U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry is once again in Switzerland. He is there with his British, Chinese, French, German, and Russian counterparts with the continuing diplomatic assistance from the low-profile but effective good offices of the Sultanate of Oman. Their mission: to continue negotiations regarding Iran’s nuclear program.

Whether the negotiators will succeed remains to be seen. To be sure, a mutually acceptable agreement with Iran by six among the world’s most powerful and influential nations, on one hand, and the Islamic Republic of Iran, on the other, is no small matter. In substance as well as in procedure and desired outcome, the goals – ensuring that Iran does not produce a nuclear bomb and, to that end, agreeing on as intrusive a nature and range of inspections as any in history – are laudable. To many the world over they are in numerous ways also timely, urgent, and necessary.

Rising Arab-Iranian Tensions

Of course, not all agree. Some prominent Arabs, such as Saudi Arabia’s Prince Turki Al Faisal, view these matters differently. For example, he has repeatedly stressed that any and all talks regarding nuclear matters should be aimed instead toward producing a regional nuclear free zone. He has proposed such an internationally administered zone encompassing, “not just Saudi Arabia or Iran but the whole area, from Iran all the way across to the Atlantic, including the Arab countries and maybe Turkey as well.”

Despite such divergences of perception among regional and other leaders, the negotiators are proceeding along the lines they have been following for the past several years in trying to reach an agreement with Iran. In so doing, they are keenly aware of a rise in regional tensions. Indeed, simultaneous to the ongoing talks has been the destabilizing influence of Iran’s interference in the domestic affairs of Arab countries, e.g., not just members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), a six-state grouping comprised of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, but also Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen.

In this regard, they are especially cognizant of the GCC’s resentment that the issue of Iran’s ongoing occupation of three UAE islands and its continuing intrusions elsewhere in Arabia and the Gulf – destabilizing interventions as yet unreciprocated – was not allowed to be part of the talks. The negotiators acknowledge these leaders’ irritation at the reasons for the omission of such issues from the discussions: namely, that Tehran was opposed to the idea. In the negotiators’ eagerness to pursue an agreement of some kind – however partial and limited in its scope and potential impact – it is clear in retrospect that they were inadequately empathetic to the legitimate concerns of neighboring countries and too quick to accommodate Iran’s objections.

Even so, the negotiators argue in their defense that their efforts should not be defeated in advance – certainly not by anyone with a sincere interest in advancing the legitimate goals of regional and global peace, security, stability, and the possible accompanying prospects for prosperity.

Opponents Outside of the Arab World

Juxtaposed to the motivations and desires of an accord’s proponents are the controversial and ultimate agendas and intentions of those opposed to a potentially acceptable agreement: a group largely comprised of American neoconservatives, their Israeli allies, and other likeminded individuals. These groups have loudly proclaimed that they would have the P5+1 negotiators – representing the Five Permanent Members of the United Nations Security Council, i.e., China, France, Great Britain, Russia, and the United States, plus Germany – avoid reaching an agreement that may contain provisions not to their liking, which they believe may be imminently near to being concluded.

Make no mistake, these groups seek a profoundly different outcome. They would prefer to see America confront Iran.

The Old Iraq Syndrome

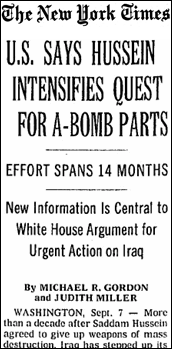

Those driving the issue in this antagonistic and provocative direction are hardly new to the American and Israeli political scenes. One need only reference, as this author did in an address to The Voltaire Institute in Brussels in 2005, their earlier influence and collective political and media clout. They effectively moved the Washington decision making process from the idea, first, of confronting Iraq militarily as a concept, then as a policy recommendation, and ultimately to the actual American-led invasion and occupation.

What these groups seek this time around, like what they sought before, has been deliberately and heavily obscured. It remains veiled in fear, myth, rumor, innuendo, and warmongering. What they have in mind bears a strong resemblance to the bill of goods sold to the American people in support of the U.S. effort to topple the regime of Saddam Hussein.

