Arriving in the Sultanate of Oman you feel as if you are on a Hollywood set. Orderly. Vast. Visually breathtaking. Often visitors liken it to Disneyland. Controlled. Well-organized, meticulously maintained public grounds. Friendly. Happy. Helpful. Tolerant. No litter. No vagrancy. No graffiti. No terrorism. No violence. No radicalism. No unsafe areas. Did I mention exquisitely clean…It is all this and more.

Oman is an Arabian dreamscape. I’ve never seen such well-planned urban development. Architectural details are carefully mandated here. Many of the buildings are 46 years young; they’re well thought out in placement and accessibility. Even the street lamps in the cities and on the highways are lyrically beautiful in their repetitive form. There is something calming and reassuring about this consistent elegance.

The Public Authority for Investment Promotion and Export Development building in Muscat.

This tranquility is the hallmark of the capital city of Muscat. Muscat means “place of anchorage.” There you find a visual feast of stylish, controlled, and unified structures that underpin the deliberately skyscraper-free skyline. Here a hyper white Arab style of architecture is juxtaposed against the rough rocky landscape of the Hajar Mountains and the blue Gulf of Oman. Oman is an architectural treasure in Arabia.

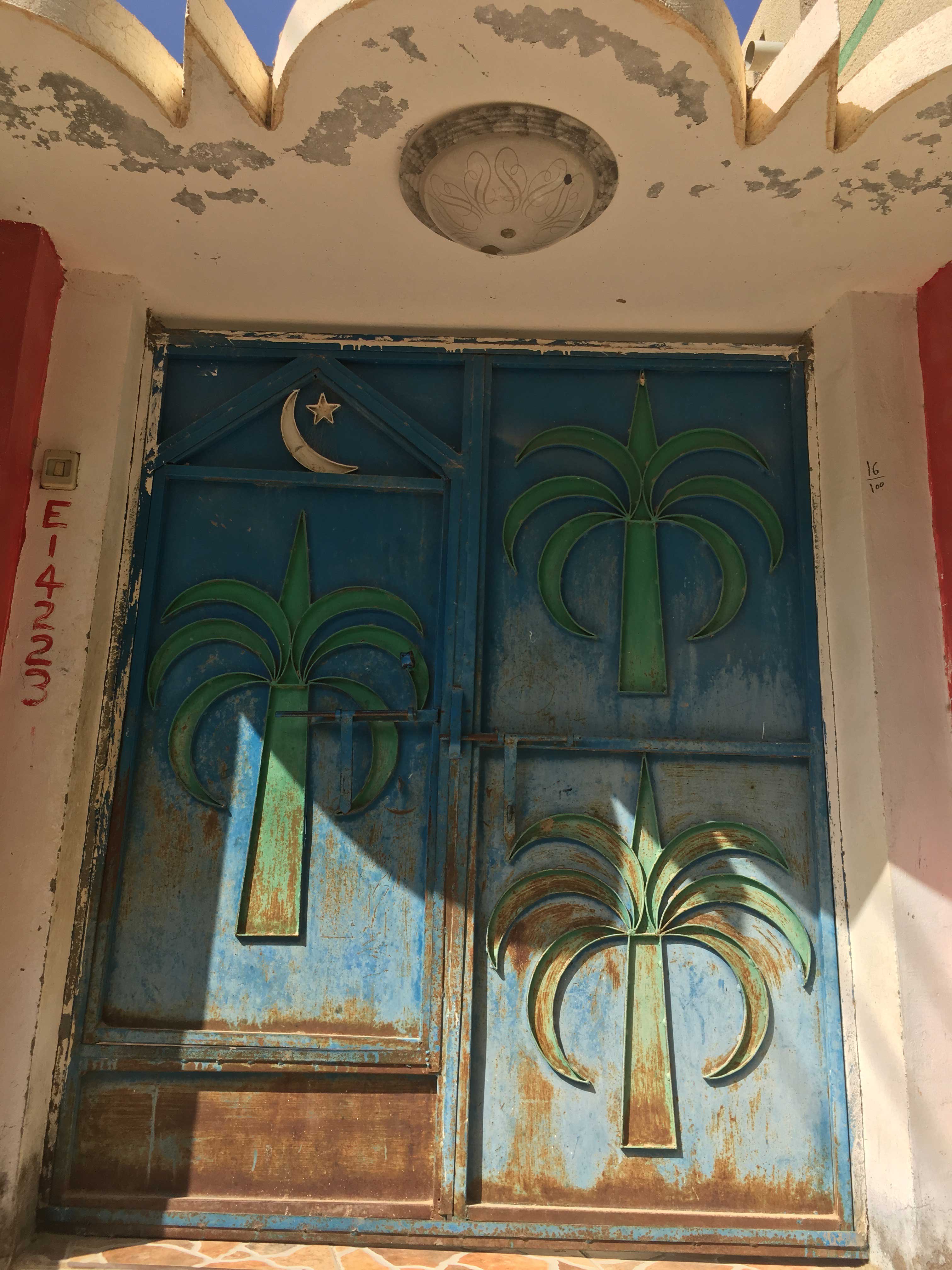

The average home is two stories high. The average public building is five to six stories tall. The dwellings that date from the pre-air conditioning era have outer stairways that lead to flat roofs where sleepers can catch what little cool breeze there is in the hot and humid four-to-five-month summer season. Many have lovely walled-in gardens. The gates into the gardens are often spectacular, whether they are the traditional wooden hand-carved designs from Zanzibar or newer, modern-looking metal ones. Both new and old are likely to boast understated calligraphic motifs that convey an image of modesty.

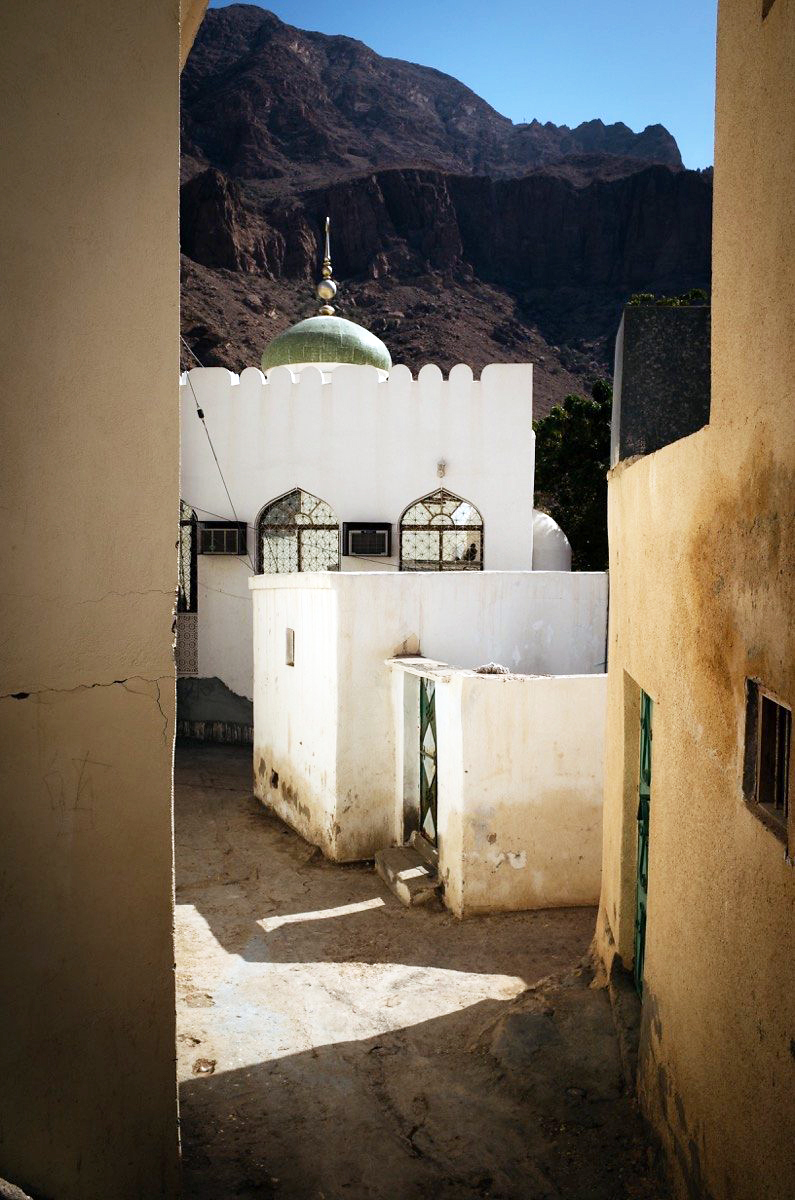

Old Muscat’s Al-Khor Mosque below the Mirani Fort, which overlooks the Sea of Oman.

