On October 18, 2013, Saudi Arabia turned down a hard-won invitation to join the United Nations Security Council. Riyadh’s rejection of the much-coveted seat on the world’s highest deliberative body was described by many Americans in highly unflattering terms.

The decision comes in the wake of Saudi Arabia’s long-serving Minister of Foreign Affairs, HRH Prince Saud Al Faisal, opting to forgo deliverance of what for decades had been his annual address to the United Nations General Assembly.

Following the announcement, the Kingdom’s Chief of General Intelligence and Secretary-General of the National Security Council, HRH Prince Bandar bin Sultan, expressed his heightened concern about the state of the Saudi Arabian-U.S. relationship.

At the 2013 Arab-U.S. Policymakers Conference days after the kingdom declined membership on the Security Council, HRH Prince Turki Al Faisal, a prominent member of the kingdom’s monarchy, quoted numerous derogatory comments that U.S. opinion writers have used to describe the country’s actions and the reasons given for its decisions in this regard.

Some Perspectives

More seasoned commentators provided background and context for what occurred.

Some cited the kingdom’s profound disappointment at the Council’s recent inability, lain at the veto-wielding feet of mainly China and Russia, to bring an end to the continuing bloodshed in Syria.

Others agreed but added Saudi Arabia’s astonishment and anger at the way the Obama administration was so quick to turn its back on Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak.

Additional commentators noted the country’s long-held concerns over the spread of weapons of mass destruction in the Middle East, including both Iran’s developing nuclear program and Israel’s stockpile of nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction.

HRH Prince Bandar bin Sultan, Saudi Arabia’s Chief of General Intelligence and Secretary-General of the National Security Council, with Russian President Vladimir Putin. Photo: Russian Federation.

Further commentators remarked on Saudi Arabia’s frustration over the perceived naiveté of the United States in moving to open a dialogue with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani despite Iranian meddling in the affairs of GCC countries, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, and Yemen – this, after the gift of Iraq to Iran as a direct result of the U.S.-led invasion and occupation of Iraq against the advice of Riyadh and the capitals of most of the other GCC states, plus the envisioned possibility that the United States might somehow eventually reach one or more agreements with Tehran at the kingdom’s and its fellow GCC members’ expense.

Still others cited Riyadh’s ongoing deep disenchantment with the continuing tragic consequences of the Security Council’s larger, more pervasive, and continuing failure, lain primarily at the veto-wielding feet of the United States, to settle the much older conflict between Arabs and Israelis.

Given the number, nature, and magnitude of the Security Council’s noted failures and shortcomings, what Riyadh did — the negative comments of critics notwithstanding — was hardly petulant.

If Not to The Security Council, Then Where and Why?

What the kingdom decided was that the better course of action would be, first, to disassociate itself from the Council veto-wielders’ likely repeated failure to exercise their U.N. Charter-granted rights, leadership, and duties to promote peace.

Second, the kingdom’s representatives contended it would be wiser to place some distance between itself and the leaders who have effectively opted consistently to paralyze an otherwise noble and extraordinarily important institution.

Otherwise, the kingdom’s decision makers reasoned, they would risk conveying a message it did not believe: namely that the institution’s three most important leaders were likely, on what would have been the kingdom’s watch, to live up to what is expected of them by virtually all of the world body’s 190 other members.

But one might ask, with regard to exactly what expectations? The answer: the Security Council’s obligations – its duty, its responsibility — to do whatever possible to prevent the outbreak or prolongation of international conflict. In both cases, Syria and Palestine-Israel are at once the most recent and oldest examples.

Assessing the American Assessment

Was the kingdom wrong to do what it did? An initial response to the question is no; that is, not if one agrees with the factual basis of the kingdom’s complaints.

Upon further examination, the answer, in keeping with the adage that all politics are local, is also no; that is, not if doing so enables Riyadh to avoid being lambasted domestically for being perceived as ineffectually linked to the non-performance of an institution regarding issues and interests involving elemental justice pertaining to Palestine and Syria that it considers vital to its near- and longer-term security.

And not if opting to forgo being associated with the perceived forfeiture of statesmanship by Beijing, Moscow, and Washington enhances Riyadh’s contention that allowance of the immense human tragedies of Palestine-Israel and Syria to continue threatens regional and global stability alike.

It is in this light, the kingdom’s foreign policymakers contend, that critics are guilty of “not having been listening” to the grounds for their decision. If they have, the evidence, in Riyadh’s and many others’ view, suggests that what Saudi Arabians and the representatives of millions of other Arabs and Muslims as well as Europeans, Africans, Latin Americans, and Asians of different cultures and faiths have been trying to tell America, to the extent it has been listened to, has fallen on deaf ears.

Whistleblowers’ Lament

Yet, as is often the case whether with domestic or international leaders who log complaints against others regarding their public policy or behavior, it has not been China, Russia, or the United States that has been called on the carpet.

Instead, it is Saudi Arabia that has been singled out for criticism and disparagement bordering on ridicule. Once again, the whistleblower, not the wrongdoer, is assigned to take the heat.

In any event, in its opting for its diplomats to refuse an institutional seat alongside their American, Chinese, Russian, and other counterparts, how does one fairly assesses and pass judgment on the kingdom’s actions?

Responsibility Examined

Saudi Arabia has been likened by many to be a continent more than a country given that it encompasses an area larger than all of Western Europe combined and has a total of 13 neighbors. Map courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin.

In answer to the question as to whether and, if so, to what extent, if at all, can one accurately conclude that Saudi Arabia in this case acted irresponsibly, the first answer is no; that is, if one believes that friends don’t let friends drive when they are drunk.

The second answer is also no; that is, if one’s partners are deemed demonstrably unable or unwilling to act responsibly and effectively in matters of life and death to others such as Palestine and Syria definitely are to Palestinians and Syrians in addition to the inhabitants of Saudi Arabia and many other countries and peoples.

Given that much of the criticism directed at Saudi Arabia is coming from the United States, the UN Security Council member with which Riyadh has long had its closest relationship, does this seemingly controversial diplomatic imbroglio have a precedent?

Precedents?

In life in general, few so-called precedents are exact mirror images of other ones however seemingly identical they may at first glance appear on the surface. Like snowflakes and fingerprints, no two are the same. That said, there have been numerous occasions in the past when American and Saudi Arabian needs and priorities were at loggerheads and the public airing of their respective different viewpoints was laced with acrimony at both ends of the relationship.

Several examples come to mind. For Saudi Arabia, as well as for hundreds of millions of other Arabs and Muslims, the deepest wound dates from 1947 and has to do with what the United States did and did not do with regard to the United Nations Mandate over Palestine.

Over widespread Saudi Arabian and other Arab and Islamic opposition, the United States prevailed in what representatives of the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims to this day consider one of the world’s most unjust acts of the twentieth century.

Original Sin Revisited

From the kingdom’s perspective, the grounds for its conclusion are incontestable. For example, consider the following two points.

One, at the time, whereas over 94 percent of the land was owned by Palestine’s Arab Christian and Muslim inhabitants, under 6 percent of the country’s landowners were Jewish.

Two, while more than 60 per cent of the population was Arab, less than 40 percent was Jewish.

Despite these two realities, the United States proceeded to prevail in insisting that other UN member-states join it to ensure that 54 per cent of the land in Palestine, including the most arable and strategic territories, was given to its Jewish inhabitants.

Widespread Arab and broader Islamic world dismay at Western and specifically American complicity in the magnitude of the injustice perpetrated then knows no bounds.

As one respected international public opinion poll after another has documented, U.S. complicity in prolonging the Arab-Israeli conflict – the United States, in Arab eyes, has never missed an opportunity to miss an opportunity to bring effective closure to this conflict – has long been and remains the number one cause of anger among Arabs at American foreign policies.

Righteous Anger’s Manifestations

In Saudi Arabia’s case, the manifestation of its long simmering anger has not consistently, but frequently enough, erupted. When it has, it has sometimes been in the form of its participation in the embargoes of Arab oil to the United States and other Western countries. In each instance, the reason given was these countries’ de facto support for Israel’s armed conquest of Arab lands in Egypt, Palestine, and Syria.

Usamah Bin Laden and September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks mastermind Khalid Shaikh Muhammad repeatedly served notice that this one particular issue, among other ones, lay at the root of their and their followers’ determination to punish America and, by extension, its allies.

HRH Prince Turki Al Faisal at the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations’ Annual Arab-U.S. Policymakers Conference in Washington, DC. Photo: NCUSAR.

As Saudi Arabian Prince Turki Al Faisal said, speaking at the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations’ Annual Arab-U.S. Policymakers Conference last week, “Israel’s unwillingness to cease its unlawful colonization and continual refusal to grant the Palestinians their own homeland is the core reason that this conflict continues.”

At the conference Prince Turki also sharply rebuked American responses to developments in Egypt and Syria, saying that “[t]he current charade of international control over [Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s] chemical arsenal would be funny if it were not so blatantly perfidious, and designed not only to give Mr. Obama an opportunity to back down, but also to help Assad to butcher his people.”

“Land of the Free, Home of the Brave”?

Countless Saudi Arabians and other Arabs and Muslims have continuously pointed out how the Palestinian cause, representing in their view a betrayal of American values of freedom and the absence in this particular case of its courageous application of moral principles on so many other issues, has long been and continues to be the number one recruiting device for jihadists.

No other issue, Saudi Arabians and millions of others are persuaded, lies at the root of the motives of those committed to wreak destruction against the United States, American individuals and interests, and America’s friends, allies, and strategic partners in the Arab world.

The essence of this injustice, coupled with the strong U.S. de facto support for its continuance together with Washington’s complicity, by providing the Jewish state protection from effective censure and the implementation of specific Security Council resolutions by use of the veto in rewarding Israel’s “acquisition of territory by force” – specifically and literally prohibited by the UN Charter and American-brokered UN Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338 – are, short of a comprehensive, just, and enduring settlement, likely to remain at the core of Muslim anger at the ineffectuality of this important component of America’ foreign policies.

No Descent into the Abyss

Even so, a dispassionate and clinically detached observer might note, Saudi Arabian and other Arab and Muslim anger at the United States over this perennial issue has not caused a rupture in the bilateral relationship.

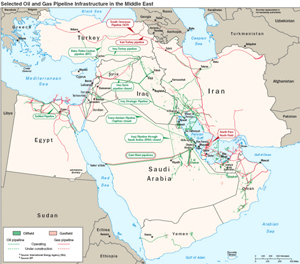

Distribution of Saudi Arabia’s existing energy reserves and infrastructure. One of Saudi Arabia’s oil fields contains more oil than all of the oil in North America and Europe combined. Map courtesy of the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Neither have half a dozen other contentious issues. Among them are (1) Riyadh’s participation in the Arab embargo of oil exports to the United States in reaction to what America did and did not do in response to the Israeli invasions and occupation of Egypt in 1956; of Egypt and Syria in the June 1967 war; and again in October 1973 when Egypt sought to regain the territories that Israel had seized in 1967; (2) Israel’s invasions and occupations of Egypt that resulted in the closure of the Suez Canal in 1956 for nearly a year and its closure again in June 1967 for nearly eight years; and (3) the Congressional difficulties and insults the kingdom had to endure in its efforts to purchase F-15 fighter aircraft in the late 1970s and again in the late 1980s.

Among them also are (4) Washington officialdom’s anger at Saudi Arabia’s refusal to support Egypt’s decision to sign a separate peace treaty with Israel in 1979 despite Israel’s remaining in illegal occupation of 1.5 million Palestinian Arab Christians and Muslims; (5) the failure of the Reagan administration in 1985 to sell the kingdom advanced defensive weaponry, resulting in Great Britain selling the Tornado fighter aircraft, which cost the United States some 60 billion dollars in lost revenue and the loss of what would have been thousands of new American jobs plus the extension of thousands of existing jobs; and (6) U.S. Congressional hearings that revealed the United States actually profited financially from the kingdom for having defended it in the course of reversing Iraq’s 1990 aggression against Kuwait.

And last but not least, among them also is (7) the spike in American anti-Saudi Arabia sentiments following involvement of the kingdom’s nationals in the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001.

Anyone who lived through some or all of these earlier imbroglios, that seemed destined at the time to rent the special American-Saudi Arabia relationship asunder, know that in the end the relationship remained not only exceptionally healthy and the envy of every other country but went from strength to strength to an overall extent that, at moments when it seemed to many that the two countries were headed irreversibly in opposite directions, few if any would have imagined.

Why the Staying Power?

If one asks why, the reasons include the following.

It is because the special relationship between the two countries is now more than seventy years old and counting.

It is because both sides have invested too much in the way of time, effort, and resources in the course of building and maintaining the relationship for either side to seriously contemplate disrupting the ties that continue to bind the two countries and their respective legitimate needs, concerns, interests, purposes, and foreign policy objectives.

It is because both sides have repeatedly acknowledged the relationship as simply too mutually beneficial to break or reduce the reciprocal strategic, economic, trade, defense cooperation, and people-to-people relations rewards deriving from it.

The conjoined flags of Saudi Arabia and the United States signifying the bilateral relationship between the two countries’ governments and their respective peoples.

