowhere – it is highly doubtful President Obama or even his successor could marshal sufficient American popular support behind such a proposal to enable it to pass the Congress.

Even the surfacing of such an idea that in other times might seem outlandish is in and of itself a sign of the times. Add to this widespread distrust of how credible the United States is when it says it is not pivoting to Asia. There remains among some disbelief that America is not re-balancing its global strategic posture and interests.

Many in the GCC countries, too, speak of the United States showing signs of mission fatigue in conjunction with its longstanding, costly, and high-profile presence in Arabia and the Gulf. Others muse that an unexpected incident at sea, in which perhaps an American naval vessel is attacked, sabotaged, or in some way crippled in an act of deliberate malfeasance, is waiting to happen with possible plausible deniability by the perpetrator.

To the GCC Countries’ South

Adding to the moment, the summit comes on the heels of a ceasefire following the unprecedented Saudi Arabian-led assertiveness with regard to Yemen. To prevent the unrest there from spreading to the kingdom, Riyadh succeeded in forging a coalition of thirteen other countries, including even relatively otherwise isolated Sudan, to mobilize, deploy forces, and/or provide important logistical and operational support as well as access to facilities and air space.

At this point, the stated goal of preventing the Houthi Shia armed rebellion against the legitimate government of Yemeni President Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi from destabilizing Saudi Arabia or threatening the kingdom’s borders has succeeded. The prospects for achieving two other objectives, however, remain uncertain. One of the goals, the effort to reinstate the ousted Yemeni President, is at a standstill.

The rebels refuse to engage in peace talks that, in their view, fail to guarantee that the alleged root causes behind their rebellion will be addressed, let alone accommodated. Their demands include greater governmental representation, a larger share of benefits proportionate to their numbers and territory in the remote northernmost reaches of the country, and a degree of autonomy that may allow them to reestablish a Shia Imamate along the lines of that which ruled Yemen for centuries prior to being overthrown in 1962.

Short of what Saudi Arabia and its allies can do to help restore Yemen’s legitimacy, security, and governmental stability, it is an open question as to when the rebellion will end. On the answer to that challenge turn the matters of when and how the proclaimed next stage of the Saudi Arabian-led coalition’s objectives can be achieved. Currently, the stated goal is to implement a widespread humanitarian relief campaign to end, alleviate, and/or manage more effectively care for the suffering of the hundreds of thousands of Yemenis who have fled their homes in fear and the more than 2,500 who have been killed and wounded.

Yemen’s Unraveling?

To be sure, President Obama is aware that the challenges Yemen represents are hardly confined to the ones cited. Indeed, as portentous to the state’s cohesion as the ones the media have emphasized are others that are at once more numerous and complex. They include secessionist movements in the south and in the Hadramawt, further to the southeastern reaches of the country; the latter is now also home to extremist jihadis. Although far less known and understood than those associated with the Houthi Shiite insurgent movement that originated in the region adjacent to Saudi Arabia in the country’s northwest, these are every bit as dangerous if not more so.

What is more, these additional challenges are arguably laced with even farther-reaching implications for Yemen’s, the immediate region’s, America’s, and other countries’ national security, defense, and related interests than the Houthi rebellion represents. Indeed, it is in conjunction with the reality of such multifaceted threats to a country’s security and stability that one confronts the adage that “Capital is a Coward.” The United States is specifically aware that foreign investment as a vehicle for helping to alleviate Yemeni poverty and deprivation will not arrive if it and the countries of the region fail to act quickly to arrest the state of chaos that has gripped the country.

Moreover, in any strife-torn nation, which – in common with contemporary Iraq, Libya, and Syria – is what Yemen has become, instability and the absence of legitimate authority can make even the hardiest of humanitarian commitments come to a standstill. They can be why would-be benefactors and aid providers adopt a wait-and-see attitude and, understandably, explain why extraordinary caution all too often becomes the watchword before such international caretakers do their work, which is to intervene to save lives, distribute food and medicine, and provide shelter for refugees and the internally displaced. This, too, is what has occurred in and is continuing to happen to Yemen, making the situation there so precarious and difficult as to preclude any ability to foresee or predict the eventual outcome.