The domes and minarets on the mosques are also striking. The royal color is lavender, but pale green, royal blue, peacock blue, and vibrant gold are also used. The dome and the minarets must always be the same color.

The flowers that bloom along the roadways are breathtaking, carefully chosen for color, and calming to the eye. Hundreds of thousands of petunias – lavender, white, pink, and purple – have been tenderly planted and are weeded and nurtured to form a mass of disciplined color. They often seem to bounce off the blueness of the sky and the café au lait of the desert. Every detail has been considered and executed beautifully.

Gorgeous planting in Muscat.

Oman is one of the cleanest countries in the world. When driving along the highway or side streets you can occasionally see a Vespa or small motorcycle with two large sacks. The driver retrieves litter – it’s his sole purpose. Oh and by the way, if your car is dirty in Muscat you will get a ticket.

Even the country’s signage is controlled; the water tanks atop many houses and buildings must be obscured from public view by the device of any of three approved, stylistically sensitive enclosures, all of which are white.

Men with khanjars (daggers) around their waists move in their dishdashas, the national dress for men, an ankle-length, collarless gown with long sleeves and a distinctive thin tassel, absent from all other Arab countries’ traditional robes, that dangles gracefully from the neckline.

The national emblem of Oman featuring the khanjar at the center.

The khanjar is more a symbol of male national identity than elegance although it is that, too. There are many other accessories, such as the mussar (a type of turban).

Men wear a khanjar and a buckler shield for formal dress.

In public most women wear an abaya, a modest black dress or cloak worn over the clothes, and the hijab, the typical Muslim hair covering. At home, the Omani woman sometimes wears a long dress with ankle-length pants and a leeso, or scarf, covering her hair and neck. Multitudes of lively colored and just as loosely fitting jalabiyyas are also worn at home.

Oman overlooks the Arabian Sea, the Sea of Oman, and the Arabian Gulf. It also overlooks the Strait of Hormuz, which links the Sea of Oman with the Arabian Gulf – it’s a gateway for all ships coming from the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea. Thirty percent of the world’s oil passes through this strait.

Oman’s first great asset is its insularity. It has natural boundaries that shelter it: mountains, deserts, and the sea. Yemen, to the south, has been mired in conflict for five years; across the Gulf of Oman are endlessly troubled Afghanistan and nuclear-enabled Pakistan. To the north of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf lies Iraq, entangled in war. For a speedboat it’s a short 35-mile stretch from the tip of Oman’s Musandam Peninsula across the strait to Iran. Oman’s insularity is buttressed by political neutrality – Oman’s diplomatic policy has been characterized as “friend to all, enemy to none.”

Oman’s leader is Sultan Qaboos, who assumed the throne in 1970 in a palace coup, replacing his father, Sultan Said bin Taymur, an isolationist so fearful of foreign influences that he even banned sunglasses. Private cars were illegal. During his reign Oman had three schools, one hospital, about six miles of paved roads, and no newspapers. Only royals were allowed to be educated. Needless to say, Sultan Qaboos inherited a severely underdeveloped society.

One of the many portraits of Sultan Qaboos.

The Sultan today presides over a transformed nation. When tumult gripped the region after the “Arab Spring,” Sultan Qaboos responded creatively. According to Al Monitor, the government “increased spending on social programs.” The Sultan “ordered the government to create 50,000 jobs and pay every job-seeker $386 each month.”

The Al Alam Palace in Muscat is the ceremonial palace of Sultan Qaboos. “Al Alam” means “The Flag” in Arabic. This delightful building made me think of Dr. Seuss.

Privately educated in the southern Omani city of Salalah before attending Sandhurst, the Sultan is progressive. His exceptional taste in all things aesthetic is evident in architecture and urban development.

In 46 years Sultan Qaboos has, almost singlehandedly, thoughtfully and cautiously guided his country on a path to modernity. Poll after poll show him to be the envy of many. He has the status of the most revered head of state among all of the 22 Arab countries’ leaders.

There are now more than 1,000 schools and 250 hospitals and medical centers in Oman. In this part of the world, where progress can be painfully slow and fundamentalism looks backward, Oman is one happy place.

Come with me now for some highlights of our two-week adventure to the Pearl of Arabia, Oman.

We first gathered in Washington, D.C. at the headquarters of the National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations. During our two-day pre-departure orientation the National Council treated us to a number of presentations on Omani history, economics, politics, and society by former U.S. ambassadors to the country as well as Omani diplomats and American specialists of the Arabian Gulf.