It is because the level of American investment in the kingdom exceeds that of the rest of the world’s investments on one hand and, on the other hand, the United States benefits from having the bulk of Saudi Arabia’s foreign bank deposits, its investments in American corporations, its holdings of official U.S. Treasury and other U.S. debt instruments, and its having rescued the once-severely ailing Citibank, the worlds’ largest financial institution. In a similar vein, the United States benefits from Saudi Arabia’s purchases of tens of billions of dollars in American-manufactured defense and security structures, systems, ammunition, spare parts, and maintenance services that help to extend the life of U.S. industrial production lines and provide jobs for millions of Americans, all of which has contributed and continues to contribute to the globally-envied standard of living and overall material well-being of millions of Americans and their families.

It is because the degree of cooperation between the two countries in working to curb money-laundering schemes and the uses to which funds from either country can be put by extremist groups, together with the nature and extent of shared real-time analysis of sensitive intelligence of possible relevance to individuals and groups inclined to physical violence for political ends, exceeds that which exists between the United States and any other country, including America’s oldest and closest allies.

It is because the number of joint commercial ventures between American and Saudi Arabian corporate entities is greater than the number of all the rest of the world’s private sector-to-private sector joint business endeavors combined.

It is because of the deepening and broadening of interpersonal ties between the two countries as evidenced by the first-ever American female and male students enrolled at the new King Abdullah University of Science and Technology on one hand and, on the other, more than 72,000 full tuition-paying Saudi Arabian students — thousands of them women as well as members of minority groups — presently enrolled at American universities who, together with their 9,000 dependents, have contributed and are continuing to contribute significantly to the economies of the communities where they are studying and living.

It is because of the little known but jointly acknowledged year-round strategic dialogues between Riyadh and Washington on topics ranging from economics and cultural exchange to technology, security, and defense cooperation as well as the sharing of their respective geo-political needs and concerns, inter alia, which in the past year have been expanded to include a mutually long-sought dialogue on the same topics between the United States and virtually all six of the GCC countries

It is because both sides are keenly aware that the closeness and degree of trust built, galvanized, and sustained between them over such a long period of time is the envy of every other country.

It is equally their respective awareness that any number of the world’s other countries would happily and rapidly trade places with either of the partners were one or the other to grow tired of the relationship.

And finally, it is because of something that among bilateral relationships between any two countries is a rarity in the history of international affairs: namely a deep and profound awareness among each side’s leaders and increasing numbers of their respective citizens that the relationship has resulted in enormous benefit not only to each of the partners and their allies but to the rest of the world as well.

****************************

Dr. John Duke Anthony is the Founding President and Chief Executive Officer of the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations, and currently serves on the United States Department of State Advisory Committee on International Economic Policy and its subcommittee on Sanctions. On June 22, 2000, on occasion of his first official state visit to the United States since succeeding his late father, H.M. King Muhammad VI of Morocco knighted Dr. Anthony, bestowing upon him the Medal of the Order of Ouissam Alaouite, the nation of Morocco’s highest award for excellence. Dr. Anthony is the only American to have been invited to each of the Gulf Cooperation Council’s Ministerial and Heads of State Summits since the GCC’s inception in 1981. (The GCC is comprised of Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates).

Dr. John Duke Anthony is the Founding President and Chief Executive Officer of the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations, and currently serves on the United States Department of State Advisory Committee on International Economic Policy and its subcommittee on Sanctions. On June 22, 2000, on occasion of his first official state visit to the United States since succeeding his late father, H.M. King Muhammad VI of Morocco knighted Dr. Anthony, bestowing upon him the Medal of the Order of Ouissam Alaouite, the nation of Morocco’s highest award for excellence. Dr. Anthony is the only American to have been invited to each of the Gulf Cooperation Council’s Ministerial and Heads of State Summits since the GCC’s inception in 1981. (The GCC is comprised of Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates).

For more information access the National Council’s website: ncusar.org.

Read more from Dr. Anthony at: ncusar.org/pubs

Pingback: From Arabia to Asia: Does a Policy Shift Make Sense? | Arabia, the Gulf, and the GCC Blog

Pingback: From Arabia to Asia: Does a Policy Shift Make Sense? (Pt2) – Anthony | SUSRIS

Pingback: From Arabia to Asia: Does a Policy Shift Make Sense? (Pt2) – Anthony | ArabiaLink

Pingback: The Gulf Cooperation Council: Deepening Rifts and Emerging Challenges – Anthony | SUSRIS

Pingback: The GCC: Deepening Rifts and Emerging Challenges – Anthony | SaudiBrit

Pingback: The Return of Strong GCC-U.S. Strategic Relations | Arabia, the Gulf, and the GCC Blog

Pingback: Answering President Obama’s “Free Riders” Allegations — Arabia, the Gulf, and the GCC Blog

Pingback: The Gulf Cooperation Council: Deepening Rifts and Emerging Challenges — Arabia, the Gulf, and the GCC Blog