Affirming U.S.-GCC Cooperation

Much has been speculated about how this summit is vital for the future relationship between the United States and the GCC countries as a continuation, although more purposeful on the part of the GCC, of a strategic partnership. With regard to Yemen, the partnership can be seen in U.S. moves in support of the Saudi Arabian-led Operation Decisive Storm, U.S. support with regard to successful passage of UN Security Council Resolution 2216, intelligence sharing, naval maneuvers off Yemen’s coast, and American tracking of Iranian ships bound for the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea as a possible optical show of the Islamic Republic’s “force” in support of the Houthi rebels.

Additional recent examples of the U.S.-GCC strategic partnership can be seen in: ongoing extraordinary U.S. commitments to providing still greater consignments of arms and ammunition as well as training, educational exchanges, and political-military support over the past two months, inclusive of a steady stream of high-level leadership exchanges. In this regard it is notable that the kingdom’s new and relatively untested Minister of Defense, who is the king’s son and new Deputy Crown Prince, is to be among the Saudi Arabian delegation led by Crown Prince and Minister of Interior Mohammed bin Naif.

Still further examples would include the actual onset of training announced over a year ago for an American, Saudi Arabian, and other countries’ agreed force of better equipped and prepared Syrian rebels. This force is designed to take the fight to ISIS and/or the Assad regime in Damascus in a more systematic and coordinated manner, although the extent to which the Obama Administration now wants the forces to oust the Assad regime has in some quarters come into question and, if so, may have become a point of contention in the U.S.-GCC relationship.

This joint effort is done with a view to having the nature and level of strategic and even tactical cooperation between the two sides as indication of more effective U.S.-GCC country strategic coordination, thereby heightening the pressure on Iran from within the region. Such cooperation is valuable if only to convey a sense of greater and more effective strategic oneness in not allowing Tehran to make further regional inroads at Arab expense in countries beyond the ones it has already undeniably made in Iraq, Lebanon, Syria itself, and Yemen, albeit in the latter case to a far lesser degree than the media and other circles of influence have made the situation out to be.

Bearing Greater Importance than the Summit

As for the summit’s atmospherics going in, it is salutary that Operation Decisive Storm is over and Operation Restore Hope has begun. These new realities on the ground are likely to influence how the strategic U.S.-GCC relationship develops in the period ahead. As to its appearance, it is tempting to expect to see more of the same in terms of what has been or seems to be working to the national security and related interests of the two sides.

This is not just to indicate that one expects still additional arms sales, training agreements, and the transfer of previously sensitive technologies, although the Obama administration and its supporters are ever mindful not to appear as upsetting the overall regional military balance that remains heavily tilted in favor of Israel against the combined military might of all 22 Arab countries.

Rather, if the nuclear agreement proceeds to the rear view mirror after all these years of wrangling on all sides, of greater importance is likely to be the extent to which the nature and degree of Arab-Iranian cooperation in matters of common interest may occur and, if so, evolve in ways that benefit both sides. In that possibility, what may well be likely is a lessened American position and role in mediation and a greater reliance upon the GCC countries themselves, on one hand, and Iran, on the other, to work out whatever mutually acceptable understandings and agreements they may wish to conclude.

To the extent something like that could occur, there is every indication that many in the Obama administration would count that as a resounding success, one beneficial to the American taxpayer, to global financial markets, and to America’s and the GCC countries’ allies in Europe and Asia as well as elsewhere.

Yet only when the GCC countries are satisfied that Iran will pull back from its undeniably long and extensive intrusion in their domestic affairs and in the affairs of Arab countries farther afield is it likely for such a prognosis to come to pass. There would thus then be little doubt that there would be greater pan-GCC and Iranian grounds for heightened confidence in improved prospects for future security, stability, and the potential for regional prosperity.

Whether such a roseate picture of the over-the-horizon future has any bearing in reality will doubtlessly not turn on what may transpire at the White House and Camp David. Rather, from the Arab side, it will turn on a cessation of the kinds of Iranian international behavior that has been, and continues to be, undertaken – even as this summit convenes – at GCC and broader Arab expense.

From a possible Iranian perspective, it is difficult to see the extent to which such a scenario is likely to unfold in the immediate future. A reason is that there are too many Iranian vested interests in the perpetuation of the status quo if not also, at least in some quarters, an eagerness to continue racking up perceived geopolitical victories and breakthroughs in Arab milieus. Only to the extent that such a perceived momentum and the putative benefits that accrue to Iran’s legitimate quest for a regional position and role befitting its culture, history, and national assets and attributes take a turn towards another, far less controversial direction is there likely to be any credence to such a scenario.