National Council on U.S.-Arab Relations offices in Washington, D.C.

The Council facilitates study visits to Arab countries for a broad range of American educators, students, elected officials, civic leaders, and other groups to expose the participants to a fuller picture of the Arab world than they might otherwise receive.

The delegation with which I traveled consisted of ten people, three being representatives of the National Council: Founder and CEO Dr. John Duke Anthony, Director of Research and Publications Mimi Kirk, and myself, Executive Vice President of the Huntsman Cancer Foundation and a Board Member of the Council.

Dr. John Duke Anthony, Ms. Mimi Kirk, and Ms. Paige Peterson.

One of our first stops was Muscat’s Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque. Opened in 2011, it is the main mosque in Oman and the only one open to non-Muslims. It is also one of the largest mosques in the Gulf, with room for 20,000 worshipers in two prayer halls. The overall style is stripped-down contemporary Islamic, clad in a thousand shades of beige marble.

Before entering The Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque, the four women in the delegation dressed respectfully in abayas and traditional head coverings.

The mosque’s spectacular chandelier is made of Swarovski crystal and gold-plated metalwork. It has 1,200 dimmable halogen lamps triggered by more than 36 switching circuits and weighs 8.5 tons. Its dimensions are 26 feet by 46 feet.

The carpet gracing the prayer hall is the world’s second largest handmade Persian rug, containing 1,700,000,000 knots and weighing 21 tons. The rug took four years, 600 female workers, and 12 million hours of work to complete.

The Bait Al Falaj Fort in Muscat was built in 1845 and now houses the Sultan’s Armed Forces Museum. The blue sky and hyper white buildings, with the date palms and gardens, are a beautiful sight. The museum, which includes both indoor and outdoor displays, has amassed an extensive collection of artifacts including uniforms, instruments, parachutes, antique cannons, early machine guns, boats, planes, and helicopters.

The Mutrah souq in Muscat is an absorbing labyrinth of narrow, perfume-laden alleyways packed with colorful little shops stacked high with tubs of frankincense, old silver khanjars, Bedouin jewelry, and other Omani paraphernalia.

The delegation met with many dignitaries and officials, including Dr. Adnan Al-Ansari, former Permanent Observer of the Gulf Cooperation Council to the United Nations (left) and representatives from the Public Authority for Investment Promotion and Export Development (right).

We flew to the Musandam Peninsula, the northernmost outpost of Oman, from Muscat.

The Portuguese built Khasab Castle, on the tip of the Musandam Peninsula, in the seventeenth century. Their goal of controlling the Strait of Hormuz was thwarted by the Omanis, who pushed them out mid-century. The distinctive curves of the castle’s tan walls meld beautifully with the blue sky and red, green, and white of the Omani flag. On the right: A majlis (sitting area) in the castle. The nooks in the walls held books and other cherished objects.

This type of house in the Musandam Peninsula allowed breezes to flow freely, helping residents to stay as cool as possible in the dry, hot climate.

From left: This village is perched in the mountains of the Musandam Peninsula with not a blade of grass to be found; Prehistoric carvings in Wadi Tawi in the peninsula sport ancient petroglyphs of camels, horses, and hunters; Donkeys, goats, and feral cats still roam freely everywhere.

From left: The goats are actually quite tame and very curious; Very wise fellow travelers watch as I retreat from this little house-turned-storage shed near Khasab. The stagnant air inside could have made a goat faint. In fact, there was a dead goat in residence. My gagging helped the delegation decide not to explore it further!

We sailed on a traditional Omani dhow. (The word dhow is used to describe all traditional wooden-hulled Arabian boats.) The earliest reported use of an Omani dhow was in the 700s. These trading vessels are still sailed today for trade, tourism, and fishing. In the evening, we anchored in a small cove that faced a village on a far shore. The call to prayer punctured the silent air during the night and at dawn. We slept on cushions, done in traditional Arab style, swam in the cool waters, and ate dinner and breakfast. A speedboat arrived with our delicious hot meals. It was a magical time as dolphins live in these waters; they playfully swam alongside us.

The Musandam Peninsula’s stunning fjords are often likened to those of Scandinavia, giving the area the nickname “The Norway of Arabia.” From our dhow, we could see the 33rd America’s Cup boats sailing in the Strait of Hormuz. Having been riveted by Jimmy Spithill and his Oracle win in the San Francisco Bay, it was wonderful to see them in the distance.