The damage they wrought in Iraq, despite its not having attacked the United States or posed any credible threat to American interests, has yet to run its course. Already, with no end in sight, the consequences are certain to cost more than a trillion dollars. Already, the human price is inestimable. Already, in addition to the thousands of Americans killed and tens of thousands wounded, are the hundreds of thousands of Iraqis killed, rendered homeless, made refugees, and maimed for life.

Even with the cessation of America’s Iraq military operations in 2011, the suicide rate of U.S. soldiers returning from the cauldron forged by the American neoconservatives, elements among their Israeli allies, and others in a post-September 11, 2001 revenge mode against Arabs and Muslims continues at a disturbing rate. Beginning in 2004, the year after the war commenced, the rate of U.S. veterans committing suicide climbed to record highs.

And many ask, “All for what?” The result toppled the Iraqi regime. It decimated the government’s security and defense forces. It sowed many of the seeds that made it possible for the Islamic State group to emerge, spread, and wreak the havoc it has wrought. It paved the way for Iran to become the country’s single largest and most influential foreign factor – without having to fire a single shot or shed a drop of blood. It allowed Israelis and Israeli agents to enter northern Iraq to assist in the training of Kurdish security forces. It advanced decades-old Israeli-Kurdish collaboration and ensured their joint goal of weakening the government in Baghdad. In so doing, it practically guaranteed that Iraq would have far fewer means and a lessened ability to threaten Israel at anytime in the foreseeable future.

Unspoken Goals

The dominant U.S. role in launching the war and in administering the occupation also succeeded in placing American advisers in Iraq’s most important government ministries. Such positioning enhanced their proximity to Iraqis authorized to plan and administer the successor government’s multi-billion dollar contracts. The result ensured that Americans would have privileged access to invaluable intelligence ahead of others. And it practically guaranteed U.S. companies a preferential position not only vis-à-vis restructuring, training, equipping, mentoring, and maintaining Iraq’s new military forces, and a favored position regarding information about the country’s energy and other economic resources. It also enabled American firms to be in a better position than might otherwise have been the case to bid on the country’s lucrative aviation, engineering, infrastructure, reconstruction, and construction projects.

As with Iraq, the goals of the American neoconservative and Israeli opponents to any accord with Iran are as devious as they are damaging. By no stretch of the imagination are they in accord with America’s and Israel’s legitimate interests. Instead, what they diligently seek might be seen strategically as a single issue and interest: serving the perceived needs of Israel and the United States under the guise of doing what is best for America and Israel when nothing could be further from the truth.

As sure as actions have consequences, these U.S. and Israeli groups would abide a forceful American-Iranian confrontation with the undeniable potential for yet another costly war. Indeed, an article titled “Time to Attack Iran,” appearing in the January/February 2012 issue of Foreign Affairs – the most widely read journal among American policymakers, U.S. policy analysts, and foreign affairs practitioners – implied just that. It suggested that, as the prospects are considerable that the United States will have to use armed force against Iran’s nuclear program eventually, it might as well proceed to do so now, when the costs would likely be less than later.

The U.S. Secretary of State’s and his negotiator counterparts’ sincere efforts to do what is arguably in American and global interests notwithstanding, many among the American and Israeli neoconservatives and other self-centric interest groups wish them to fail. To be sure, the true interests of the lead pressure groups seeking to trip them up are hardly unknown to many specialists. The danger lies in the fact that important segments of a more generalized public are largely unaware.

Rather than the achievement of an accord that could usher in the most mutually beneficial U.S.-Iranian relationship since 1979, the neoconservatives, their Israeli bedfellows, and not just Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and an indeterminate number of American Republican Members of Congress, prefer a continued standoff between Washington and Tehran. What is more, they would not rule out a forceful American confrontation with Iran and the undeniable potential for yet another disastrous armed conflict.