The Glue: “Who are these Americans?”

Beyond the multifaceted challenges of the day, the case can be made on purely objective grounds that such a show of geopolitical force as will be represented at the summit in Washington and at Camp David can best be viewed as an “additive” – something new and more than before in the nature and extent of the American commitment to an ever stronger and healthier strategic relationship and even partnership with the GCC countries than existed before.

Indeed, it is perhaps a stretch to harken back to February 14, 1945, when then American President Franklin Delano Roosevelt met aboard the USS Quincy in the Great Bitter Lake of the Suez Canal of Egypt to exchange greetings and cement what by then was already a growing American-Saudi Arabian embrace. That meeting, the dynamics of which have been the source of much storytelling ever since, has also been made out to be the cornerstone, so to speak, of the “specialness” in the U.S.-Saudi Arabian relationship.

In truth, though, the relationship had grown special long before that. Little known to most analysts and observers, and even poorly known by most American specialists and scholars who have never lived in the kingdom or visited it for any length of time, is how American doctors based in Bahrain as part of the Arabian Mission of the Dutch Reformed Church of America used to come to the kingdom by dhows – traditional Arabian sailing boats crafted by hand – from 1917 onwards. What these intrepid pioneers in the eastern Arab world-United States relationship did was treat the sick for a week at a time while asking nothing in return.

It is the life and legacy of the early American pioneers in the U.S. relationship with Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and other principalities along the eastern coast of Arabia and the western coast of the Gulf that left such an indelible stamp upon the American-Arab relationship in the latter’s eastern-most climes that has carried down to the present day.

This little known and oft-forgotten chapter of the now generations-long special relationship between our two peoples led indirectly if not directly to Saudi Arabia’s modern day founder King Abdulaziz bin Abdulrahman Al Sa’ud to reportedly ask, “Who are these Americans?” It was in the answering of that question – in ways that revealed Americans, with their work ethos, can-do attitude, and absence of the kinds of imperial designs then associated with other Great Power interests in the region – that contributed mightily to the Saudi Arabian head of state granting a petroleum exploration concession to Standard Oil of California – today’s Chevron – and the United States.

That is the last century’s grand bargain in so far as the American, Saudi Arabian, GCC countries, and broader Arab and Islamic world is concerned that continues to this day. It is not anchored in inanimate phenomena – a physical substance, namely energy, for another greater power’s military might – and its defining chapter took place prior to air conditioning and oil. The glue that binds the two together has been and remains people. Hence, for such a summit to be held at this time is a reminder; it is not a cementer.

A New Mission for the GCC?

Even if the upcoming summit ends on an inconclusive note, the reality is likely to be anything but that. It will indicate that the region comprising the GCC is no longer likely ever again to be dismissed as it has been in the past.

Indeed, as has been evidenced time and again since the onset of the so-called Arab Spring in late 2010 and continuing through in varying dimensions and dynamics to the present, the GCC countries, if only in some instances by default, have not so much carved out for themselves a niche for trans-regional leadership. On the contrary, they have not.

Rather, it has been more a matter of realizing and acting upon the implications of knowing that Egypt, Iraq, and Syria, among the main disabled Arab polities, have taken a back seat to the stable, secure, and more economically and financially endowed, albeit smaller, Arab political entities of the Gulf to take up the slack of power and influence that the other countries used to wield.

That this has come to pass with an important American-GCC dynamic front and center of the unfolding forces at work cannot be viewed as something of ominous portents and implications for the needs, concerns, interests, and key foreign policy objectives of the countries concerned.

To try to cast the crystal ball further to the future is at this juncture neither necessary nor realistic. It is enough to state and underscore the obvious: that the GCC does indeed have a new mission within the broader Arab political sphere, that it is far more ready and indeed has been in preparation to play this role for longer than many were aware, and that its six countries bring much to the table in matters pertaining to Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, Yemen, Iran, the United States, and the world beyond. The end result is the GCC likely being at once stronger and with greater opportunities as well as challenged to a greater extent than ever before. If this summit does not underscore this new, dynamic, and reciprocally rewarding reality, few other public affairs events are likely to do so.

****************************

Dr. John Duke Anthony is the Founding President & CEO of the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations.