Saudi Arabia has begun administering the Kingdom’s boldest, most innovative, and farthest-reaching modernization and development plan in the country’s history. It addresses the near, mid-term, and longer-term needs and challenges that strategists believe the country is likely to face in the next fifteen years. Conceptualized and approved by the country’s leaders, the plan’s name is “Saudi Arabia Vision 2030.”

The plan reflects an extraordinary degree of extended research, analysis, and assessment. It was aided throughout by the input and comment of some of the world’s most renowned and experienced advisors in forward planning, focus, messaging, and communication. The process was launched in 2015 soon after Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques HRH King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Sa’ud appointed his son, HRH Prince Mohammed bin Salman, as Deputy Crown Prince and Minister of Defense.

In the eyes of his fellow citizens and the Kingdom’s inhabitants, Prince Mohammed is unique. A reason is not only because of his youth. He was 30 years of age on the day “Vision 2030” was officially announced in April 2016. Of special interest and in this century without precedent is that he has been entrusted to oversee, guide, and administer two of the country’s most strategically vital portfolios.

In one, in his position and role as Chairman of the Economic and Development Affairs Council, Prince Mohammed is tasked with protecting and advancing the material wellbeing of the Kingdom’s 30 million people. Not least among his challenges in this regard is how best to address the needs of the country’s burgeoning youthful citizenry. The nature and degree of unemployment among this segment of Saudi Arabia’s population is a matter of mounting and daunting concern, combined as it is with the goal of increasing dramatically the share of private sector and foreign investment involvement in the Kingdom’s economic growth.

The Deputy Crown Prince has also been assigned to head the country’s principal armed forces establishment. The Kingdom’s military is tasked with defending the Arab and Muslim world’s most important and influential country in a region that, to a greater extent than any in the past half century, is laced – not within the GCC region, of which it is an integral part, but immediately beyond it – with an unprecedented degree of tension and turmoil.

In this regard, in close association with his ruling family cousin, Second-in-Command Crown Prince and Minister of Interior HRH Prince Mohammad bin Naif bin Abdulaziz Al Sa’ud, Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed is responsible for aiding the King in his role as Custodian of Islam’s two holiest places, Mecca and Medina. Internationally and domestically, the two leaders are jointly expected to ensure the Kingdom’s ongoing national sovereignty, political independence, and territorial integrity.

Stated differently, the two leaders, assisted by Minister of Foreign Affairs HE Adel bin Ahmed Al-Jubeir, are the primary Saudi Arabians tasked with protecting the country and the legitimate interests of its people. These include first and foremost enhancing the Kingdom’s security, stability, and peace, without which there would be no prospects for prosperity. Were these three interconnected factors to be weakened or lost, the likelihood of the country being able to maintain its present standard of living, let alone strengthen and advance it, would be difficult if not impossible.

It is with regard to this first aspect of the Deputy Crown Prince’s responsibilities that the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations is pleased to provide an essay asking “Can Saudi Arabia’s ‘Vision 2030’ Get the Kingdom Off the Oil-Economy Roller Coaster?” The author is Dr. Paul Sullivan, a Council Non-Resident Senior International Affairs Fellow. Drawing on the courses he teaches on national security challenges and economic dynamics, and vice versa, at two of America’s leading institutions of higher education, Dr. Sullivan examines the nature and goals of as well as the necessary national material and human resources relevant to the Kingdom’s strategic development plan for the next fifteen years.

In keeping with National Council’s Analyses and Assessments series, of which this essay is a part, the author weighs the prospects for the Kingdom being able to manage and address “Vision 2030″‘s challenges effectively. In so doing, he sheds light on what in his view will be required to achieve even a portion of the plan’s stated goals. In the process, he provides an array of information about, insightful data on, and analysis and evaluation of the Kingdom’s economic development prospects that would otherwise be hard-to-come-by.

Dr. John Duke Anthony

Founding President and CEO

National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations

Washington, DC

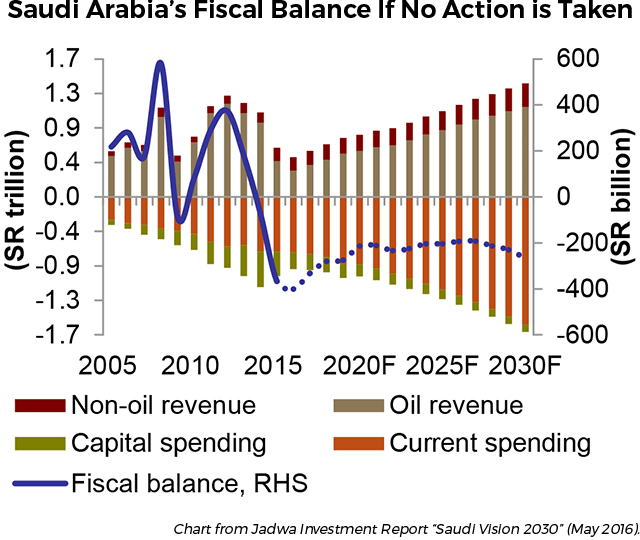

The Saudi Arabian economy is dominated by oil and has been for many decades. Oil accounts for about 35-45% of the GDP of Saudi Arabia. It is the source of 75-80% of its government revenues and 85-90% of its export revenues. Petrochemicals, based on oil and a much more recent component of the Kingdom’s economy than hydrocarbon fuels, are Saudi Arabia’s next largest export.

Saudi Arabia’s Oil-Economy Roller Coaster

At times in the past Saudi Arabia’s economy has been like a roller coaster. There was an economic boom due to the October 1973 Israeli-Arab war-induced oil embargo and the 1979 Iranian Revolution’s boost to the price for hydrocarbon fuels. This was followed by the collapse of oil prices and the resultant damage to the Saudi Arabian economy, which began in the early 1980s and continued until the late 1990s. As international oil prices remained stagnate throughout the better part of these two decades until the turn of the present century, so too, in many ways, did the Kingdom’s economy.

As prices began to ramp up in the 2000s, Saudi Arabia’s economy moved up with them until the Great Recession hit in 2008 when they collapsed for a brief period as the 2008 recession took its toll on markets. Soon after, however, prices rose to more than $100 per barrel in 2011, where they would remain until May 2014.

The most recent price collapse – from May-June 2014 until about January-February 2016 – was precipitous. The price since then, however, has risen, albeit in an unstable, bouncy, and slow manner. In short, Saudi Arabia has ridden the good times of oil price booms. It has also ridden the bad times when the price has collapsed.

Saudi Arabia has ridden the good times of oil price booms. It has also ridden the bad times when the price has collapsed.

The average Saudi Arabian’s income and wealth increased dramatically from 2002 to 2014. This was mostly due to the elevated level of oil revenues. The result was an increase in government spending and massive capital expenditures together with public sector investments.

Past Saudi Arabian economic improvements have started with a significant and sustained increase in the price of oil with concomitant increases in government and export revenues. These have been followed by large expenditures and investments in public sector ventures, with corresponding increases in imported labor, in Saudi Arabian employment, in massive building programs, and in contributions to the Public Investment Fund as well as, to a much greater extent, the Kingdom’s foreign reserves.

What will the price of oil be in 2017, 2020, 2025, and 2030? Who knows? It is very hard to predict. With the general slowdown in the world economy, including in Asia and especially in China, the international demand for oil is expected to be much flatter than in the recent past. In addition, the European Union and the United States are also expected to have slower growth patterns. India’s future expected economic expansion could give a boost to oil markets, but, if so, it will likely be muted compared to China’s boom years.

What is more, at the global level environmental and political interests are increasingly pressuring governments and people to move away from their reliance on oil for transportation. One is therefore likely to see greater use of natural gas-, electric-, and battery-powered automobiles, and, in time, buses and trucks, too. To the extent that these trends continue, one can anticipate corresponding improvements in vehicular efficiencies all around. For example, China will have far more automobiles than it has now, but the cars its people will be driving are likely to be more efficient and, eventually, use less oil. Coupled to the implications of these factors is the revolution in the oil markets caused by fracking and the development of other unconventional energy sources, with the corresponding change in the geographic centers of oil production.

A result of all these trends and indications is that Saudi Arabia and its fellow OPEC member countries have nowhere near the capacity they once had to influence the level of oil prices. Without any serious political events or physical attacks on major energy infrastructure facilities in various countries and especially in Saudi Arabia, which holds most of the world’s excess oil capacity, oil prices could creep up to $60 a barrel and then bump along between $60 and $80 for quite some time.

Challenges and Opportunities

Insightful in this regard is that Saudi Arabia needs an oil price of only about $10 to break even on the costs of producing a barrel of its oil. It needs the price to be over $100 per barrel, however, to break even on its government budget given its huge subsidies programs, the high costs of public sector wage bills, the social contract between the country’s monarchy and its citizenry to maintain domestic security and stability – a de facto contract that exists in one form or another between every government and its citizens – and the lack of any income or valued-added tax (VAT), although there is a zakat tax and a tax on foreign corporate profits.

Another consideration is that the country’s foreign assets, foreign currency reserves, and government budget have all been in free fall over the last couple of years as oil prices have tumbled. As a result, the Kingdom has recently reached out to world, regional, and domestic debt markets to help pay its public sector bills. To this end, a multi-billion dollar bond issue in the coming days, if and when concluded, will surpass that of Qatar’s as the GCC member-states’ highest in history.

In addition, public sector expenditures are being cut back and government employment opportunities for the country’s most recently minted university graduates look less promising than in years. There is even talk of some of the public sector bills being paid with IOUs and admission by government ministers of there being a discussion, but no agreed decision or agreed upon plan of action, to introduce taxation for expatriates. In almost the same breath, however, ministerial-level officials were quick to indicate in the strongest possible terms two things. One was that expatriates, who number roughly a third of the country’s 30 million population, remain an extraordinarily valuable component of the Kingdom’s populace and work force. The other was that there is as yet no intention whatsoever to levy an income tax on nationals.

Yet despite these challenges it would be a mistake to conclude or even consider that the Kingdom is or will soon become an overly problematic proposition insofar as matters pertaining to trade, investment, the establishment of profitable joint commercial ventures, and business opportunities in general are concerned – certainly in comparison with the 130 other developing economies and emerging markets, or many among the world’s so-called mature industrialized and market economies either. Further, the government and the public sector in general, including the still young stock market and stated plans to privatize. Indicative of the latter inclination is the officially declared intention to sell a piece of Saudi Aramco, whose value is estimated to be in the neighborhood of two to twelve trillion dollars. All in all, the country therefore still has numerous extraordinarily lucrative assets, hundreds of billions of dollars in foreign reserves, and perhaps 800-plus billion barrels of conventional oil in the ground.

In addition, the Kingdom possesses massive mineral assets such as gold, bauxite, and iron, and vast numbers of beaches, islands, and diving areas in the Red Sea that are acknowledged as among the best to be found anywhere. Add to these riches Saudi Arabia’s innumerable cultural, historical, and religious sites, an increasing collection of world-class museums, and an array of yet-to-be explored, drilled, or mined areas of bountiful deposits of material riches that surpass what is known to exist anywhere else in the Arab countries, the Middle East, and the Islamic world. What is more, on the alternative energy economic driver front, Saudi Arabia has substantial opportunities in solar, wind, geothermal, and other kinds of renewable energy resources. In sum, the country has massive potential for economic diversification and growth as well as tourism and a yet-to-be-fully developed reservoir of first-rate and well-educated human resources.

Saudi Arabia’s Labor Force

Beginning with the late King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz, the impressive 23-25% of Saudi Arabia’s budget that in recent years has been appropriated annually towards education – at the time a world record – is likely not expected to yield the impressive returns envisioned until perhaps half a decade or more. With the late King Faisal’s reformist educational program from 1963-1975 as a frame of reference, it takes a minimum of twelve years to produce a differently and more scientifically and technologically educated person to even begin to be able to display the results of the investment in her or his education, training, and other development. With the launching of the King Abdullah Scholarship Program, of which more than twenty percent is comprised of female students, there are already reports of a marked increase in the number and comparative percentage of the Kingdom’s youth who complete the full four years of their university education. Still, about 50% if those who start college in Saudi Arabia opt not to complete their studies or are unable to fulfill the requirements for the degree and, thus, fail to graduate.

As matters stand, only about 30% of Saudi Arabians who could be part of the labor force are working. This has a lot to do with the ongoing impact of historical experience and cultural as well as societal norms against the employment of women, the limited number of childcare facilities at workplaces, inadequate public transportation options, and the fact that women cannot drive, which for outsiders and especially Americans, has long been and remains a deeply misunderstood cultural aspect of the Kingdom, but still a limitation to women’s employment.

A different set of challenges lies in varying levels of remuneration depending largely on the economic sector in which one is employed. For example, wages and benefits in Saudi Arabia’s public sector are considerably greater than in the private sector. A big boost to these came when HRH King Abdullah gave all government workers a large raise in 2011. The reason was twofold. One, it was ostensibly in order to reduce what might otherwise have been pressures on Saudi Arabia from the growing severe unrest in neighboring and nearby countries, referred to at the time as the “Arab Spring.” The second reason was because the Kingdom’s treasury could then afford to do so.

The government’s massive wage bill has limited the country’s ability to move forward with other expenditures that, before the oil price plummeted, had considerable potential for ensuring a robust economy for some time into the future. Given the fairly low productivity of Saudi Arabia’s public sector employment and its relatively high wages, one could argue that this is a source of considerable economic waste.

Most of the workers in Saudi Arabia’s private sector are contract labor expatriates from South Asia and, to a lesser extent, other parts of the Arab world. It has long been the case that many male Saudi Arabians are averse to the jobs that contract expatriates have due to negative social perceptions regarding the nature of the work, the comparatively lower wages, the longer hours, and fewer holidays. It should therefore not be surprising that there are long waiting lists for government jobs.

A related but somewhat different challenge is that achieving the national goal of employers “Saudizing” their work force remains elusive. Indeed, the continuity of comfort, which continues to be seductive, constitutes a formidable reality. That is, with it still being more economically profitable and productive to hire and retain workers from other countries who are willing to work harder and for longer hours, less pay, and fewer benefits, Saudization of the country’s private sector employees is far from resolution. Indeed, it is likely to remain a substantial challenge for some time yet to come. Consequentially, tens of billions of dollars flow out of Saudi Arabia in remittances each year.

But with regard to the economic results and ramifications rooted in remittances, is this the end of the story? No, it is not. A reason is that a case can be made that the billions of dollars leaving the country annually are not as damaging as might at first glance seem to be the case. That is, they are partially offset through the gains generated by the Kingdom’s merchants, vendors, and landlords. These derive, respectively, from the value and volume of capital goods and consumer items that foreign workers purchase from local sources to take to their family back home at vacation time or when their employment is terminated. Additional gains can be calculated from the net value of the food and other necessary living expenses that expatriates buy from local sources and the rent that many pay for their accommodations. On balance, however, while it is hard to determine what the total value of these numerous and diverse offsetting factors may be, the sum is likely far less than that of the remittances leaving the country.

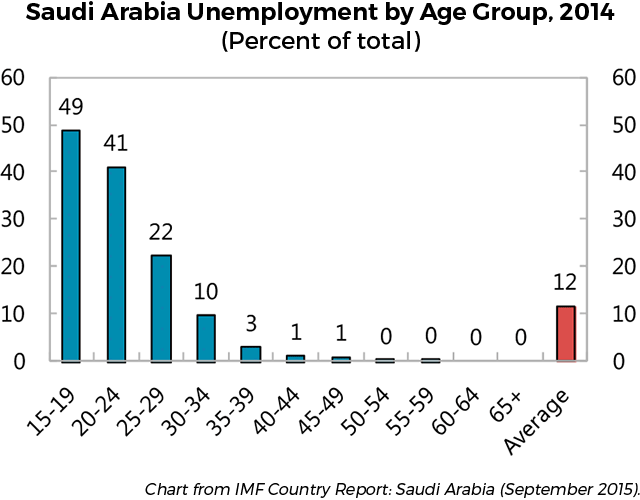

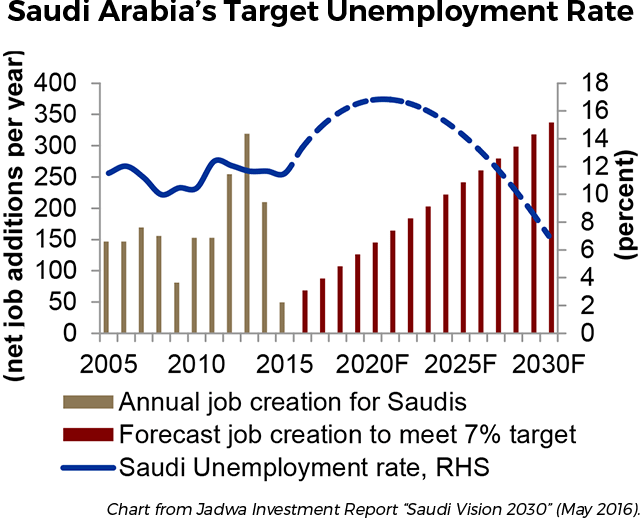

The pool of young women and men scheduled to enter the Kingdom’s work force in the coming years, already large, is growing. About 60% of Saudi Arabians are under the age of 30. Official unemployment for Saudi Arabians is about 12%. Underemployment is likely much higher. Youth unemployment (15-25 years old), however, is about 43%. For those in the 15-30 years old age bracket it could be as much as 35%. Jobs need to be created – and created quickly and smartly – that are as productive and as satisfying as possible.

The pool of young women and men scheduled to enter into Saudi Arabia’s work force in the coming years, already large at present, is growing.

There are many more Saudi Arabian women in the work force, and many more men as well, than there were in the 1990s. There are disconcerting disconnects, however, between skills, capabilities, education, and training, on one hand, and Saudi Arabia’s employment needs, on the other. This is especially so amongst women who, for quite some time now, have been more likely to finish their college education than men, and, in keeping with female students the world over, are in many circumstances likely to earn better grades. However, on balance, unemployment and underemployment among Saudi Arabian women is massive and a substantial loss to the Kingdom’s economy.

These realities would seem to indicate that Saudi Arabia’s status quo is unsustainable. If so, the likelihood is that if the same economic and incentives system remains in place, unemployment and underemployment in the country would be destined to worsen along with associated social pressures.

Navigating Reforms

Tempering the economic realities of large numbers of the Kingdom’s citizens are the nature and extent of benefits that do not exist for most elsewhere in the world. Depending upon the individual in question, these can amount to very large sums of money. For example, for millions of citizens and also vast numbers who are not, there is no or only minimal cost for education from kindergarten all the way through a doctorate degree, regardless of whether completed in the Kingdom or abroad. Also, books, school lunches, many medicines, basic health care, and legal services are free. Additionally, until very recently, the fees for water, electricity, sewage treatment systems, and gasoline were some of the lowest on earth.

Such benefits include what, half a decade ago, would not have been expected. These are the cost of arrangements necessary to accommodate and provide the same kind and range of benefits to some 2.5 million Syrians displaced by the war in their country. In this regard, for religious and humane reasons related to preserving people’s dignity, it is important to recognize that these Syrians are not “refugees.”

On the other hand, the manifold, multiple, and excessive subsidies and other economic distortions in place are very costly, especially during the down hills in the economic roller coaster. When subsidized oil is used to make fresh water, some of which is used to grow subsidized agricultural products, the economic costs of these government benefits grow quickly. And like subsidized goods and services practically everywhere, they can lead to excessive energy, water, and food waste. However, regardless of how a country’s planners and plan administrators may find such an option compellingly attractive, reducing or repealing these subsidies needs to be done very carefully in order to not cause civil disruption.

Saudi Arabia is also in the midst of a costly war in Yemen and involved in other regional conflicts. It imports almost all of its military and most of its domestic security technology and equipment, valued in the tens of billions of dollars – a massive expense. Many think that the Kingdom’s defense and security establishments and their procurement sections could be far more efficient and economical. This said, there is no denying that the country’s national security will continue to depend greatly on the power, development, transformation, innovation, and creativity of its economy – and the more so given how dangerous and volatile its neighborhood is.

That Saudi Arabia and its economy have unused potentials would be a stark understatement. Few if any doubt that the Kingdom could use its natural endowments more effectively by focusing on greater value-added in oil, gas, minerals, natural resources, and labor. Specialists, too, believe the country could increase its wealth and have less economic variability and social strife were it to have a more diversified, flexible, innovative, educated, and better-managed economy in its private and public sectors.

To their credit, the Kingdom’s leaders acknowledge that the country’s efficiency gaps, budget gaps, value-added gaps, human capital gaps, and other gaps must be addressed. They also understand how important their economy is to their national security.