Every day, nearly a hundred speedboats loaded with goods leave Oman, cross the Strait of Hormuz, and arrive in Iranian harbors. Their cargo is everything from plasma televisions to cigarettes to flowers from Holland. The boats can do five or six crossings a day.

The village of Al-Hosn in Wadi Tiwi – our next stop after a flight back to Muscat and a drive down the coast – is full of spectacular scenes, such as these of immaculate white mosques shadowed by the mountains.

From left: Oman’s homes often feature metal doors with charming designs, such as this one from Al-Hosn; Portraits of the sultan can be seen everywhere, including on this cement column facing Wadi Tiwi; When the rains fall, the wadis fill and flood incredibly quickly, making spaces like this in Wadi Tiwi dangerous for campers.

Our next stop was a desert camp in the Wahiba Sands in the interior. On the way, we stopped by the oasis town of Hawia. Here, our guide, Badar Al Yazeedi of Panorama Travel, wearing a mussar, or traditional turban, educates us about the settlement. At the edge of the desert, we stopped again – this time to reduce the tire pressure in order to drive deep into a remote corner.

After arriving at our camp the delegation hiked to the skyline to watch the sun sink in the West. Everything is expansive in the desert.

A charming bed in a bedouin tent. Bedouin means “desert dwellers.”

From left: An elder tribesman walks to dinner in front of our permanent tents. He came to the camp for an event hosted by the Omani Association for Elderly Friends, which looks out for elderly men and organizes social events to ensure that they do not spend too much time alone; Relaxing and listening to music after dinner.

Early morning at the desert camp.

Our guide, Badar, at breakfast with an elderly gentleman who had traveled to the camp for the event.

From left: I took a leisurely camel ride further into the desert; Check out the eyelashes on the camel behind mine!

As we drove out of the desert we came upon a caravan of camels followed by a pickup truck driven by their herders. Adorable young camels followed their mothers.

We then traveled north to the ancient city of Nizwa. Nizwa Fort was built in the seventeenth century but stands on the remains of a ninth-century castle. An impressive example of Omani architecture, it is one of the largest and most visited of Oman’s monuments. On the right: The wooden perch, at the top of the fort, allowed its inhabitants to deter attacking enemies by pouring boiling date syrup on them.

Our guide, Badar, answers questions as we survey the vistas from Nizwa Fort. Climbing to the top of the fort provides a breathtaking 360-degree view of the surrounding countryside and Hajar Mountains – historically making a surprise attack virtually impossible.

People come from all the towns and villages around Nizwa to sell their products. From left: These men are selling their farm products in front of the fish market of Nizwa’s souq; Omani men at work making household products using the same methods they learned from their grandparents.

Silver necklaces made with imported gemstones and silver khanjars in the Nizwa souq. The gemstones are from Asia, Yemen, and Africa, as Oman has traded with them for centuries. Nizwa is famous for its silver jewelry. As Oman does not have any silver mines, most of this silver likely came from melting Maria Teresa Coins from the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

These are the ruins of a community near the town of Sinaw – not far from Nizwa. Such neighborhoods were common in Oman until about 40 years ago. Houses on the periphery would not have windows on the ground floor, and the width of their outside walls were doubled for security. Guards also stood at the entrances; as such, these can be thought of as early gated communities!

A staircase leads to the second floor and to the roof, where Omanis would sleep during the hot summer months. The roof was also used to wash and dry dates.

On our last day in Oman, an Omani family graciously hosted us for lunch in their home in the mountainous area of Jebel Akhdar. The family’s stand-alone building for entertaining was built to the side of the main house. Overlapping rugs, beautiful window treatment, a painted ceiling, and classic Arab seating adorn the room. Badar put down a sheet of plastic and placed the food on top. We were offered utensils, although Omanis usually eat with their hands. The food was fresh, traditional, and delicious. Here delegation members feast on chicken, rice, salad and, of course, lamb.

After lunch, we met and thanked the women of the family who had prepared our fantastic meal. The adorable little girl I’m hugging, who had joined us to eat, is six-year-old Maytha.

The delegation poses for a parting group shot.

Photos courtesy of Paige Peterson, Bonnie Carrender, and Mimi Kirk. Photo of Muscat corniche by Francisco Anzola, Flickr.

Videos courtesy of Paige Peterson.

A version of this photo essay appeared in the Saudi Gazette on April 30, 2016.

You must be logged in to post a comment.