Returning to the Iraq War Playbook

The language is similar to the run-up to the invasion and occupation of Iraq that commenced in March 2003. To wit: Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell appeared on one of the most widely viewed Sunday talk shows on March 15 calling Iran’s government, “one of the worst regimes in the world.”

Much the same was said by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu during a March 3 address to a joint session of the U.S. Congress, echoing his 2002 testimony to the U.S. Congress in which he advocated attacking Iraq.

As was the case prior to their urging that the United States go to war with Iraq, opponents of an agreement with Iran have tended to couch their arguments in the deliberately seductive terms of providing serious and favorable consideration to using force to protect America’s, Israel’s, and the world’s alleged national security and related interests. Over a decade ago, the same rationales were expressed regarding pre-invasion Iraq. But while area studies specialists and scholars long exposed to Iraq’s history, culture, system of governance, political dynamics, armed forces, and foreign relations viewed the rationales as transparently bogus, many others were fooled.

The American result, to be sure, has hardly been cost-free. A reason is that the strength and weakness of any system of democratic governance turns on the consent of the governed, with the most informed consent typically following adequate and effective consultation. In the best of circumstances, consent and consultation are linked to the degree that citizens are able to make societally relevant judgments that are just, fair, and prudent. In this case, however, both processes have fallen short.

[pullquote]What those opposed to a mutually acceptable accord with Tehran have in mind bears a strong resemblance to the bill of goods sold to the American people in support of the U.S. effort to topple the regime of Saddam Hussein.[/pullquote]Twelve years after the invasion and occupation of Iraq commenced, notwithstanding the fact that commercially speaking some Americans have made out “like bandits,” the self-inflicted severe damage to U.S. interests stemming from America’s decision to attack the country has yet to be repaired.

Viewed in this light, the clamor to attack the Islamic Republic of Iran reads like a sequel for those who all along preferred that the United States invade Iran first and not Iraq. Indeed, dating from the mid-1990s onwards, America’s neoconservatives, their kindred citizen allies, and innumerable Israelis alike were known for wanting the United States to wage war against Iran. As for any and all others eventually to be attacked and their regimes toppled or brought to their knees – the neocon list included not only Iran and then Iraq, but also Syria, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia – America could change their governments later.

The Ultimate Neoconservative Wish List

Against this background, it is worth pondering what those who would have the United States confront Iran, with Israel’s strong support, would arguably like to achieve. Their wish list includes:

(1) Deflecting Attention Away from Israel,…

One of the most important neoconservative and Israeli objectives in having the United States attack Iran is to do whatever is necessary to shift the U.S. focus and notions of Israel’s culpability of wrongdoing away from the eastern Mediterranean towards lands east, e.g., Arabia and the Gulf.

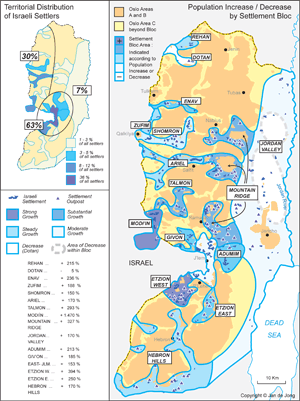

This would arguably absorb precious U.S. foreign policy energies, attention, and other resources on matters other than Israel for far into the future. It would likely squelch efforts to move as expeditiously as before to establish an independent State of Palestine. It would almost as surely deflect Washington from pressuring Israel into an early withdrawal from – and putting an end to the increase of – Israel’s illegal settlements in the Occupied Palestinian and Syrian territories.

(2) …Territorial Expansionism,…

This is what happened when Israel invaded Lebanon in June 1982. That act shifted Washington’s attention away from rigorously continuing to pursue the goal of a just, enduring, and comprehensive peace agreement between Israel and the Palestinians and towards Lebanon instead.

By the time Lebanon regained the lands that Israel had invaded and occupied directly and by proxy 19 years later, the Palestinian territory brought under Israeli control had expanded extensively and the Israeli settler movement had massively increased its numbers. Israel thereby achieved its illegitimate interests. In so doing, it blocked the legitimate interests of the Palestinians, Syria, Lebanon, the United States, and the rest of the world in resolving the Arab-Israeli conflict.

In keeping with the adage that “nothing succeeds like success,” consider how the strategy of deflection has similarly worked to Israel’s advantage in the wake of the American-led onslaught in Iraq – situated, like Iran, far to the east of Israel. In the intervening dozen years, with the United States additionally distracted by its further engagements in Afghanistan and its issues with Iran, Israel has proceeded to expand its illicit acquisitions of Palestinian territory. For example, it began in 2000 to construct its so-called Security Barrier, or The Wall, which cut deeply into territory previously designated for an independent State of Palestine. Subsequently the International Court of Justice, in a 14 to one Advisory Opinion vote in 2004, declared that unilateral act in conflict with international law. The wall continues to stand.

Consider simultaneously the continuing increase during this period in the promulgation of new housing units for settlers on Occupied Palestinian and Syrian land. Also consider the rise in the number of settlers. All three of these faits accomplis, each in conflict with international law, have occurred with the United States being preoccupied and operationally, logistically, and administratively stretched thin with issues pertaining to Afghanistan, Iraq, and Iran, and essentially doing nothing to prevent their occurrence.

With deflection continuously in play, all three outcomes in Israel’s perceived geostrategic and geo-economic favor have transpired alongside its refusal to accept the 2002 unanimous pan-Arab peace offering to Israel, which still stands. The proposal contains virtually everything successive Israeli governments have claimed and demanded they would have to have from Israel’s Arab neighbors and the broader Arab world in order to end the Arab-Israeli conflict peacefully and once and for all.

With no end in sight to the American-induced chaos in Iraq and no silencing of the war drums that remain directed at Iran, Israelis – in keeping with the strategic goals of deflection – have continued to find these kinds of realities convenient. Repeatedly and effectively such realities are cited as reasons for claiming that now is not the time to talk seriously about ending the country’s conflicts with Palestinians and Syrians.

Shunned has been the UN Charter. Shunned, too, have been long-standing global conventions that prohibit the threat or use of force and the acquisition of territory that way as well as principles upholding the right of peoples to self-determination. The principles are hardly ones of little consequence. They are ones that Israel has repeatedly acknowledged and officially accepted but, with the exception of Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula and the Gaza Strip, not implemented.

Deflection has worked. In the meantime, Israel has continued to enjoy and benefit from the practically unbridled support of the U.S. government. Nowhere has it garnered greater backing for its hardline positions against Iran and an early revival of the peace process than in the U.S. Congress. Many of its Members dare not raise a voice in protest against such behavior. To be sure, Israel’s strategy has achieved stunning results.

(3) …And Maintaining the Image of Threat

Simultaneously, by maintaining the perception of Iran as a pariah, neoconservatives and other groups have a better chance to preserve what they have conjured and built up in the mainstream American and other Western media as a recognizable “existential threat” to Israel. The imagery of such a threat helps sustain the narrative of Israel as a besieged bastion of victimhood rather than as a militarily powerful scofflaw inflicting brutal punishment on Palestinian Arab Christian and Muslim civilians. Doing so also assists in deflecting attention away from Israelis expropriating the Palestinian’s and Syrian’s land and exploiting their orchards, olive and citrus groves, and their water and other valuable natural resources in the Occupied Territories.

(4) Regime Change

Many believe that the goals of Americans and Israelis opposed to Iran are not to change the behavior of the regime in Tehran but, again as with Iraq, to change the regime itself. Those of this view seek an Iran that would be: more moderate in its approach to the Arab-Israeli conflict, less supportive of Hezbollah in Lebanon and of the Assad regime in Syria, and one that will have ended its intrusions into the domestic affairs of the GCC countries and Yemen, curbed if not reversed the degree to which it has eroded de facto the national sovereignty and political independence of neighboring Iraq, and terminated the nature and extent of its forceful aid to Hamas and Islamic Jihad in Palestine. These were among the exact same kinds of goals of the largely unstated American neoconservative and Israeli geostrategic, geopolitical, and related objectives vis-à-vis Iraq prior to the invasion in 2003.

(5) Protecting Privileged Status

Israel cannot take its relationship with the United States for granted and expect to compete effectively in the long run for America’s favor. This is why many Israelis believe they have no choice but to be strategically opposed to the strongest and most expanded possible American-Arab, U.S.-Iranian, and/or U.S.-Saudi Arabian relationship, let alone alliance, or the day when the United States may find itself in a reciprocally rewarding relationship with the GCC as a bloc to an even greater extent than it already enjoys with its six member-states. To wit: there are 22 Arab countries and only one Israel.

Tehran finds itself in a similar strategic predicament. Indeed, for nearly half as long as Israel has existed, Iran geopolitically has viewed its situation as nearly identical to that of Israel, and has reasoned likewise and often acted accordingly. That Washington might be on the verge of turning a new page with Tehran, which in time could lead to Iran being added to Israel among America’s most valued strategic partners – and bringing nearer the day when there might also be a rapprochement between Iran and Israel, as in days of old prior to the onset of the Iranian Revolution in 1979 – is for many in the GCC region a nightmare.

These dynamics periodically draw Israel and Iran together despite their denials. Many in both countries acknowledge that they need each other. As many consider the period since 1979 as an aberration. One of the most powerful illustrations of their two capitals dancing in each other’s strategic shadows and scratching each other’s back was their military and geopolitical collaboration during the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war.

The Israel-Iran-Contra affair revealed in November 1986 that Israel and Washington, under the Reagan administration, were providing arms to Iran despite Iranian agents and supporters holding American citizens in Lebanon hostage. That Israeli-American-Iranian collusion made the war last longer. It occasioned the killing of many more thousands of Iraqis vis-à-vis Iranians than would otherwise have been the case. It dealt a devastating blow to U.S. foreign policy needs. In keeping with Iranian and Israeli interests, it soured U.S.-Arab relations, miring them in suspicion, doubt, and distrust for an extended period.

(6) Financial Opportunity

Some see a different leadership environment in Tehran providing opportunities to construct what could be a golden gateway to Iran’s economy. The rationales undergirding this kind of long-term strategic thinking are, once more, in many ways similar to those that preceded the American attack against the regime of Saddam Hussein.

Not only could such an opportunity potentially help achieve numerous objectives of an economic, political, commercial, and military nature, as proved to be the case in Iraq. More particularly, it could help determine the uses to which Iran’s prodigious energy reserves in the future would be put fiscally, developmentally, and internationally.

Indeed, the financial, infrastructure, building, and material needs of Iran are immense, diverse, and a potential business bonanza for whomever will cash in after the international sanctions are lifted. To a greater extent than has been the case for a very long time, Iran should be able to grant American and other multinational companies’ access to its investment markets, banking system, and raw materials.

Tehran will also be in a much better position to decide the terms of foreign entry into the country’s national energy sectors, harbors, mega-infrastructure, reconstruction, and advanced exploration and production contracts worth billions of dollars once the government’s quasi-pariah status comes to an end.

For investors and strategic development planners, two other features of Iran, in an eventually and differently configured future, have the potential to function more as economic constants than variables. One, nowhere else along the entire eastern side of the Gulf – on the western side only Saudi Arabia approximates the same – does one country, as in the case of Iran, border landward or seaward as many as more than a dozen other nations. The resulting lucrative possibilities for forging multiple land transportation corridors and aviation routes from Iran to other destinations are limited only by the imagination. Once sanctions come to an end, Iran will have the potential for generating profits as yet undreamed of during the course of the past three and a half decades of relative economic isolation.

The second constant is demography. At a population of around eighty million and counting, Iran’s citizenry is more than twice that of Iraq. It is also substantially greater than the population of the entire number of inhabitants of the six GCC countries – citizens and non-citizens combined. In the eyes of would-be foreign investors and insider venture capitalists, whose perspectives are framed in terms of marketing consumer goods and services, and production, advertising, and distribution activities as yet unrealized, what these numbers could sooner rather than later come to represent are significant opportunities for financially rewarding relationships with Iranian customers, clients, and partners.

In Iran as elsewhere, there is certainly strategic value and a heightened prospect for achieving economic and commercial advantage in being near or at the head of the line for such mega-business as to be had.

(7) Energy

While some might view the recent onset of the international glut in petroleum supplies and exports as ruling out any energy-centric goal among the would-be forcible interveners in Iran – regardless of whether or not what they have in mind is regime change – there is merit in considering such matters from a longer-term perspective. Certainly, American and other major international oil and gas companies not engaged in Iran’s energy industries take this view.

As to why, consider the following. Iran is second only to Russia in proven gas deposits. In addition, few countries possess anywhere near the prodigious hydrocarbon reserves held in the Islamic Republic beneath its waters and sands. They exist in three separate and distinct areas: the Iranian mainland and two bodies of water. Among the latter, on one hand is the Gulf, with its accompanying coastline of more than 550 miles, longer than any six of the waterway’s seven other countries combined. On the other is the Caspian Sea.

The United States and Israel, moreover, are past beneficiaries of Iran’s bounteous energy resources. Both before and since the onset of the Iranian Revolution in 1979, Iranians, Israelis, and Americans were petroleum industry partners. Israel obtained ninety per cent of its oil imports from Iran through 1978. The United States stood to renew the nature and extent of its earlier benefits in 1995 and would have been able to do so had the American Israeli lobby not quashed a lucrative Iranian concession – valued at $1 billion – granted a major U.S. company to develop an offshore Iranian gas field abutting one administered by Qatar.

(8) The Naval Dimension

The Russian government and its predecessors for centuries have long sought direct access to a warm water harbor far to the south of the Russian mainland, and Iran has always been deemed ideal. In a future nearer than one might imagine Iran will determine who will have preferential access to its ports and who will not.

The Gulf’s long and ongoing relevance to global maritime interests – and Iran’s potential role in that relevance – ought not to be underestimated. For example, Iran has a growing ability, with what Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has described as a “strategic force,” to project naval influence in regions far afield, including the ability to provide weapons to its Hezbollah allies in Lebanon. Of additional importance in this regard is that Iran’s forces have the related capabilities to conduct asymmetrical naval warfare and threaten the freedom of navigation in the Gulf. National security analysts have also noted the possibility of Iran being able to use its maritime assets to import prohibited items for possible covert purposes in conjunction with further developments related to the reach of its long-range missiles as well as its nuclear program.

Further, Moscow no doubt appreciates that its warships have been welcomed at the Iranian port of Bandar Abbas near the Hormuz Strait. The ways in which the Russian Federation would be able to derive a variety of benefits in a differently ordered regional security architecture are numerous. They include scenarios in which the Russian Navy would be able to utilize Iran’s ports for purposes such as the prepositioning of supplies, conducting training, and, at some future date, participating in joint naval maneuvers. All of these possibilities can be viewed as enabling Moscow to extend its geopolitical and geostrategic power and influence further inside the Gulf and beyond into the Gulf of Oman, the Arabian Sea, and the Indian Ocean.

Meanwhile, the United States Fifth Fleet is home ported in GCC member-state Bahrain. From there, U.S. naval vessels operate continuously to ensure freedom of navigation throughout the length of the Gulf. They conduct surveillance, help to interdict smuggling operations, assist in countering piracy in the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean, and maintain vigilance towards GCC member-state Oman’s seaborne artery – through which passes a fifth of the world’s oil traded daily and near which units of Iran’s naval forces, situated directly opposite Oman, recently practiced attacking a replica U.S. vessel. All these international maritime, energy, trade, and commercial dynamics are as of a piece within a seamless web of self-evident challenges and opportunities that the United States has not left untended.

(9) Diaspora Dynamics

A quite different Israeli goal vis-à-vis Iran stems from the Islamic Republic being home to the last remaining significant Jewish population in the eastern Islamic world. With a view to how best to continue the ingathering into Israel of as many Jews as possible – note Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s reminder in the wake of recent attacks in Belgium, Demark, and France that European Jews would be welcomed in Israel “with open arms” – some Israelis muse about what an attack against Iran, regime change in Tehran, and/or Israeli agent-inspired attacks on or threats to the country’s Jews could accomplish. Some believe it could inspire significant numbers of Iranian Jews to want to relocate to Israel.

Here, too, is where important precedents are illustrative. An example is Iraq, albeit from an earlier era. In the late-1940s, Israel-inspired attacks against synagogues in Baghdad (that Israelis falsely blamed on Arabs) prompted large numbers of Iraq’s Jews to emigrate to Israel. If something similar was to occur in the wake of a war with Iran or even without it, the result eventually could help enable the current Jewish ethnic and religious majority in Israel to be better able to cope with the demographic challenge facing the country.

The increasingly high cost of living in the Jewish State and/or the wish of many of its citizens not to live with constant fears about the long-run prospects for the country’s survival could continue to spur the ongoing outflow of citizens from Israel. Already, an estimated one million Israelis are living in the United States and thousands more have returned to Germany.

Alternately, a more draconian scenario could enable the Jewish majority in Israel to remain in its numerically superior status. Israeli defense forces could respond to protests against an American and/or Israeli attack on Iran, citing heightened security concerns, by expelling significant numbers of Palestinians. The result could fulfill declarations by Israelis in support of population transfer, a phrase that masks the intent to ethnically cleanse the country of its Palestinian Arab Christian and Muslim inhabitants.

Electoral Dynamics

A perennial component in U.S. and Israeli domestic politics provides still further insight into how war with Iran – or even the fear, threat, or otherwise emotionally-charged aspects associated with it – might benefit Israel. The point is hardly academic. For example, as just occurred in Israel, American and Israeli special interest groups often seek to ascertain the extent to which candidates for public office in Israel – and in U.S. elections, too, every two, four, and six years – are more likely to keep Israel secure from radical Muslim Arabs and Iranians.

Election-related dynamics in either Israel or the United States ought therefore not to be taken lightly. They have the potential to determine not only whether but, if so, when Iran – or some other country alleged to be a threat to Israel – might be attacked. A precedent is 1981 when the Israeli attack on an Iraqi nuclear reactor was widely credited with enabling then-Prime Minister Menahem Begin, previously behind in the polls, to win re-election.

More than a few political philosophers over the centuries have advised that leaders who seek at all costs to remain in power in the midst of being challenged by strong domestic opponents seeking to replace them should consider taking their country to war.

Day of Reckoning Approaching

From an historical point of view, one can conclude that there is nothing strange about these kinds of motivations, agendas, and self-centric interests in favor of preventing six of the world’s most powerful and influential countries from reaching an agreement with Iran. Since recorded human history the propensity of mortals to covet other people’s assets, to do whatever is necessary to obtain them, and to engage in duplicitous and manipulative behavior in pursuit of strategic advantage and material gain at the expense of someone else is hardly new.

In the run-up to America’s and Iran’s day of reckoning there is therefore much to consider. At this time it is important to be clear about relevant matters that are not being discussed, let alone debated, in terms of America’s and Israel’s perceived needs, concerns, interests, and key foreign policy objectives.

At the very least, there is a need to ponder the implications of what is enumerated and examined herein with a view to reconciling them with logic, history, precedent, and prudence. Certainly, there is no reason for anyone to claim later that they were hoodwinked regarding the true nature of various American and Israeli interest groups’ largely unstated and unacknowledged goals and objectives in wanting to avoid a ground-breaking agreement with Tehran at this time and/or to bring down the Iranian regime, if necessary by force.

****************************

Dr. John Duke Anthony is the Founding President & CEO of the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations.

This essay was revised and expanded on March 26, 2015.