Saudi Arabia Vision 2030

So what can make for a better Saudi Arabian future? One answer being developed is “Saudi Arabia Vision 2030.” It is a breathtakingly ambitious plan. Many question its chances for success. Yet even if it reaches 60% of its goals by 2030, this would put the Kingdom on a much more solid economic, social, and political footing than otherwise. Given the circumstances, the country has little choice but to work for such changes. Its leadership understands that continuing to ride the oil-economy roller coaster is not the best path forward.

The Kingdom’s leaders acknowledge that the country’s efficiency gaps, budget gaps, value-added gaps, human capital gaps, and other gaps must be addressed. They also understand how important their economy is to their national security.

So what is being planned? Saudi Arabia Vision 2030 is a complex program. Among the most important changes intended are to move the Kingdom’s economy from the worlds’ 18th largest to 15th, reforms to enhance economic competitiveness, increasing the private sector from 40% to 60% of the economy, and growing non-oil government revenues by over 10 times.

The program seeks to improve the workings of the government and cities, to dramatically diversify the economy, to increase the importance of small to medium-sized businesses from 20% to 25% of the economy, and to vastly increase foreign direct investment. It wants women to grow from 22% of the workforce to 30% and to increase the capacity for Umrah and Hajj visitors as well as other religious and non-religious tourism. It wants to increase the savings of Saudi Arabians, to make the country less consumption-oriented and more investment- and production-oriented. The program seeks to raise life expectancy by 6 years and reduce unemployment by over 4%. The goal is also to increase the development of non-governmental organizations and promote volunteerism. Broadly, the objective is to better connect the economy to education and training.

“Saudi Arabia Vision 2030” seems to want to transform not only the economy but also the citizenry – and in a short 15 years. The program plans to partly pay for this from a public offering of about 5% of Saudi Aramco, depositing the proceeds from the sale into the Kingdom’s Public Investment Fund. It also intends to place Saudi Aramco and numerous other public assets into a holding company that would promote development and transformation. Selling additional and possibly quite substantial public assets could also be in the works. If so, the goal would be to create a massive investment fund that would help introduce to the Kingdom effectively the nature and extent of the changes that the program envisions.

From some conservative elements there is already considerable resistance. As is to be expected, and indeed occurs in any and every country whenever leaders seek to alter the status quo, naysayers in this instance can be found inside and outside of Saudi Arabia. Some, certainly, naturally fear change. Yet others want to see these ambitious programs attempted and to succeed, even if only on a 50-60% scale, because the alternative to no change could be quite difficult for the country and the region. And as is inevitably the case and seemingly unavoidable whenever and wherever the goal and challenge is one of profound transformation, the hardest part will be the plan’s implementation.

Writing up plans is relatively easy. Making them succeed requires smart and hard work as well as creativity in leadership and thinking. In this regard, expectations management and strategic communications will be key. It is also vital that the changes occur in the context of and with all due consideration for Saudi Arabia’s society and norms.

Changing too quickly could have one or more less than desirable if not also contradictory consequences. In one scenario, it could shatter the very things that “Vision 2030” hopes to strengthen and expand. Another, no less significant, concern is that for one reason or another it could prevent curbing or rationalizing, let alone eliminating, the extensive and wasteful range of subsidies that preclude recovering anywhere near the actual costs of electricity, fuel, water, and a range of other of public services.

A Saudi Arabian recently spoke to me of how the Kingdom’s mosques could be helpful in promoting steps towards change and successful reform of the economy, government, and more. Change that helps people, he emphasized, could be seen as Islamic change. Change to use resources more efficiently and with less waste could also be seen as Islamic. Importantly, as stated in the Koran:

“Indeed, Allah will not change the condition of a people until they change what is in themselves.” (The Thunder, Sura 13: 11)

Change in Saudi Arabia needs to be a truly national project with buy-in from significant segments of the population as well as leaders from across the political spectrum. This is a momentous inflection point for Saudi Arabia’s future. It needs to be done right, and it needs to be done with consideration to Saudi Arabian culture and Saudi Arabian society.

All opinions are Professor Sullivan’s alone.

Author

-

Dr. Paul Sullivan is Senior International Affairs Fellow at the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations. He is also Professor of Economics at the National Defense University; Adjunct Professor in the Security Studies Program at Georgetown University; and Adjunct Senior Fellow for Future Global Resource Threats at the Federation of American Scientists.